Black metal-workers in Jamaica pioneered key industrial revolution innovation

7 July 2023

A key innovation of the industrial revolution, credited to Englishman Henry Cort, was in fact pioneered in Jamaica by Black metallurgists, the majority of whom were enslaved, according to a new study by UCL’s Dr Jenny Bulstrode (UCL Science & Technology Studies).

The innovation, widely known as the “Cort process” after the English financier-turned-ironmaster who took credit for it, enabled scrap and poor-quality iron to be converted into wrought iron on an industrial scale.

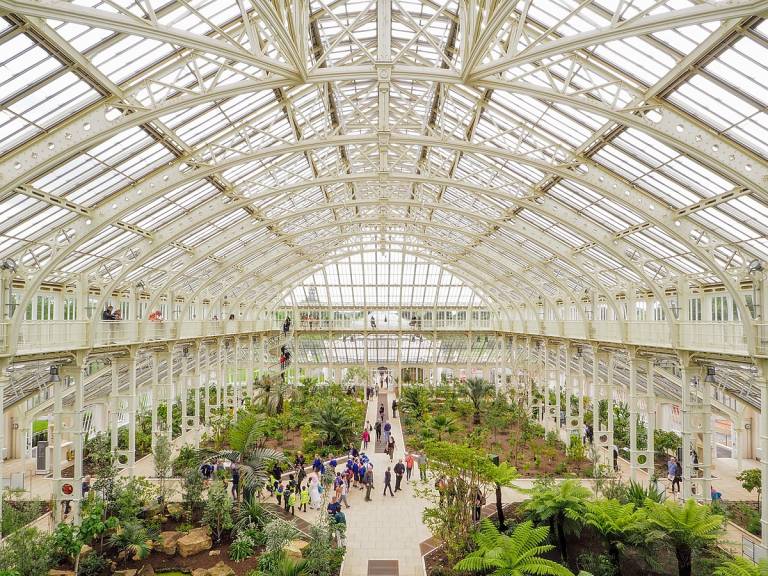

Profits from the innovation helped transform Britain into a global economic power, enabling British industries to manufacture and export everything from iron railways, iron ships, and iron engines to iron suspension bridges and iron factories. The method and its derivatives were even used to build “iron palaces” – famous structures such as Crystal Palace, Kew Gardens, and the archways at St Pancras International station.

The innovation was patented by Cort between 1783 and 1784, but in a new paper in the journal History and Technology, Dr Bulstrode shows how it was in use in a major iron works in Jamaica run by Black metallurgists several years before Cort’s patent. Many of these metal workers were enslaved people trafficked from West Africa and West Central Africa, home to some of the most important iron-working civilizations in world history.

The owner of the Jamaican iron works, a white enslaver called John Reeder, described himself as “quite ignorant of such a business” but how the Black metallurgists in his foundry were “perfect in every branch of the Iron Manufactory”, and, through their skill, could turn scrap and poor-quality metal into valuable wrought iron.

Dr Jenny Bulstrode (UCL Science & Technology Studies), the author of the research, said: “The myth of Henry Cort needs to be revised. The so-called Cort process – one of the most important innovations in the making of the modern world – was developed by highly skilled Black metallurgists, most of whom were enslaved, for their own purposes. Recognition of the debt the British industrial revolution owes to Black innovation is long overdue.”

The innovation combined two techniques: bundling scrap iron and heating it in a furnace that kept the metal separate from the heat source; and using grooved rollers, usually only found in sugar mills, instead of the smooth rollers conventionally used in European iron production. Bundled, heated and squeezed through the rollers in this way, the iron underwent a kind of mechanical alchemy that transformed it from worthless scrap into valuable metal. By 1781 the Jamaican iron works was making profit of £4,000 a year (equivalent to a relative annual income of £7.4 million in 2020 sterling).

While the Jamaican iron works turned spectacular annual profits, Henry Cort was facing bankruptcy. A financier from the age of 16, Cort took over the Portsmouth iron works of one of his clients in 1775 and laid out substantial sums to secure a contract to supply the Royal Navy’s iron work. He had hoped to make an easy profit, but soon found that he had contracted to trade the Navy’s old scrap iron for new, with no way of working up the old, rusted metal without making a loss.

Using shipping records and old newspapers, Dr Bulstrode’s research traces how Henry Cort learned of the Jamaican iron works from a visiting cousin, a West Indies ship’s master who regularly transported “prizes” – vessels, cargo and equipment seized through military action – from Jamaica to England.

In 1782, just a few months after Cort learned of the lucrative Jamaica foundry, the British government placed Jamaica under military law and ordered the iron works to be destroyed. The reason given in public was to prevent it falling into the hands of a rival power like France, Spain or Holland. In private, the military governor expressed the concern that if Black Jamaicans could convert scrap metal into cannon, then they could overthrow British colonial rule.

The foundry was razed to the ground, and the machinery and equipment from the works packed onto ships and transported to Portsmouth, where Henry Cort patented the innovation. The response in Britain was immediate. Politician John Baker Holroyd declared “our knowledge of the Iron trade seems hitherto to have been in its infancy” and, in direct reference to the loss of the American war and newly founded United States of America, described the so-called “Cort process” as being “more advantageous to Britain than Thirteen Colonies”.

Five years later, Cort was discovered to have embezzled £39,676 of Navy’ wages. In response, the British government confiscated the patents and made them public, enabling the widespread uptake of the innovation among British iron works.

Jamaican expert in development and reparations, Dr Sheray Warmington (Honorary, UCL Science & Technology Studies), said the findings were important for the present reparations movement. “This isn’t just about sugar, tobacco and cotton. It’s about Black intellect and innovation which was robbed from the colonies and used to build the wealth of the global north of today. Again and again we see histories of the industrial revolution present Black people as machines. This story shows Black intellect was the driver of innovation and prosperity. Black intellect, that was stolen. It’s time that theft and the countless other innovations that were stolen from colonised countries are recognised by their former colonisers as a key tenant of the reparations movement.”

Links

- The full paper in History and Technology

- Dr Jenny Bulstrode’s academic profile

- UCL Science & Technology Studies

- UCL Mathematical & Physical Sciences

- Media coverage

Image

- Top: Coalbrookdale by Night by Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg, 1801. The iron foundry used the Black Jamaican metallurgists' innovation. Science Museum No. 1952-452. Courtesy of The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

- Middle: The Temperate House at the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew in London. Credit: Karinsvad. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Media contact

Mark Greaves

E: m.greaves [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close