S2 Ep6: Mission to Mars

MORE ON THE STORIES

CREDITS

- uEffects Camera Focusing and Shutter

- Florianreichelt Soft Wind

- 4ntony Robotic Arm

- Eschwabe3 Ship Radar

- dheming Breaking_Ice_01

- ShadowReaper2814 Boiling water

- CaganCelik Highflow River

- klankbeeld forest summer Roond 022 200619_0186

- straget The rain falls against the parasol

TRANSCRIPT

#MadeAtUCL episode 6: Mission to Mars

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

mars, life, astronauts, rover, ucl, astrobiology, space, universe, planets, earth, mission, rosalind, people, surface, spacecraft, understand, parachute, called, solar system, bit

SPEAKERS

Professor Andrew Coates, Professor Ian Crawford, Dr Iya Whiteley, Cassidy Martin

Cassidy 00:03

Hello, I'm Cassidy and welcome to the sixth episode of series to have made at UCL the podcast. This podcast explores the world of UCL through the groundbreaking research and vital community work conducted by our staff and students.

Cassidy 00:22

There's this line in the movie Contact that I always think about when it comes to the idea of whether life exists on other planets: "The universe is a pretty big place, if it's just us, seems like an awful waste of space." It's so true! There's got to be something out there, right? Well, when it comes to the possibility of finding signs of life, scientists have set their sights on one of our closest planets,

Professor Andrew Coates 00:49

Mars, the red planet

Cassidy 00:51

a planet that although basically uninhabitable now...

Dr Iya Whiteley 00:55

I think it's a very silent place

Cassidy 00:57

was many, many, many years ago, habitable and even resembled our own planet.

Professor Ian Crawford 01:04

I think why Mars is important is that it is the one place, I think, that we can explore that in the near future could give us an insight into how common life is in the universe.

Cassidy 01:16

This means that there is a strong possibility that at one point or another, there was life on Mars. To help us understand how scientists look for signs of extraterrestrial life, collect data and travel to Mars, I sat down with some of UCL's top specialists in space science.

[intriguing space music]

Cassidy 01:37

Our first guest is Andrew Coates, a Professor of Physics at UCL's Mullard Space Science Laboratory and the Deputy Director in Charge of Solar Systems. His research is in

Professor Andrew Coates 01:50

planetary science, what makes us so special really comparing the other planets to the earth and trying to understand our place in the universe.

Cassidy 01:58

And his current projects involve

Professor Andrew Coates 02:00

missions to Mars. So we have the Rosalind Franklin rover going next year. So I'm Principal Investigator of the Pancam instrument on the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Rover, which gets to Mars in 2023.

Cassidy 02:13

And this Rover's mission is really exciting, because it's the first of its kind, but we'll get into what makes it different and why that's so exciting later on. For now, I'm going to let Andrew set the scene for you both now and way back when

Professor Andrew Coates 02:30

It's a really different environment. So, you have these enormous geological features on Mars - Valles Marineris, which is much bigger than the Grand Canyon; you have Olympus Mons the biggest volcano in the solar system, it's three times the height of Mount Everest... And of course, what we're going to be doing is landing on the surface of this amazing object, which might 3.8 billion years ago have actually harbored life at about the same time that life was starting on Earth. And so we think that the Mars environment at that time is very different from the way it looks, now. You know, the way it looks now is this sort of red dry desert type place with rocks and boulders on the surface but not much going on. But 3.8 billion years ago, we think it probably looked a bit more like Earth, so with water on the surface, rivers, clouds in the sky. If you were on the surface, you'd have a blue sky because of the scattering of light just the way we have it on earth and so a much more earth like environment where life could have happened. So to me Mars, just looking out at the night sky just thinking wow, you know, we're going there with a mission, we're sending a rover to Mars to look for signs of life there. I just feel very connected with it.

