S2 Ep3: Pain: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

MORE ON THE STORIES

CREDITS

Pain Insensitivity

- Tbrook Switch Light 04

- StarRock gas stove

- Coral_Island_Studios Women in Pain

- Plasterbrain Computer Sounds

- Eschwabe3 Ship Radar

Dentistry

- Cheeseheadburger Dentist Drill

- 15GPanskaSupsakPtrik 05_Gargling

- 14FSmitakovaK 7-14-Crying

- Wubitog Slime attack or movement

- InspectorJ www.jshaw.co.uk Buzzing, Electric Lamp, A

- Chrisbrowne626 Tooth Tapping Sound Bit

Photography

- Caitlin_100 Knife scrape

- Filipe Chagas Lemon,Juicy,Squeeze,Fruit

- InspectorJ www.jshaw.co.uk Dripping, Fast, A

- Bsumusictech walkingintheleaves

- IENBA Apple fall and rolling

- 775noise Biting into apple

- Zerolagtime 20070317_garbage_truck

- uEffects Camera Focusing and Shutter

- adafdf Pills hit floor_adams

- Daikirai pill_bottle_roll

- Inspector J www.jshaw.co.uk Printer, Distant, A

TRANSCRIPT

Episode Three: Pain: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Introduction

F/X: Theme music

Hello, I’m Cassidy and welcome to the third episode of series two of Made At UCL, the podcast.

This podcast tells the hidden stories behind UCL’s innovative research and gets to the heart of UCL’s community work. In this month’s episode, we are exploring Pain the Good, the Bad and the Ugly sides of this sensation. First, you’ll hear me interview a researcher who works with people who feel no pain and you’ll get to find out why pain is necessary for our health and survival. After that, we have an innovator who has designed a new material for dental fillings that will make the procedure much less painful and that trip to the dentist - not nearly as terrifying. And finally, we have an artist whose unique blend of medical research and fine art photography is helping chronic pain patients visualize and more accurately communicate to their doctor the notoriously difficult to describe experience of pain. Through these research stories we’ll show how the feeling can be ugly, vibrant, informative and experienced differently by all.

Montage

James: So pain is that unpleasant sensation that you experience when, for example, you burn yourself or cut yourself

Anne: Hot and cold on the teeth.

Deborah: I think I would describe pain as being indescribable.

Anne: Agony

Deborah: massive

Pain gene

Cassidy: To begin our journey into pain I wanted to figure out how and why we experience pain in the first place. I sat down with Dr James Cox , a senior lecturer at the UCL Wolfson Institute for Biomedical Research. His research aims to understand the mechanisms in our body that determine when we feel pain. And he does this by working with people that don’t feel any pain at all.

James (00:24): … In my lab, we work with patients who are born, and who are pain free, and have these rare inherited pain disorders. And we try to find the genes that are mutated to cause that particular phenotype.

Cassidy (03:06): what is a phenotype?

James (03:11): So a phenotype is an observable characteristic. So if you have a change in a gene… then you can see that in a phenotype, for example, a change in eye colour, or a change in height.

Cassidy (00:46): And can you give us a definition of what pain genetics is.

James (00:53): So pain genetics is the study of the genome to identify genes that are changed and are the cause of a particular pain phenotype. And that can be patients who are pain insensitive, or patients who may have chronic pain disorders, but what we try to do is try to find the changes in these genes that are responsible for these phenotypes. And then potentially, these can be new analgesic drug targets.

Cassidy (04:54): … You've worked with a patient named Jo Cameron, who is insensitive to pain. When did you first meet Jo?

James (05:11): I was first made aware of Jo, on my birthday actually, back in 2013…

(06:00) when we received an email from a consultant anaesthetist in Scotland called

Dr Devjit Srivastava. And he had met Jo, because she had visited his hospital for an operation on her hand. (07:39) she had something called a trapeziectomy. And

that was to remove a bone at the base of her thumb that is normally very painful. Jo had spoken to Dev before the operation and said that she wouldn't need any painkillers.

