The Voyager programme is famous as having made the first detailed images of many outer Solar System bodies, including the moons of Jupiter, and the planet Neptune. Voyager 1 is also the most distant human-made object in the Universe, now on the brink of leaving the Solar System after almost 36 years in space.

Despite their age and, by modern standards, rudimentary

cameras, the Voyager missions sent back some remarkable images. The way these

are presented in modern publications usually involves some degree of computer

reprocessing of the original data, recovering detail that was not available at the time.

But that is not how the pictures initially looked when

beamed back to Earth.

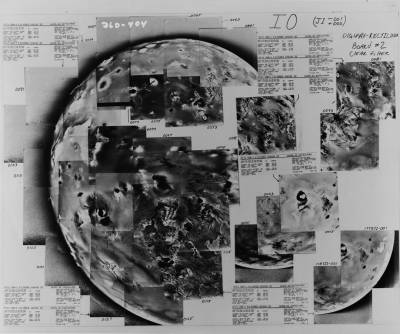

Io by Voyager 1, 1979

(click image to enlarge)

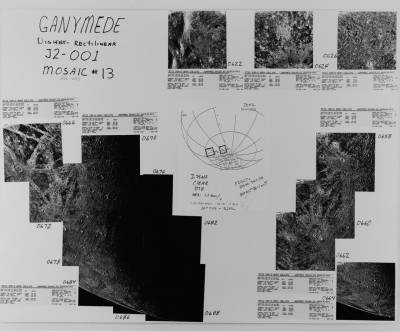

Ganymede by Voyager 2, 1979

(click image to enlarge)

Unlike modern space probes, which use CCD detectors (digital

devices similar to those in consumer digital cameras), the Voyager missions and

others prior to the 1980s used vidicons, a type of analogue detector closely

related to (analogue) TV cameras.

Both Voyager probes visited the Jovian system in 1979, before taking different paths through the outer reaches of the Solar System, studying the giant planet as well as making numerous images of its moons. Some of these moons are very large indeed.

Ganymede and Io are both larger than the Earth's Moon, and Ganymede is bigger even than the planet Mercury. The relatively narrow field of view, combined with the Voyager probes' close flybys meant that the photos had to be stitched together - which in the days before powerful computer graphics software meant printing them out and sticking them together by hand, like a giant jigsaw puzzle, interspersed with hand-written notes and computer printouts of technical information relating to the photographs.

The resulting pictures look nothing like anything that ever gets published today – but they are a charming reminder of how planetary science used to be done, within living memory.

Voyager’s mosaics of Io and Ganymede will be on public display during the Festival of the Planets at UCL.

Close

Close