[uplifting music]

Cassidy 03:40

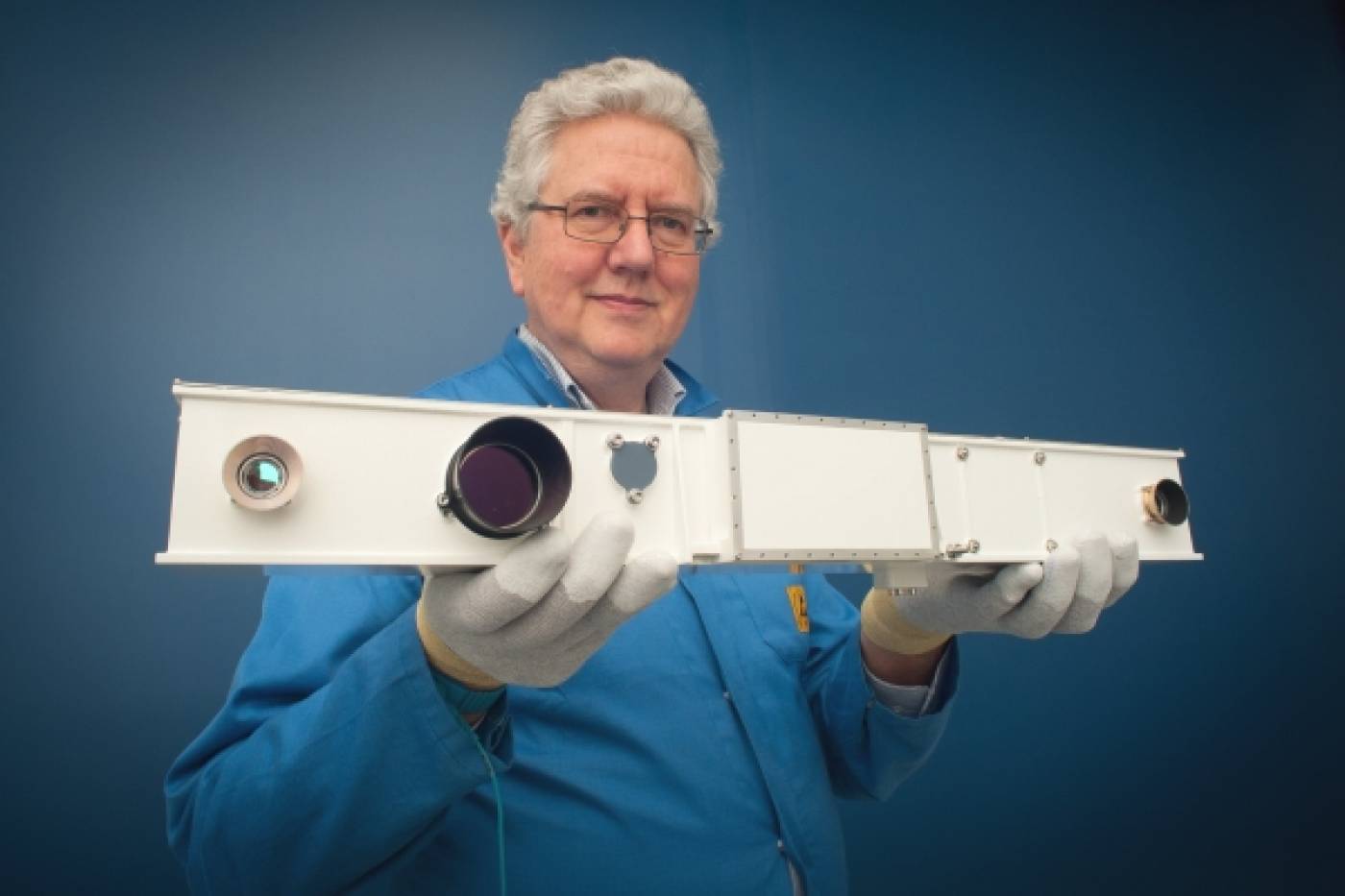

Now Andrew's particular part in the making of the Rover has been centered around creating the sophisticated 360 degree camera called the Pancam that will act as the mission's eyes.