But Dev. I don't think he believed her until when he met her afterwards, and realized that indeed, she was pain free and didn't need any painkillers subsequent to that

operation. And he then spoke in detail with Jo realized that she'd been pain free all her life and has suffered injuries such as fractures, or burns or cuts, that that didn't

cause any pain.

Cassidy (09:28): and I think I read she's only one of two people with it, which is probably why they didn't pick it up, right?

James (09:35): Yeah, well, she's the only person actually in the world that we know of who have these two particular mutations. Her son does carry one of the mutations and is partially pain insensitive, but to our knowledge, Jo is the only person in the world that carry those two particular mutations.

Cassidy (09:56): Wow… So these mutations, where do they come from what causes someone to have like this kind of pain insensitivity.

James (10:06): So Jo has inherited two different mutations, one from her mother, one from her father. And one mutation is a change… in a gene called FAAH.

Cassidy: FAAH, which is spelled F A A H and stands for Fatty Acid Amide (Am - I’d) Hydrolase (High - dra -laze. It’s a gene that breaks down compounds in our body which calm us down. FAAH helps our body to experience anxiety and stress by stopping us from having too many of the chemicals that make us feel calm.

James (cont): What is quite remarkable is that Jo also carries another mutation. That mutation is a deletion,

Cassidy: This means that the mutation involves the loss of genetic material, instead of the change or creation of it.

James (cont): And that mutation is very close to the end of the FAAH gene. And at the time, we didn't know why that particular mutation was causing this phenotype. But we discovered that that deletion actually removes the first two exons of a completely new gene, which hadn't been described before. And we called that gene FAAH-OUT.

Cassidy: Is that purposeful? The name?

James (29:38): It was. The phenotype was so amazing. You know, we thought it deserved a catchy name for the gene (29:17). I love hearing the guys in the lab say FAAH-OUT all the time.

Cassidy: By studying the FAAH-OUT gene, James and his team found something very interesting.

James (10:06 cont): What we've gone on to show is to show that that FAAH-OUT gene… functions as an RNA.

Cassidy: RNA is kind of like an instruction manual that tells our cells how to function. And so this new gene that James and his team discovered is telling other genes in the body how they should behave but Jo’s mutation means that her FAAH-OUT gene carries a different set of instructions, because it has lost part of its manual – those two exons.

James (cont): And we think the job of this gene is to actually switch on FAAH… So Jo has two particular mutations, one in the FAAH gene, which means that this enzyme doesn't work properly, and the other mutation in the FAAH-OUT gene, meaning that this FAAH-OUT gene doesn't switch on the FAAH gene properly. So essentially, she has a loss of function of FAAH.

Cassidy: When the FAAH gene isn’t switched on properly, it can’t regulate the parts of our nervous system designed to stop us feeling anxious or scared or stressed. Which means that Jo is pretty happy, basically, all the time.

Cassidy (14:42): in your research paper. It showed… her level of anxiety was zero and her level of fear as well… I was almost a little jealous. I was like, I wish that I could have that. But then obviously it comes with some negatives as well. Could you tell us what some of the pros and cons are of Joe's condition?

f/x: burning

James (15:17): … pain is such an important physiological mechanism it protects you from damaging and life threatening events. So to not feel pain isn't a good thing, in fact, because… you can burn yourself, you can cut yourself and not realize it and Jo reports many instances of this, for example, she smells the burning flesh when she burns herself on her oven. And then she realizes that from the smell and sees Oh, yes, she has burned herself. So this pain is protective. But (17:37) in addition to being pain free, she also has a happy non anxious disposition. Anecdotally, her wounds heal faster than expected. And she has reduced stress and anxiety responses…. So it's not all bad.

Cassidy (19:04): it's so amazing to me the thought of having no anxiety and being happy you know, I am I'm a very anxious person I had, anxiety and had to been medicated for it and all that kind of stuff… so it's interesting, this idea. I don't know how do I put that I guess it's just like the idea of not having to worry about anxiety at all is I can see why it's bad because I understand the stress response of it and, and but it's also like Wow, that's so nice… What was it like working with this super happy Jo?

