Supercomputer simulations unlock space weather puzzle

14 May 2021

Scientists have long questioned why the bursts of hot gas from the Sun do not cool down as fast as expected, and now a UCL-led team of researchers have used a supercomputer to find out why.

The team will now compare their simulations with ‘real' data from the European Space Agency’s flagship Solar Orbiter mission, with the hope that it will confirm their predictions and provide a conclusive answer.

The solar wind is a stream of charged particles continuously shot out from the Sun into the solar system. These ejections greatly impact the conditions of our solar system and constantly hit the Earth. When the solar wind hits the Earth, it is almost 10 times hotter than expected, with a temperature of about 100,000 to 200,000 degrees Celsius. The outer atmosphere of the Sun, where the solar wind originates, is typically a million degrees C.

If the solar wind is particularly strong, it can cause problems to satellites, astronauts in space, mobile phones, transport and even electricity networks that power our homes.

To successfully forecast and prepare for such space weather events, a team of scientists are trying to solve the mysteries that space weather holds, including how the solar wind is heated and accelerated.

The team, with funding from the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) and the European Space Agency (ESA), ran and analysed simulations of the solar wind on a powerful supercomputer.

The simulations were carried out using the DiRAC High Performance Computing (HPC) facility’s Data Intensive at Leicester service, funded by STFC.

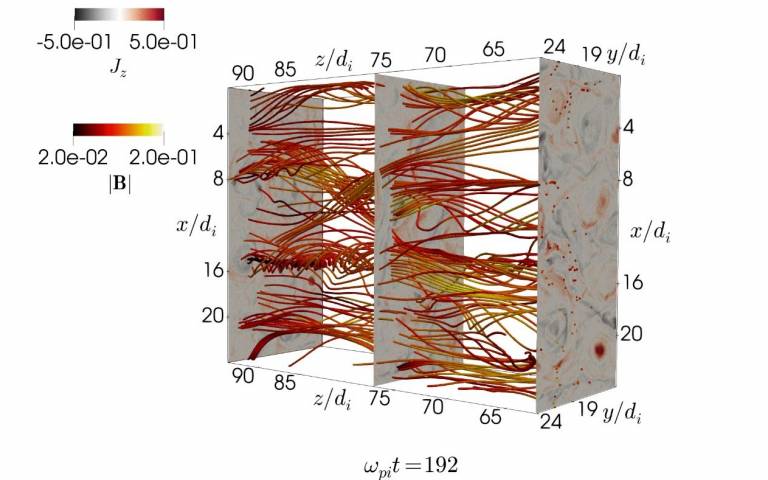

Using these simulations, the team deduced that the solar wind stays hot for longer because of small-scale magnetic reconnection that forms in the turbulence of the solar wind. This phenomenon occurs when two opposing magnetic field lines break and reconnect with each other, releasing huge amounts of energy. This is the same process that triggers large flares erupting from the Sun’s outer atmosphere.

Lead author and PhD student Jeffersson Agudelo (UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory) said: “Magnetic reconnection occurs almost spontaneously and all the time in the turbulent solar wind. This type of reconnection typically occurs across an area of several hundred kilometres – which is really tiny compared to the vast dimensions of space.

"Using the power of supercomputers, we have been able to approach this problem like never before. The magnetic reconnection events we observe in the simulation are so complicated and asymmetric, we are continuing our analysis of these events.”

To confirm their predictions, the team will compare their data with the data collected by ESA's Solar Orbiter mission, in which the UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory plays a leading role.

Co-author Dr Daniel Verscharen (UCL MSSL) said: “If we link our detailed simulation results with the cutting-edge observations from Solar Orbiter, we will hopefully make a major leap forward in our understanding of the solar wind.”

Professor Chris Owen (UCL MSSL) is Principal Investigator of Solar Orbiter’s Solar Wind Analyser, and co-author of the latest paper. Another UCL MSSL scientist, Dr David Long, is co-Principal Investigator of the spacecraft’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager.

Links

- Full paper in the Journal of Plasma Physics

- Dr Daniel Verscharen’s academic profile

- UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory

Image

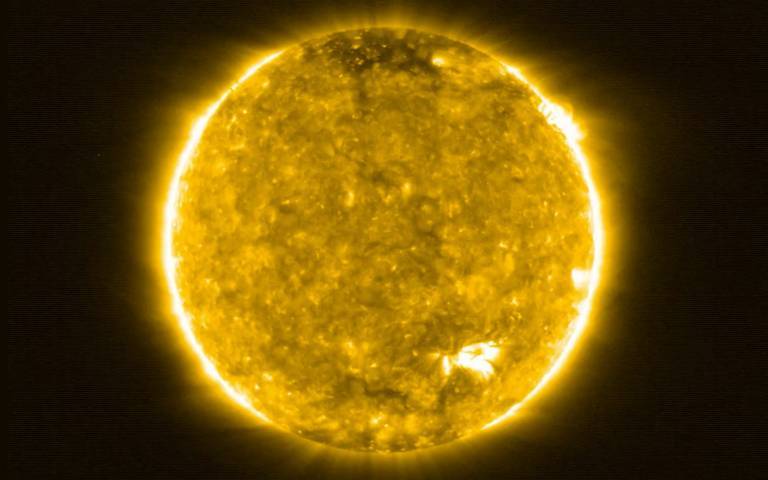

- Top: The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) on ESA’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft took this image on 30 May 2020. Dr David Long (UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory) is Co-Principal Investigator of the instrument. The image shows the Sun’s appearance at a wavelength of 17 nanometers, which is in the extreme ultraviolet region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Images at this wavelength reveal the upper atmosphere of the Sun, the corona, with a temperature of around 1 million degrees. EUI takes full disk images using the Full Sun Imager (FSI) telescope. The colour on this image has been artificially added because the original wavelength detected by the instrument is invisible to the human eye. Credit: Solar Orbiter/EUI Team (ESA & NASA); CSL, IAS, MPS, PMOD/WRC, ROB, UCL MSSL.

- Middle: Credit: Agudelo et al./ Journal of Plasma Physics

Media contact

Mark Greaves

T: +44 (0)7990 675947

E: m.greaves [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close