Cassidy 03:52

[to Andrew] You brought your Pancam, would you mind describing it to our listeners, I know they'll be able to see a picture of it if they look on our website [laughing].

Professor Andrew Coates 04:04

So basically, the Pancam is a white box which sits at the top of the rover mast. It's about 60 centimeters long. At each end, we have an aperture behind which we have each of those wide angle cameras. In front of that we have a filter wheel with 11 filter petitions on it with different colors. So with that we can do geology and atmospheric science, but also we have R, G and B so we can get color. So we can take color pictures on the surface of Mars [camera lens shutting]. So, this is two meters above the surface of Mars, so it's a little bit taller than a person. We also have a high resolution camera. So the aperture for that is a little bit inboard of the right wide angle camera. The light comes in for that, there's a mirror inside, then there's a focusing mechanism [camera focusing sound] and a image plane. So with that, it's sort of behaving a little bit like a telescope to look very closely at particular rocks to look at features in the rocks to try and understand rock texture. So it's a little bulge on the front of this. This is the DCDC converter. So that gives us power. So the rover gives us power from a cable coming up the mast. And so this little bulge converts that into the power that we need for the instrument. There's another thing on the front, and this is called a HEPA filter. So this means that the the air inside [wind sounds] or the environment inside can't get out and what's outside can't get in. So this helps with what's called "planetary protection" to make sure that we don't take life to Mars and measure that, you know, that's the last thing we want to do - we want to see indigenous life on Mars. That's what we're trying to look for. So we have to be very careful. So that describes the actual optical bench. So this, we all made it at our lab, the Mullard Space Science Lab, which is 35 miles out of London. So there's another part of Pancam, which is the so called "small items". So this sits down actually on one of the solar panels, so below the optical bench on the Rover. So we have a calibration target with different colored bits of stained glass. We also have fiducial markers to get shapes right. We even have a little Rover inspection mirror [robot sounds] so we can look underneath the rover and see if there's any rocks underneath there as well. So that, sort of, describes roughly what it is and just thinking about a box like this and to think how much technology we've packed into this. It's a really complex camera system and the best scientific camera system to be sent to Mars yet.

Cassidy 06:19

And this complex camera system is a vital part of this Rover's first of its kind mission.

Professor Andrew Coates 06:26

The really new thing about this mission is drilling underneath the surface up to two meters for the first time. So that gets below where ultraviolet can get through Mars's thin atmosphere. And then also you need to drill deep to get below radiation from space. So galactic cosmic rays, and solar energetic particles, all of which can interfere with biomarkers, and the complex organic chemistry involved in life. And so you really need to be able to drill deep to do this. We had a UCL PhD student, a few years ago, who did some calculations about radiation environment underneath the surface of Mars and about whether life could survive or not. And he came up with, yes, a metre and a half is what you really need to do, drilling below a meter and a half to get underneath where the radiation can be a problem. So that's why the mission is doing what it's doing.

Cassidy 07:15

It's amazing that a student was able to influence a key part of a mission to Mars. And that that students calculations could lead to finding evidence of life right underneath the surface. This mission could involve the unveiling of one of life's biggest discoveries. But of course, in order to be able to make those all important drills that would lead to those discoveries, the Rosalind Rover is going to have to go on quite the harrowing trip.

Cassidy 07:43

Could you talk about the journey that Rosalind will be going on?

