Brain's map of space falls flat when it comes to altitude

8 August 2011

Animals' brains are only roughly aware of how high-up they are in space, meaning that in terms of altitude the brain's 'map' of space is surprisingly flat, according to new research.

In a study published online in Nature Neuroscience, scientists studied cells in or near a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which forms the brain's map of space, to see whether they were activated when rats climbed upwards.

The study, supported by the Wellcome Trust, looked at two types of cells known to be involved in the brain's representation of space: grid cells, which measure distance, and place cells, which indicate location. Scientists found that only place cells were sensitive to the animal moving upwards in altitude, and even then only weakly so.

Professor Kate Jeffery, lead author from UCL Psychology and Language Sciences, said: "The implication is that our internal sense of space is actually rather flat - we are very sensitive to where we are in horizontal space but only vaguely aware of how high we are.

"This finding is surprising and it has implications for situations in which people have to move freely in all three dimensions - divers, pilots and astronauts for example. It also raises the question - if our map of space is flat, then how do we navigate through complex environments so effectively?"

How the hippocampus makes its map of space is fairly well understood for flat environments, but the world is of course not flat - it has a richly varied topography, and a useful map therefore needs to work in all three dimensions. However, adding a third dimension to the two horizontal ones makes things very much more complicated for a map, and it is not clear how - or even if - the brain can encode this.

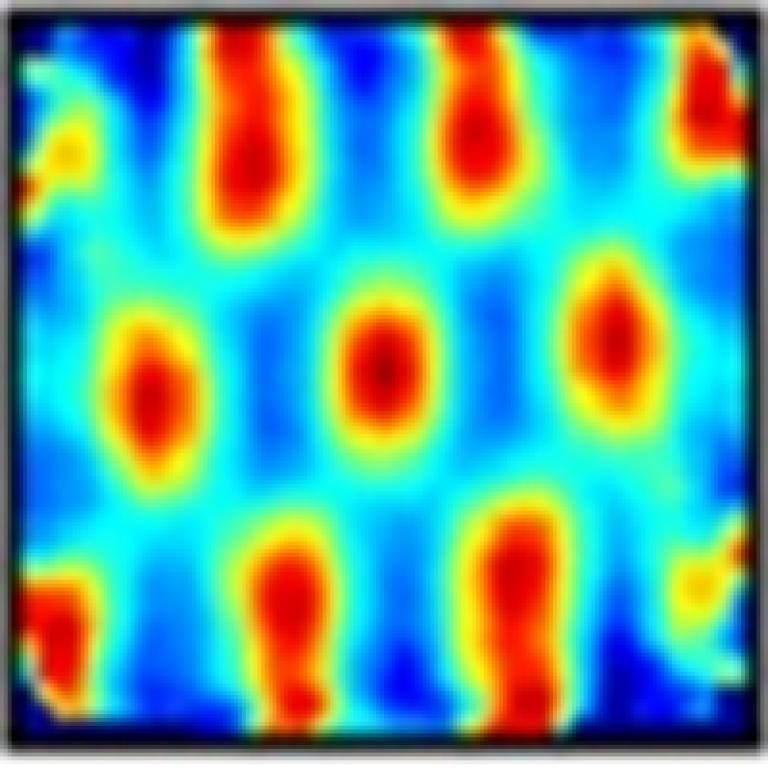

To begin to answer this question scientists looked at neurons known as grid cells, which become active periodically and at very regular distances as animals walk around, forming a grid-like structure of activity hot-spots. Previous work has found that grid cells are largely concerned with marking out distances.

In the study, rats walked not just on flat ground but also on pegs on a climbing wall, or else on a spiral staircase, so that the rats moved not only horizontally but also vertically. Interestingly, the grid cells still kept track of horizontal distance but did not measure out vertical distances. It seems as if grid cells do not "know" how high they are.

In the second part of the study scientists looked at another type of neurons known as place cells. Place cells, found in the hippocampus itself, produce single activity hotspots in the environment and seem to function to encode specific places. These neurons were only weakly sensitive to height too - but they did show some responsiveness, suggesting they received information about height from some other, possibly non-specific, source.

Professor Jeffery said: "It looks like the brain's knowledge of height in space is not as detailed as its information about horizontal distance, which is very specific. It's perhaps akin to knowing that you are "very high" versus "a little bit high" rather than knowing exact height."

Image: Firing pattern from a grid cell recorded on a flat surface. Credit: Kate Jeffery/UCL

Media contact: Clare Ryan

Links:

Close

Close