This is a summary of UK Copyright law highlighting the points you may need to know:

Within this page

- What is copyright?

- Copyright and Intellectual Property

- What is protected?

- How long does copyright last?

- When can copyright material be copied?

- What does Fair dealing mean?

- Non commercial research and private study

- Instruction and examinations

- Quotation

- Disability exception

- Text and Data Mining

- Films, broadcasts and audiovusual works

- Licence schemes

- Creative Commons

What is copyright?

Copyright is the legal protection given to a piece of original work as soon as it is fixed in some form, such as written or drawn on paper, in an audio recording, on film, or recorded electronically. It is a form of limited monopoly which benefits the copyright owner. Usually the first owner is the person who created the work. If the work is created in the usual course of the author's employment then copyright may belong to the employer. Copyright is a limited monopoly designed to protect creators of original work.

The creator of the work owns the exclusive right to make copies of their own work and issue them to the public. If you infringe that right by copying or publishing a protected work without permission you could be sued for damages. The law also restricts making copyright works available to the public - such as via the internet. Criminal charges can result from serious or large scale infringement.

There are further acts which are restricted. If you wish to adapt a copyright work, for example by translating it or writing a dramatised version then you also need permission from the copyright owner. The same is true if you wish to stage a performance of a play which is still in copyright.

The showing of films and playing of music (or other protected sound recordings) in a public context also require permission from the copyright owners.

In the UK copyright arises automatically once a work is fixed. There is no registration procedure. To enjoy copyright protection the work must be original, that is to say it must be your work, not copied from someone else.

Copyright is also a commodity which can be sold, licensed or left in your will in the same way as other forms of property. If you transfer it to someone else you are said to "assign" your copyright and that requires a written agreement.

There is no copyright in ideas, only in the way those ideas are expressed. If you were to publish a paper describing the theories of someone else but entirely in your own words then it is unlikely to be copyright infringement although it may be plagiarism.

The legal framework is laid out in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Although updated, the linked version may not always include the most recent amendments to the Act.

Copyright and Intellectual Property

Copyright is one of a family of intellectual property rights (IPR). Other examples are patents, trademarks and design rights. The website of the Intellectual Property Office (UK IPO) includes an explanation of each type of IPR.

What is protected?

The categories of material protected by copyright as they appear in the legislation may seem dated. However works in modern, digital formats have been assimilated into the traditional categories and are certainly protected.

Literary, dramatic, musical works

Literary works are defined as anything which is written, spoken or sung and include among other things published books, poetry, blog posts, diary entries, tables, compilations, computer programs and databases. Dramatic works include plays and works of dance or mime.

Artistic works

This is a wide category, including paintings, photographs, maps, charts, plans, engravings, sculpture, art installations, buildings and models of buildings.

Sound recordings, films, broadcasts or cable programmes

Sound recordings include spoken word material. Films include any kind of video recording. The soundtrack is treated as part of the film.

Typographical arrangements of published editions

This means the way the words are arranged on the pages of a literary, dramatic or musical work. The copyright in a typographical arrangement usually belongs to the publisher of the particular edition and it arises even if the work itself is out of copyright.

Web sites and online content

Content on web sites is also protected by copyright although this may not be clearly stated on the site. In terms of copyright law a piece of writing on a web site is a "literary work", an image (a photograph or a drawing for example) is an "artistic work" and a video on YouTube is a "film".

In order to copy or reuse web content you need either direct permission from the copyright owner or the benefit of a licence or a copyright exception, just as you would for material in any other format. Sometimes web sites carry their own copyright information, often in a footer. Sometimes the site or an item of content will carry a Creative Commons Licence, which defines what you are permitted to do with the content without seeking further permission.

How long does copyright last?

The length of time during which a work is protected depends on its type.

- Literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works are protected for 70 years after the death of the author. By way of example, the published works of an author who died during 1950 will not come out of copyright until January 2021.

- Films are protected for 70 years after the death of the last to die of the director, author of the screenplay/dialogue or composer of the soundtrack.

- Sound recordings are protected for 70 years from the year of publication (release). If they have not been released or publicly performed they are protected for 50 years from the end of the year in which they were made.

- Typographical arrangements are protected for 25 years after the end of the year in which the edition was published.

- Uppublished works created before 1989 commonly have a copyright term which expires at the end of 2039.