Professor Andrew Coates 07:47

Sure, well, you have the chance to launch to Mars every two years or so, just over two years, because of the way the planets line up - because Mars is year is longer than ours. So Rosalind is gonna be launched in September next year. So the first bit of the journey, of course, is the visible bit you see of the launch the amazing rocket going off, it's a Proton rocket, which we're going to be using from Kazakhstan. So little Rosalind is sort of all folded up in the capsule at the front of the rocket inside the carrier module, which actually takes it to Mars. So it launches up through the atmosphere goes into Earth orbit, and then the last stage fires for a second time to take it out of Earth orbit and take it on the way to Mars. So it goes around the solar system, travels over half a billion kilometers to actually get it to Mars around an arc, which takes it directly to Mars, and then it's going to enter into the atmosphere. It has a heat shield, which will stop it burning up in the upper reaches of the Martian atmosphere. Although Mars's atmosphere is thin, it's less than 1% of the Earth's atmospheric pressure, it's still thick enough to burn a spacecraft up as it approaches, and so it has heat tiles on the outer part of the shell on the outside of the module, which is eventually going to take it into the atmosphere. And then there's a couple of parachutes which come out to slow it down, and eventually, slowly enough that the spacecraft, the descent module comes out of the back shell with a parachute as well. And then that has retro rockets to stop it, eventually hitting the surface too hard. So then Rosalind is still folded up on the top of the Kazachok Landing Platform. So then she unfurls the solar panels to get power, and then the mast comes up, that's the mast with her eyes, and those are our eyes! And then there are also navigation cameras as well, which will help her to navigate around.

Cassidy 09:36

And then, it's coming back to the earth. Is that right?

Professor Andrew Coates 09:39

So Rosalind Franklin, she will be staying on Mars. So at the end of her mission, about seven months, we hope, of course for an extended mission. If the rover is still working, then there's a chance of keeping going: the Opportunity Rover which was on Mars kept going for 17 years, you know, there is no problem. If you can if you can successfully get to the surface and if the battery survive and that you know, if it's well enough designed, it should be possible to to survive quite a long time, hopefully have an extended mission and do some more science. So we'll squeeze as much science as we can out of it. And the samples, which it is collecting will be put in metal tubes eventually to be picked up by another Rover called the Sample Fetch Rover. So those samples will be brought back to Earth, but it's only for samples, it's not the Rover itself.

Cassidy 10:23

So it seems that if they do find anything, it's gonna be a while until they'll be able to see it up close and personal and truly analyze their findings. It's all a big, long process. Andrew and the rest of the team have spent years working on this rover that will complete the first part of this very important mission, and Andrew couldn't be prouder.

Professor Andrew Coates 10:46

In 2019 when we delivered it in May, it was quite a moment to be... to actually see the thing going off in the car and sort of be with the team. Such a proud moment to have come up with a concept, developed it over years. But a big team effort and to have the team together to do that, it was great. And now the next generation, you know, the PhD students working with us now are going to be actually working on the data. So they're so excited to handle these images, to be able to do some science and get some papers and theses out of this. So it's gonna be a great source of information for future students and postdocs.

Cassidy 11:26

Be sure to keep a lookout for the launching of the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Rover, set to take place September 20th 2022, with a landing on June 10th 2023. To find out more about this mission and others by the European Space Agency visit esa.int.

[quiet, contemplative music]

Cassidy 11:48

To understand the kinds of life that Rosalind Franklin could find on Mars and what that would mean for us. I spoke to Ian Crawford. He's a professor of Planetary Science and Astrobiology at Birkbeck College as well as an Honorary Research Fellow in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at UCL.

[radar searching sounds]

Cassidy 12:11

[to Ian] I know that you study Astrobiology, and I actually never heard of Astrobiology before preparing for this interview. Could you tell our listeners in your own words, what astrobiology is?

Professor Ian Crawford 12:27

Astrobiology is the name of this new science, which is a basically an attempt to search for life elsewhere in the universe. But it's very interdisciplinary, so it brings in aspects of Astronomy, and Geology and Planetary Science and Life Sciences all together in an attempt to try and find out whether there's life elsewhere in the universe.

Cassidy 12:49

It's, it's really, it's really fascinating, because I always think of the idea of studying life elsewhere, but I've never heard the name for it, I guess, and so now I know what it is. So when you're searching for life in the universe, what are some of the necessary elements that you are looking for that indicate the possibility that life does exist there?