James (19:56): It was amazing. I mean, Jo has been so helpful for Research... She's come to London… and has been so patient… the search for the gene took quite a long time. Because the mutations were quite unusual. So we used the conventional approach at the time of doing something called exome sequencing, where we sequence all the exons of the human genome to try to find that pathogenic mutation. And that search didn't lead us anywhere. And so we had to take a different approach, we had to do something where we looked across the whole genome to look for a deletion. And using that approach, we found this, this deletion that that was novel. And that the search then was still ongoing, because we need to understand why that deletion causes this particular disorder. And so it took us time to understand that we discovered a gene that was within that deletion. And then further, we need to understand why removal of that gene affects the gene next door. So she has been so patient and she's been so helpful, and donating blood samples and her DNA for research. (27:22) Actually, it's been so helpful, that Jo has spoken to the media, about her story. And because that has led to an awareness of pain and sensitivity, and clinicians have got in contact with those talents. And they also have patients where pain insensitive and this… enables us to expand our… cohort of patients, and potentially we can find even more genes that that that result in this this pain free phenotype.

Cassidy (35:40): … what are you most hoping to achieve with your research?

James (22:35): … So chronic pain is a myriad of different disorders, you can have chronic pain through osteoarthritis, or from genetic disorders, or form from cancer therapy. So there's many reasons why people suffer from chronic pain. And at the moment, chronic pain is quite poorly treated. I mean, surveys are carried out where about a third of people who are in chronic pain aren't getting relief from their current medications, and they are switched from one painkiller to another to try to tackle that pain. But in a lot of cases, the painkillers just don’t work. And so we need to understand the pain system better. And one way to do that is to identify these key genes that are mutated in pain free people. And then potentially we can target those genes, and they can lead to new and better painkillers.

Dentistry

Cassidy: James’s research has implications for the future of pain medication and, one day, might even help reduce the pain felt by chronic pain patients. However, the pain systems that James is trying to understand is super complex. So, in the meantime, researchers at UCL are having to look at different approaches for reducing pain in their patients. One researcher, who is doing just that, is Professor Anne Young. She’s been developing new techniques in dentistry to help improve the process of getting a filling, making it much less painful and much less intimidating to children.

Anne (00:37): Hello, my name’s Anne Young and I’m a professor at the UCL Eastman Dental Institute.

Cassidy: I spoke to Anne about a new type of dental filling that she has created, why it’s such an important invention, and about the process of development to deployment in the dental industry.

Anne (02:42): So personally, I had to go to the dentist a lot. I've got lots of sterling silver fillings and was really quite afraid of the dentist and a lot of children are and I feel that having made something that can stop them suffering the fear I had is great.

Cassidy (04:51): Oh, yeah. I am terrified. I'm terrified at the idea of it as well,

Anne (04:22): it was terror of not being in control, of not really knowing what was going to happen, of the pain of going again and thinking oh, no, I'm not gonna say yet again you need yet another filling or you're gonna need another tooth taken out… It became a terror going anywhere near a dentist.

Cassidy (05:26): … there's this growing problem… of children needing dental fillings. Why is that becoming such a common problem?

Anne (06:09): Well, I mean, what we've had for about 200 years is the silver mercury amalgam fillings. And so the issue has been that… the mercury in them, if it gets into the water supply, it's very toxic, it gets turned into an organic mercury compounds. And if we didn't eat fish that can cause serious illness. So all mercury across the whole globe has been banned. And as a result of that, there's nothing to make the silver fillings anymore. So those got banned in children in 2018, across the whole of Europe, and they will be banned, possibly, I think, by 2030 in all adults as well. But… really, there's only the white composite is the other filling material we have. So we use that for adults, but it's very difficult to place. And so we've got a lot of young children between the ages three to five that are very, very difficult to treat, you can't get them to open the mouth, they can't sit in the chair, we don't want them to have the kind of phobia that people have had in the past of going anywhere near a dentist. So trying to treat them is very difficult.

f/x: drilling, rinsing, fidgeting, pain

So the composites that we have for ourselves, for adults, they take about half an hour to place, you have to use an injection, you have to use a drill which cause pain, you have to rinse the teeth and that again can cause pain. So it's an if the child won't stay still, the filling won't be placed properly. So it falls out. They don't last very long. So a lot of problems of trying to treat young children, especially the sort of three to five year old age bracket.

