How gut bacteria change cancer drug activity

20 April 2017

The activity of cancer drugs changes depending on the types of microbes living in the gut, according to a UCL-led study into how nematode worms and their microbes process drugs and nutrients.

The discovery highlights the potential benefit of manipulating gut bacteria and diet to improve cancer treatment and the value of understanding why the effectiveness of drugs varies between individuals.

The study, published today in Cell and funded by Wellcome, the Royal Society and Medical Research Council, reports a new high-throughput screening method that unravels the complex relationship between a host organism, their gut microbes and drug action.

"The efficacy of colorectal cancer treatments varies greatly between patients. We wanted to know if this could be caused by microbes changing how the body processes the drugs. We've developed a rigorous system that could be used for pre-clinical screening of drug interactions in the context of host and microbe, or for designing bacteria for drug-delivery which could revolutionise treatments," explained study lead, Dr Filipe Cabreiro (UCL Biosciences).

"We forget that there are many organisms living in our bodies that interact with the food and drugs we ingest. Until now, probing the relationship between host, microbe and drug has proved difficult. Often microbes are studied in isolation, which isn't realistic, but using our in vivo method, we've had some striking insights into how drug activity can be bolstered or suppressed by gut microbes," said Dr Timothy Scott, first author (UCL Biosciences).

The team, involving researchers from UCL, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL, Germany), University of Helsinki and Birkbeck, University of London, developed a new three-way screen based on C. elegans. This worm is commonly used as a simple model for human metabolism due to its evolutionary similarity to humans and its comparable relationship with microbes.

They screened 55,000 conditions in C. elegans by varying bacterial genes as well as drug types and doses. The team then used computational analysis to map in great detail how the bacteria's genetics, dietary sources and chemical compounds affected the effectiveness of fluoropyrimidines, a common type of colorectal cancer drug.

Fluoropyrimidines act by stopping DNA being produced, which prevents cells from dividing in an uncontrolled fashion, a typical feature of cancer cells. They are commonly given in a pro-drug form, meaning that it needs to be broken down by the liver to become an active drug. Although fluoropyrimidines are a common cancer treatment, there is no universally accepted dose and genetics alone do not explain differences in patient responses to the drug.

The extensive screening in this study highlighted two distinct ways that bacteria change drug activity in worms. Firstly, some bacterial strains help to process the pro-drug into an active drug form, enhancing drug activity, and secondly, the bacteria influence the metabolic environment of the cell making it more prone to drug-induced cell death.

The team also found that co-therapies for cancer may limit treatment success if the host-microbe-drug interactions are not taken into account. For example, they found the anti-diabetic drug metformin reduces the efficacy of fluoropyrimidines in C. elegans by inhibiting the positive actions of bacteria.

"We've highlighted a critical missing component in our understanding of how drugs really work to treat disease. We plan on investigating this area further, as identifying which microbes are responsible for drug activity in humans, and their regulation by dietary supplements, could have a dramatic impact on cancer treatment outcome," Dr Cabreiro concluded.

Links

- Research paper in Cell

- Dr Filipe Cabreiro's academic profile

- Dr Timothy Scott's academic profile

- UCL Structural & Molecular Biology

- UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health

- UCL Computer Science

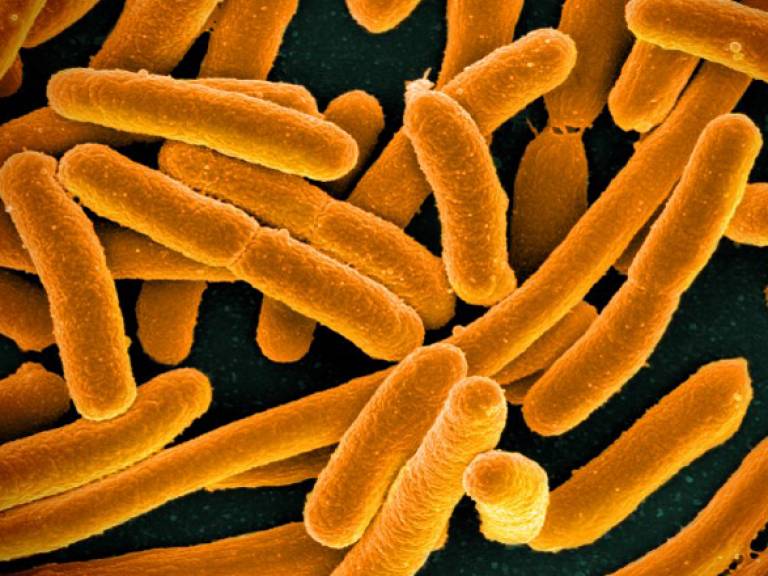

Image

- E. coli bacteria (Credit: NIH, Source: Flickr)

Media contact

Bex Caygill

Tel: +44 (0)20 3108 3846

Email: r.caygill [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close