Professor Ian Crawford 13:10

Firstly, we need to understand the history of life on Earth. So currently, the Earth is the only known planet in the universe which has life upon it. So understanding why the earth has life upon it is quite central to trying to find out where else we should be exploring in the universe to find other planets on which life might exist. So that's part of Astrobiology, understanding the history and evolution of life on Earth. But then, of course, the main theme is to try and find life elsewhere. And there are several different aspects to that. One is searching for life elsewhere in our own solar system, so planet Mars, for example, but also some of the moons of the outer planets in our solar system, places like Europa and Enceladus and Titan. These also may contain habitable environments, but we just don't know whether they're inhabited or not. And then there are planets around other stars. So one of the most exciting things that's happened in astronomy, in the last 20 years, is a discovery that planets are really common in the universe. Most stars have planets. So this means there's an awful lot of planets out there, and potentially they might be inhabited as well. But of course, all of these searches require different tools. Understanding the history of life on Earth is Geology and Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology. Searching for life on Mars requires space probes, like the Perseverance Rover that's currently on Mars, and searching for life around planets on other stars requires big space telescopes, I mean, that falls within the domain of the astronomers. So Astrobiology integrates all of these different aspects looking for life in the universe in many different places.

Cassidy 14:49

In your research, you've studied these like extreme environments that are kind of comparative with what you imagine those climates to be on Mars. So either past or current and Mars or other planets. Can you give us an example of one of the areas you studied and what you learned from your research there?

Professor Ian Crawford 15:10

Yes, so one of the things we've done at Birkbeck and with colleagues at UCL is trying to find... they're called analog sites, places on the earth that are relatively accessible, but which in some ways, maybe analogous to conditions on other planets, and particularly Mars, and particularly ancient Mars. So we've done some work in Iceland, in collaboration, mostly with Claire cousins, who was at one time a PhD student at UCL, but is now a lecturer at St. Andrews. And this work involves going to places in Iceland, where you have volcanoes, active volcanism, but you also have a lot of ice. The Vatnajökull Ice Cap, for example, has these volcanoes underneath it. So you've got environments where volcanic heat is interacting with glacial ice, so it's generally quite cold environment under this ice sheet. But where the volcanoes are underneath it, the ice melts, and you have these boiling, very hot boiling ponds of water [ice creaking and braking, boiling water]. So these are very hot. And microorganisms do live there, so called thermophiles, which enjoy living in very hot water. But our rationale there is that these kinds of environments where you've had volcanisms interacting with ice, I mean, these must have happened on Mars, there's no escaping the fact that they... such environments have existed on Mars in the past. And so the question is, maybe they're analogous and by learning what kind of microorganisms live in such places on the earth, this would provide insights into what kind of organisms might have existed on Mars, presumably, in the past. And that's the basis of that research.

Cassidy 16:51

If we are able to find life somewhere else, what do you think that will mean for us here on Earth?

Professor Ian Crawford 16:59

I think, the first thing that will be important if we were to discover life on Mars, or evidence of past life on Mars, that's a fantastic, I mean a key discovery, right? That will be somebody's Nobel Prize just there. But then there's a next question. And the next question is, does it represent an independent origin of life? Or is it just the same life that's just been splashed around the solar system as planets have been exchanging meteorites and with the meteorites living cells. We don't know how life originates from non life, it's a major unsolved scientific problem. And we don't know whether that's common or not. If it turns out that life originated on Mars independently, suppose we get to Mars, and we find evidence for life, and we discover that it's completely different from Earth life, like it has a different genetic code or different basic biochemistry, it's so different, that it can't be related to our life, it's an independent origin of life, then that's the most important result of all because that shows that on two planets next to each other, nature has managed to make living things independently, and therefore probably nature can... if it does on two planets in the same solar system, it's probably doing that on all the planets in the universe, and life is probably really, really common. This is really important, because that will change our whole view of the of the universe, I think. So that's the kind of key scientific interest, from a wider societal perspective, then, I like to think it would make a big difference for us to, you know, for humanity to know whether we're alone in the universe or not. I mean, we could not, at least in my view, we couldn't justify humans colonizing Mars if Mars has life of its own. I mean, that would be an unconscionable thing to do, at least in my view, although I know not not everyone agrees. So we need to find out whether Mars has any life of its own before we start thinking about colonizing Mars. And so astrobiology is the science which will help us get these answers.