Cassidy (10:11): And I imagine that kind of like dental work, the replacement now that they have for the mercury and all the drilling is very expensive as well

Anne (10:22): it's the time of the clinician that really is the biggest cost. I think it costs about 65 pounds… to have a filling placed. And most of that cost is the clinicians time the material itself is maybe about three pounds for the composite material and the other components.

Cassidy (10:49): And how does that compare to the one to what you're doing?

Anne (10:53): We don't need all the other components, you don't need to drill, we don't need to use the anesthetic, we placed the material directly onto the tooth that's decayed… So you can place this in one single step, you can place it in about two minutes, instead of half an hour. So you've dramatically reducing the cost because you're reducing the cost that the of the clinicians time and it's much better for the child doesn't have to be sitting in a chair for half an hour. Trying to keep their mouth open. No injections, a lot less pain, no drilling out of the soft, hot, soft tissue, the damaged tissue.

Cassidy (11:54): … as someone who has a fear of needles, that's very appealing. (12:31) Can you… tell us what this filling is and how it works.

f/x: sound of the putty sliding into the gaps in the tooth and hardening

Anne (13:01): If you have a normal composite for an adult, you just fill the hole that you've drilled. So you've taken out all the decayed tissue, and you just fill it up with this composite, the difference that we've done is we've made small modifications, that actually mean that the composite will penetrate into the tissue that's actually diseased, so you don't have to remove it. So you can leave it in place, you don't have to drill it out, the material penetrates in fully stabilizes, it makes it strong again, makes it so that the decay process stops, it totally surrounds the tooth structure, seals it and converts the tooth back to its original shape, its original function looks exactly like the original tooth. But it also means we don't have to take out as much of the original tooth. And that decayed tooth can actually start to repair itself. So if you can see it effectively, it will start to put down new minerals and harden itself over time. So we're allowing the tooth to repair itself. But also we've got other components in there small amounts of other components, that if the restoration gets damaged, it will actually self seal and it will self repair. So hopefully it should also last longer than another composite material, conventional one, which can get damaged, you can get cracks between the tooth and the restoration. And then you can get bacteria penetrating down and starting off the decay process again underneath. So it's much better for children because it's so much quicker to place. no drilling. No aesthetic.

Cassidy (16:24): … it starts off when so when you put it in, it's like this… liquidy kind of form… it almost reminded me of elmers glue in a way. And then it hardens, within two minutes.

Anne (16:42): it's a paste and you put blue light on it. And with 20 seconds of exposure to the blue light, it will go from being a paste that will flow into all the crevices of the tooth structure into something that is has the properties of the original tooth. So it will feel within a minute exactly what the tooth feels like originally. And that's amazing.

Cassidy (17:13): It's amazing to think that you can create a substance that becomes basically a tooth and looks like it feels like it has the same components in a way. (17:43) So, let's talk about getting it out to the public. So pretty soon, hopefully patients will no longer have to go through this currently awful, dental filling process. Recently, I believe you had a successful first trial with six to 16 year olds…

Anne (18:18) So we started we had six children, they were all between the ages of five and 10. And they had teeth that was so badly decayed, that they were having to have the tooth extracted. they had a period of a month where they had to wait to actually between their first appointment and to actually get to have the general anaesthetic. So they were given this material... They were teeth that was so badly decayed, they really would not restorable. But, the material worked, it stayed in place and so much so that several of the children didn't then want to have their teeth taken out. But what we also managed to do is because they then had to have to take taken out, we were able to prove within the lab that this had penetrated right in and stabilized decay... usually you would expect the child to be in pain when they've got these very large cavities. immediately they were out of pain and they were able to cope until they had the appointments to be able to have their tooth removed.

Cassidy (20:34): … I know you're working right now to get this product out there to the public. But… this was a long process made longer by the pandemic, how long do you think it will take before dentists can start offering this alternative?

Anne (21:15): we are just about to try a second trial, we've just got a small amount of funding to do that… hopefully, we should be able to start within about three months… we're planning in the first instance, about 60 children. And that will help us then to get you have to get the CE mark, in order to be able to go to market with the material. So it will probably take us another year after that, after that trial, to get CE marking and to get it out into the general dental practices. (22:21) But so probably within 18 months, two years, it'll be in the hands of the general dental practitioners. Hopefully.

Cassidy (22:57): that's really exciting… I don't know, for some reason, I was thinking it would take way longer than that. So that's exciting to think that possibly in 18 months, we could be able to use this

Photographs

Cassidy: Despite the incredible work of James and Anne, pain will likely always play a part in our lives. It is such a subjective experience, making it difficult to describe to others. And being able to describe your pain can often be the key to a diagnosis, making the experience all the more frustrating.

For this final part of the podcast, I spoke to Dr Deborah Padfield, a senior lecturer at St. George’s University of London and a lecturer at UCL Slade School of Fine Art. Deborah combines medical research and fine art, using photography to help patients explore and communicate their pain. She recently co-edited a book with Dr. Joanna Zakrzewska (Zahk -Shhes-ka)(a pain consultant at UCLH) . You can download the book for free and see images from it on the podcast website. In fact, you may wish to have a look at the ones on our website while listening to the last bit of this story.

Deborah talked to me about the collaborative projects which led to this book

Deborah (01:42) … what we were trying to do is really explore the use of images and the value of images and image making processes in the communication of pain, and trying to see whether having a photographic image between a patient and clinician, how can that actually expand the dialogue and the conversation that happens around it?... And to hopefully make it a handbook or manual that could be used by artists, students, healthcare professionals, and people living with pain and people who care for those in pain. So in a way, it can sort of help them make sense of that experience of pain.

Cassidy: and how she retrained in fine art and photography after her own experiences with pain

Deborah (27:41) I suppose I lived with chronic pain myself as a result of surgery that had gone wrong and possibly exacerbated by an autoimmune condition. And I hadn't really realized its implications,

Cassidy: started to affect her work in the theatre

Deborah: …my life changed when I had about three years where I felt on a unable to do very much really, unless I just had to let go of the very physical work and… the demanding… work in the theater

Cassidy: She developed her collaborative work on a photography exchange programme in the Czech Republic, where she experienced first-hand the importance of communicating pain and of participant-led work.

Deborah: … there was a pivotal moment when I was in the geriatric ward and as a very elderly priest, and I was being taken around with a translator. And there's a very little red tape as who you could photograph or not, you had to be really careful to be as ethical as you could, because actually, you probably could have done anything. But I went in with a camera, and I wanted to photograph him in that setting. And as soon as I went in, he started crying. And I put the camera down, and just held his hand. And I remember, as we were looking at each other, I thought I can't photograph… I can't do this. And at the same time, and he couldn't speak, because the translator said, He's had a stroke, and he wants to speak to you, but he can't. And there was a sort of impasses moment that we couldn't cross, and the photograph I would like to have taken, but I didn't take. But almost that photograph I didn't take has probably been the seed of all the subsequent work I've done… Because I think in a way, what I was wanting to photograph was this, this pain of in communicability, and the pain of isolation and the isolation of pain.