Cassidy 19:10

Ian brought up two really interesting points here that I had never thought about before. First, if we find life on Mars, which is a big deal in and of itself, because it tells us life exists outside of this planet. It could also tell us if life can originate independently. And if so, that means there is a huge possibility that there are all kinds of life forms that can be found throughout the universe. That's huge! And second, if there is currently life on Mars, or any other planet that we explore in the future, for that matter, we need to leave them be. Because us visiting them could have dire consequences for those life forms' existence.

[slightly mysterious and awe inspiring music]

Cassidy 19:57

Of course, I couldn't let him leave without asking him the question that everyone always has in the back of their mind.

Cassidy 20:03

[to Ian] Just out of curiosity, do you do you think there are other forms of life similar to us in like a distant galaxy somewhere? And why or why not?

Professor Ian Crawford 20:14

Well, I've learned to not answer that question. I think we have to address this scientifically. We just have to get out into the universe and look for it. So I've dodged your question and I really, I think it's because I don't really have a view. 10 or 20 years ago, I would have guessed. My guess who would have been microorganisms probably are quite common in the universe. But large, complicated multi celled organisms, I would have argued, probably very rare in the universe. And my rationale there, and this is this is still... I think this rationale is still correct is that, if you look at the history of life on Earth, it did take an awfully long time for multi celled organisms to evolve, whereas microbes seem to have been present almost as soon as the earth became habitable, perhaps 4,000 million years ago, we've got evidence for life on Earth, but they were microbes. And I still think that, but where I've become a little bit more cautious recently, is the idea that even single celled life might be quite common in the universe. I'm much less sure of that now. The more biology I learn, and so this is a benefit of Astrobiology, right, because it forces me as an astronomer, to learn a lot of biology, and the more biology I have learned, the more impressed I am by the sheer complexity of even things that are said to be simple, like microbes, because they are not simple - the complexity of them is astounding. So I now feel that speculating about how common life is in the universe isn't going to get us very far, what we have to do is get out into the universe and look for it.

[radar searching sounds]

Cassidy 22:04

In my conversation with and we talked about the ethical implications of finding life on Mars, and what that could mean for sending humans there. The idea of sending people to Mars feels like science fiction, but it could happen in our lifetime. I spoke to Dr. Iya Whitley, a space psychologist and director for the Center of Space Medicine in the UCL Department of Space and Climate Physics, about what the journey would look like and what kind of qualities you would need to survive it.

Cassidy 22:34

[to Iya] So you've recently been involved with the preparation process for future astronauts on the mission to Mars, from what I understand, have future astronauts to Mars already been recruited and started training or has this not happened yet?

Dr Iya Whiteley 22:49

There's not a mission plan yet. You know, the team will not be selected until we have the technology. So for the Mars mission, the people that we have, currently in Astronaut Corps around the world, maybe some of them will go to Mars, but it is not certain. Certainly, we are a long way away from selecting a specific team to go to Mars. I have worked on projects that are looking to consider the type of challenges the crew will have on long duration missions to the moon and Mars. And this was the first project in the UK after Margaret Thatcher cancelled human spaceflight engagement from the UK, or the European Space Agency.

Cassidy 23:42

Even though there's not a mission to Mars, yet, there is a lot to consider in preparation for the possibility of there being one. And anyone who is being considered for a mission to Mars, or any space travel for that matter, will have to undergo a number of challenges.