Cassidy: Deborah, working with Joanna as well as, Dr Amanda Williams, and staff and patients from UCLH, and building on previous work with Dr Charles Pitherat St Thomas’ Hospital, uses her research to help people explore their pain through photography and what I really wanted to share with you is our discussion of some of the photographs that this work has produced.

f/x: knife in fruit, dripping, knives being unsheathed

Deborah (41:00): this is one of the images which is very graphic... And I normally if I showed this… with fine arts students and with medical and healthcare students… I… now give a trigger warning before I actually share this image, because there was one time when a medical student nearly fainted when he saw this image… But I think what I like about this image is very visceral, it is literally a strawberry, it's a piece of fruit, but it's very organic, it's very vivid and very red. And the person who I made it with, had brought the strawberry in, in fact, she brought a whole selection of different fruit and the strawberry seemed to be the most, the most epicyte one. And then she pierced this knife through its flesh, it went in through one side, and it came out through the other. And you can see the juice at the straw, which is weeping down the side. And it could be blood, it could be bleeding, it could be emotion. And I think there are interesting things in that the very often when we reach for a metaphor to describe pain, we often reach for tools that might be inflict damage, or harm to us. So knives and pins and razor blades. And things which cut or actually create damage are almost the metaphors we reach to you for frozen of an invisible damage as it were. But I think at the same time, this particular person was also waiting for surgery. And so in a way, and her surgery was really successful, after which she was pain free. So you could see, you could see the knife as being a metaphor for pain, and quite a classic metaphor for pain. But you could also see it as anticipating looking forward to the surgeon's knife, which could actually be healing, and ultimately was healing. And so I think there's a very nice thing about the ambiguity of photographs that I think you get this image is quite a good example of as the colors are simple, it's just red and black. And then the knife.

Cassidy (43:29): … I think… when people see it and why maybe they're so disturbed about it is because the strawberry, it's got that soft kind of ness to it, that like is similar almost to like the fleshiness of our our skin. And then of course, as you talked about the stuff that that's going down the side there, it looks like… maybe a mixture of… tissue… coming down… but I love that you talked about that it has both positive and negative association… with the surgery that turned out to be like a really good thing, but also because of the pain that she was having…

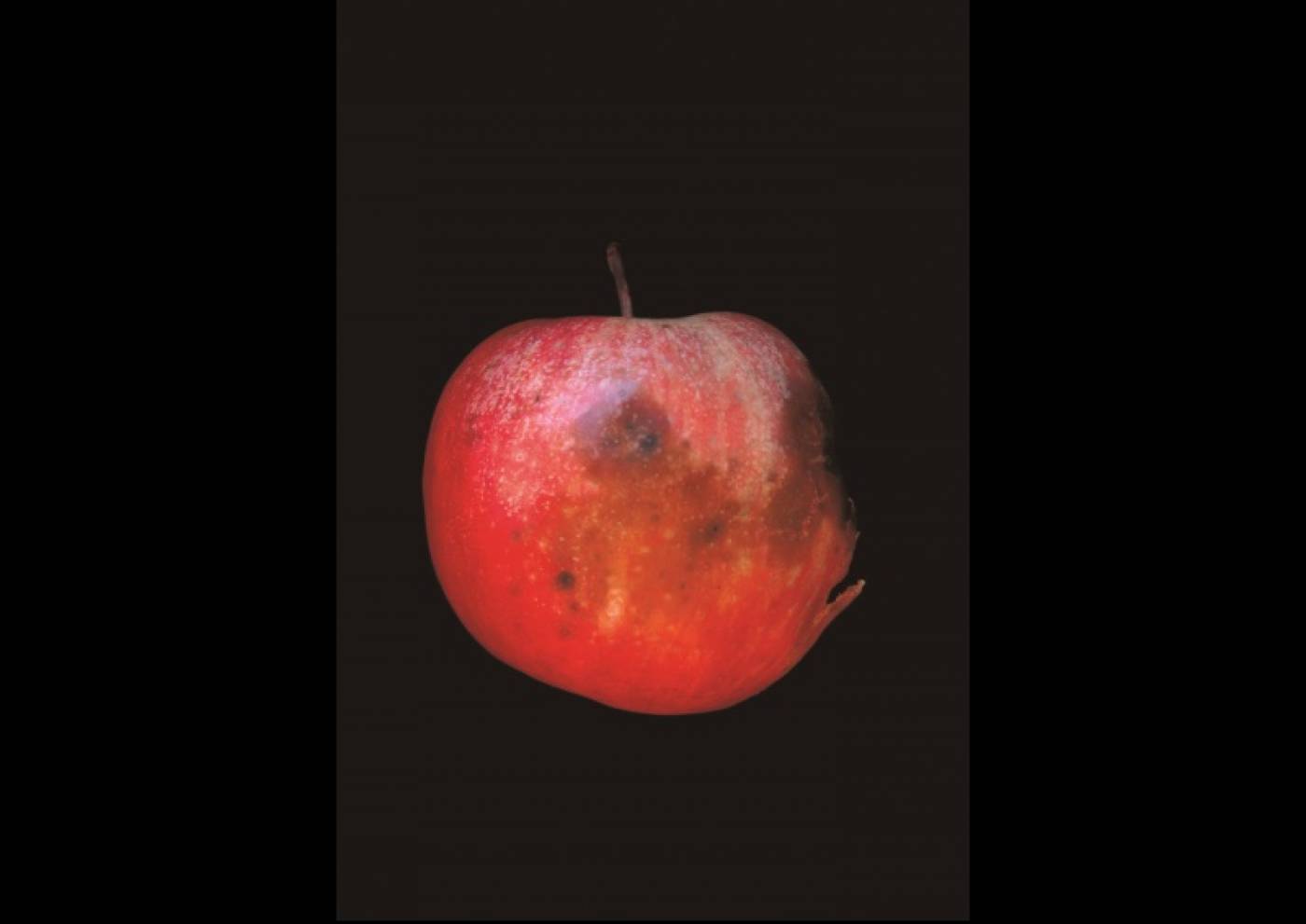

f/x: apple growing and decaying, apples falling, apple being eaten

Deborah (44:22): Well, I think the thing you said it's almost like this internal elements or the guts or something of the flesh in us that almost should be contained inside and is spilling outside. And I think that actually relates to the next image is going to talk about which is a rotten apple. And that was co created with someone in the first project at St. Thomas's. And it was where he just said that his pain that... living with pain is like being a rotten apple because it's really rotten in the inside. But no one can see it. And it's only by the time it's really bad. It's actually worked its way to the skin and the surface of the apple that people can actually see it… and so… with that particular process of collaboration, he… actually provided the apples and the whole range of, of apples in different stages of decay. And then we photograph them. And he chose which image he thought would work for him, because this one coincidentally almost looks like a profile. But I think it also has that sort of that degree of sort of seeing the self as being involved in this quite negative process of decomposition, which could be literally physically, and can also be sort of psychologically and emotionally, that there's a sort of negative process that's going on, which is not a sort of health giving process that you might associate with an apple fruit. But it's a negative process, which is eating away at you both physiologically and emotionally. And I think that theme is repeated in many of the images that I've co created with people, both within projects in the UK, and also with subsequent projects in India and in and in Japan… But there's the sense of sort of buildings crumbling or something, something be not as fruitful and life giving as it should be.

Cassidy (46:37): I was just looking at the image. And I was thinking about how it relates to you because it's, it's bruised. It the rotting kind of almost looks like, like bruising or if I think of… when you get the blood… under the skin, and then it's like this dark kind of purple… color. It kind of reminds me of that.

Deborah (47:04): That's wonderful. But that's the thing is it's almost… a sort of bodily recognition as your body physically remembering this sense of bruising. And I sort of hope that you bring an image into consultation and that physical sort of embodiment of that pain is there in the image there is a materiality, there's a physicality to it, which both patient and clinician can share.