Dr Iya Whiteley 23:58

There's 36 categories of challenges that they will come across that were systematically prepared. And that is like a map or journey that we all researchers, everybody who is preparing for human spaceflight mission, and particularly for training and the journey to and from Mars, we're likely to come across the majority of those challenges listed there. And there is over 2000 individual situations that are only created by two factors. So for example, the interior of the spacecraft is deteriorating, and someone didn't have enough sleep. Let's say like these two factors, and here you can see that something could happen, right? So for example, someone touched something and they're really exhausted and the handle broke. You know, how will they handle that? If you're in a good mood, and kind of have a deep, calm sense of well being you're robably going to say, "Okay, well, yeah, I'll just see how I can fix that". But on the other hand, if someone is just at the end of their tether at that point, then they may take it in a very different way. And then everything that day won't go right. We're all human, right? So astronauts are not protected from that. So we've looked at the situations like that, and made sure that we can be as elaborate as possible. So we can train, prepare scenarios, create situations on the problem, discuss, elaborate on what kind of tools and techniques they need to prepare and to overcome.

Cassidy 25:43

I asked Iya if they look for a particular kind of person, someone who they think will do well on these sorts of scenarios. Or if astronauts acquire the right kind of temperament through training.

Dr Iya Whiteley 25:55

You would select for that, you would look for people who are natural leaders, and those that can easily transform into being a follower, if required, if somebody knows better. So there is always this balance between leadership and followership. And it is important to recognize and give someone the space to lead, even though you may be in a position higher than them, but they might be more aware and their opinion matters -everybody's opinion matters, because none of us can see, sort of, the whole situation at all times. And some people would have a much better sense in a particular area, so everybody's listened to, and then everybody's opinion accounted for and then the decisions are made.

Cassidy 26:50

Is there any other skills that people have to use, any other attributes that you're kind of looking for in people besides just being cooperative and having this listening to each other's ideas, what other types of things are you looking for when you're recruiting people?

Dr Iya Whiteley 27:06

Generally these people would be quick thinking, problem solving, they would be able to work with whatever they have around them, because the resources are limited. So they will have to adapt, they will have to make sure that everything around them is in order, so that they have to be very much situationally aware on what is happening, they can't miss out the details, they have to be very detailed oriented, but also be able to zoom out and see the global picture, also not to get bogged down into detail and forget about the overall mission. So this ability to consider on how the situation will evolve, consider several scenarios, be quick on your feet, be very good with your hands, because they have to do from repairing a very complex software, for example, to cleaning the toilet, to piloting the spacecraft, to running experiments, to understanding about orbital dynamics, to be able to provide public engagement. So all of the skills have to be in that one person because they are not just the person who is highly skilled, possibly even rocket scientist, but they also have to be very much social, very, very good social skills. And as well as be able to engage and speak the language of anyone who will be speaking with them from child to a professional.

Cassidy 28:38

Oh man, there's so much to consider and think of and look for. If a child was like, I want to be an astronaut, what would you tell them to do? Like what kind of training could they do to prepare and and be the, I guess, ideal recruitment? [laughing]

Dr Iya Whiteley 28:54

I would suggest that they pursue what they like and just investigate all the details. Look into all the questions they have. Reach out to every adult that they can think of that might have that knowledge. Learn how to do research, make your own rockets, if they're into rockets, or if they want to be a medical doctor in space, then study that and just love your job. Love what you do. Be kind, be considerate of others, and keep physically fit. Make sure you've got a balance between your study and health, which is very important and every astronaut very much spends considerable amount of time keeping fit, and mentally well. They have several hobbies, astronauts, a lot of them are also good artists. So they will either play an instrument, some astronauts draw like Leonov, the Cosmonaut Leonov, who was first to walk in space, he was considering himself firstly an artist and then a cosmonaut.

Cassidy 30:01

That's interesting, I've never... I never thought about artistry entwined with being an astronaut. Why do you think that is, is that like a sensitivity thing?

Dr Iya Whiteley 30:09

I see this as they're multi modal, sort of multi skilled. And in order to problem solve, you need to be versed in several knowledge bases? Because the more you know, the better you're able to pull various skills and various know how. You might be good at knitting, for example, and sewing, and the space suits are sewed, right? Some of the elements are individually made, and it's handcraft. And, similarly, all astronauts and cosmonauts that I know, they're really handy around the house, they know how to repair things, they will likely play an instrument like a guitar. I know people who play keyboards, and there is a guitar on ISS.