Cassidy (47:31): That's awesome. Let's… go on to the next one.

f/x: rubbish dump, photography, pill bottles rattling and falling

Deborah (47:38): This… image is actually from the first project again at St. Thomas's. It was where someone described themselves as a rubbish dump. And they wanted me to go and photograph their rubbish dump. So I found one hanger lane and photographed it… and when she saw the rubbish dump, she had also brought medication packets. So she then threw her medication across the, the print of the rubbish dump. And we rephotographed it from above. And because of the difference in scale, because it was like a rubbish dump. It's become quite small within the image, but the enormous medication packets and pills thrown across it, it means you focused on the medication because the scale is completely wrong, as well as the sort of maybe the patterns or scarring on the wall behind and this sort of sense of detritus and things that are abandoned on the ground. And she said when she took this image, into… her consultation of the consultant said to her, Well, you know, you've actually got stomach pain, but you're talking about how you feel about the medications. Yes, that's what I need to talk about. Because what happens is, every time they get my medication, right, someone comes along and changes it and everything gets unsettled, and then she feels like everything else in her life unravels. And that sense of medication being actually quite a contested issue. So people both want to reduce it both don't want it and also absolutely want more of it. And the more they have over a length of time, the less effective it becomes. And I'm talking specifically about people with chronic pain… it becomes a very contested area of discussion. And this image and other images which you've got medication are selected time and time again by other people actually using them in the clinic.

Cassidy (50:42): It's interesting, like this image is in black and white, and then you have this, this medicine that seems to be just kind of… floating in the air. And I feel like when you're in pain, or you're going through something it feels like almost like an out of body experience. Or even like with pain medication, you're feeling like out of bed, and you're kind of twirling around.

Cassidy: Deborah’s work enables people to communicate pain, something that is indescribable and complex and deeply personal. She hopes that this work can help patients express their pain and empower them in conversations that we need to have but often avoid.

Deborah (35:57): … Can it be a sort of mediating space, so we both hear each other and thereby leave the conversation with more than we had at the beginning. And I think images and films and visual processes can do that... Because I think it opens up other… types of knowledge... And… I would like it… to be able to affect some change within our understanding of people who live with pain, that they're not making it up, they're not trying to complain, most of them are actually trying not to talk about their pain, because they are worried about the impact on the other person. They want to reduce the anxiety of the other person, they also don't want to feel stigmatized. If I could change something of that through the images, it would be fantastic. If we could raise awareness of certain pain conditions and also raise awareness of the challenges of living with pain… And yeah, if I could contribute to experiences for pain patients as they go through the hospital system, if we can maybe rethink how we can have difficult conversations where we have different perspectives and think could images be useful within that?... So if an image can open up, how we respond to each other, how we encounter each other, you know, I'd be super happy.

Cassidy: Encountering Pain: Hearing, Seeing, Speaking is available to purchase via the UCL Press website. It is also available to download as a free PDF alongside hundreds of other works by the UCL community. You can also find tickets and information about a free launch event for the book in the podcast description.

Cassidy:

This month we explored how to communicate, alleviate, and mitigate pain. Deborah’s research uses photography to help patients more accurately describe their experience of pain when words and things like pain rating scales fall short. James’ work with a patient who does not experience pain helped him and his team discover a gene mutation that could prove vital for developing pain relievers for chronic sufferers. And Anne’s work will make the normally dreaded pain we almost all have to face at the dentist a thing of the past.

Outro

Thank you for listening to Made at UCL, the podcast. To listen to previous episodes or find out more about life at UCL, visit www.ucl.ac.uk/made-at-ucl or subscribe wherever you listened to this podcast. This episode was presented by me, Cassidy Martin and produced by Cerys Bradley.

It featured music from the Blue Dot Sessions and additional sounds from freesound.org. A special thanks to James, Anne, and Deborah for sharing their time and expertise.

This podcast is brought to you by UCL Minds – bringing together UCL knowledge, insights, and expertise through events, digital content, and activities that are open to everyone.

I hope you enjoyed listening as much as I enjoyed interviewing our guests this month.

Thanks again for stopping by. Take care of yourself and each other.

Close

Close