Cassidy 30:52

Now you also kind of have a plethora of outside hobbies, from what I understand. You fly, scuba dive, I think you've done skydiving and stuff as well. Do you think that's also helped with you, with your research and what you do with training and recruitment?

Dr Iya Whiteley 31:11

Definitely. I mean, that was my interest. I was interested how people make decisions in a split of a second or a moment when the situation changes very rapidly. What goes through people's mind, how do you adapt in a different environment that we're not meant to be or born to operate in. And so that was my interest, I wanted to know how people deal with fear, and we would climb into the aircraft and the door would be open, and you'd be sitting by the door, you know, although you have a parachute behind you, the door is open, and the parachute won't open if you fall out until you've got several 1000 [feet] below you. And that's quite an interesting sensation, to be aware, to be alert, your senses sharpen up. You know what safety tips you need to follow, there's a safety protocol, there's a procedure to make sure your parachute is packed well, you didn't distract yourself because that's what your life depends on.

Cassidy 32:12

In the way that Iya was describing her hobbies and interests, plus her own vast understanding of what it takes to be an astronaut, and it almost seemed to me like she would be the perfect candidate to go into space. And as I soon discovered, she had considered being an astronaut herself and thought about possibly making the journey to Mars one day. She even had the most brilliant idea about what to bring to the Red Planet.

Dr Iya Whiteley 32:39

Well I was interested to become a pilot and to go to space. As I was doing the research for a long time it seemed and considering the type of challenges the crew will have, on the journey to Mars and on Mars, I felt like I lived there for a bit. It is like being in some sort of suspended animation almost. If you're really thinking of being on Mars, I would want to think that it's a very big beach, that the sea is very near or the ocean, but I just can't see it. Because I love the ocean. I would certainly bring all the sounds with me if I am to go. I would bring the sound of rain I would bring the sound of the forests, the river, maybe let the Mars listen to the sounds with me, to hear the Earth. I would let Mars here the Earth. Because I'm sure that there will be moments where you miss those sounds, well I know about astronauts and cosmonauts talk about missing the sound and smell and I'd imagine the texture as well. Because a lot of them do when they land they smell the grass, touch the earth, touch the grass, be emersed back in, you know, where we are born.

[sounds of the forest and rain]

Cassidy 34:13

I hope you found this episode as eye opening as I did. Before researching for this I had virtually no knowledge of Mars space travel or the type of extraterrestrial life scientists were searching for. Even though I always felt like space travel was cool, and there must be some type of life form somewhere in the universe. I never really considered what it all meant. In the very near future, our whole perception of life could change. The ExoMars Rosalind Franklin rover, the first of its kind could drill into Mars's surface and find evidence of past life in the next few years. And if that life is found to have formed independently, then that can mean there are an infinite number of life forms throughout the universe. On the other hand if evidence of life is not found, the fact that they had the same conditions as us at one time, but didn't form life like we did, that begs the question of what is so special about Earth that allowed for life to form? And as long as no current life forms are found on Mars, we could have the first people going to Mars in our lifetime. How amazing is that?

[theme music]

Cassidy 35:32

Thank you for listening to Made at UCL, the podcast.

Cassidy 35:35

To listen to previous episodes or find out more about life at UCL visit www.ucl.ac.uk/made-at-UCL, or subscribe wherever you listen to this podcast.

Cassidy 35:52

This episode was presented by me, Cassidy Martin and produced by Cerys Bradley. It featured music from the BlueDotSessions and additional sounds from freesound.org.

Cassidy 36:02

Special thanks to Andrew, Ian and Iya for sharing their time and expertise.

Cassidy 36:08

This podcast is brought to you by UCL Minds, bringing together UCL knowledge, insights and expertise through events, content and activities that are open to everyone. I hope you enjoyed listening as much as I enjoyed interviewing our guests this month. Thanks again for stopping by. Take care of yourself and each other

Close

Close