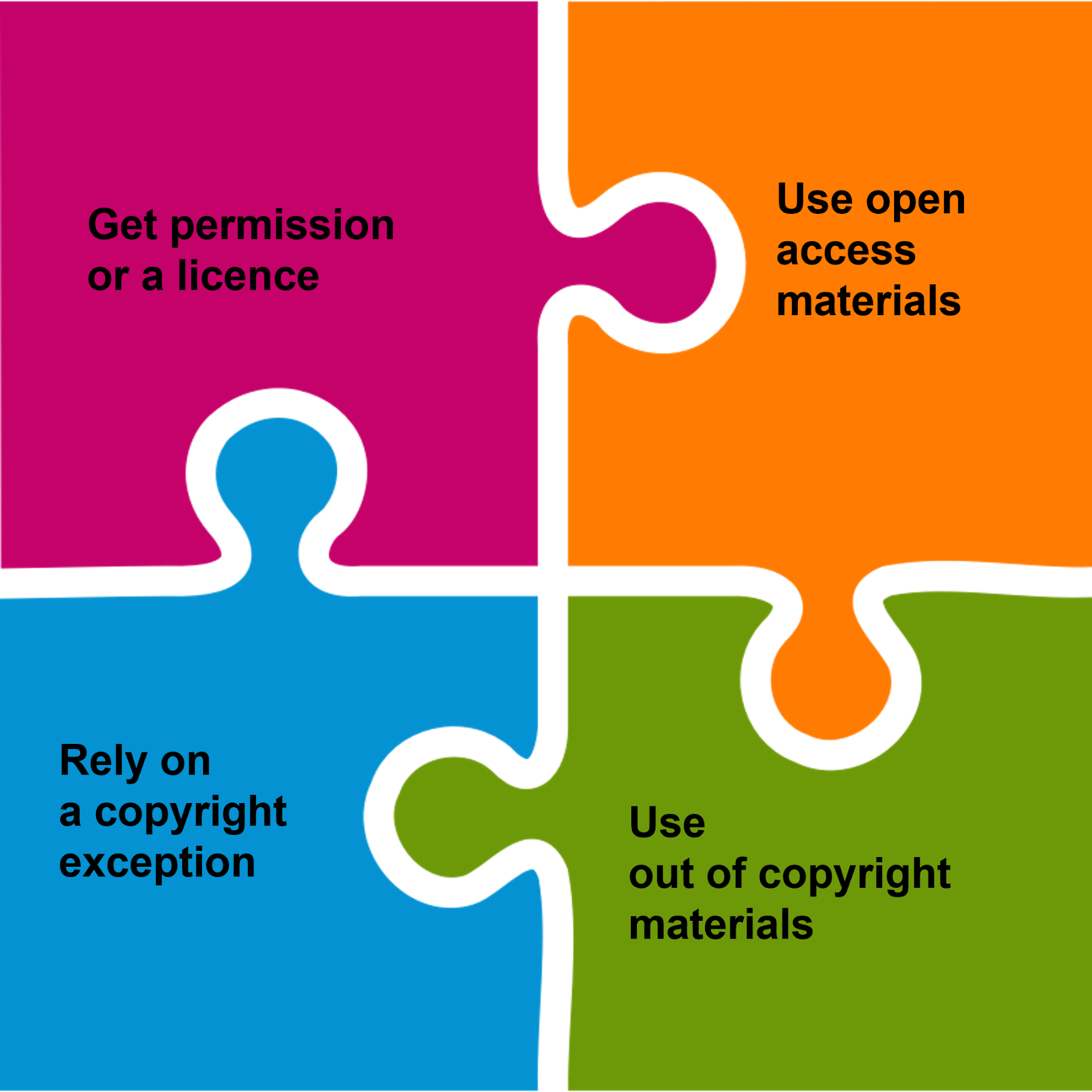

When can copyright material be copied?

Copying material that is protected by copyright usually requires the permission of the copyright owner. Obtaining permission directly from the owner is the most certain way of ensuring that your reuse of a copyright work is legal, but there are other possibilities.

In some very specific circumstances you can copy without permission under the exceptions to copyright contained in the legislation. The most important of these are fair dealing exceptions, although there are other exceptions under the legislation which are also relevant to UCL.

You need to be sure that the exception really does apply before relying upon it. Questions to ask:

Is this particular exception intended to cover what I want to do with this work?

Does the way I plan to reuse this work pass the "Fair dealing" test? This question must always be examined in the context of the specific exception. More about this in the following paragraph.

What does Fair Dealing mean?

There is no concise legal definition. "Fair Dealing" depends on the context and on the relevant exception to copyright. Guidance from the UK Intellectual Property Office states that the key question is "How would a fair minded and honest person have dealt with the work?" Important questions to consider are:

Could the economic interests (or other interests) of the copyright owner be damaged by our use of the work? Is it a substitute for purchase, for example, or will we be competing with the original work?

Are we using a greater proportion of the work than is reasonable and appropriate in the circumstances?

It is also vital to credit the author and source of any work which you use. Fair dealing should not be confused with the broader US concept of "fair use" which is not relevant in the UK.

These are some of the more important fair dealing exceptions:

Non commercial research and private study

The exception for fair dealing for the purpose of non commercial research and private study allows you, as an individual, to make copies for the purposes of your own private study. Only a single copy of each extract is permitted and it must not be shared with others.

The amount that can be copied under fair dealing is not generally specified but reasonable limits must be applied in the particular circumstances. A good rule of thumb is a maximum of one article from a journal issue or a maximum of 5% from a book.

Anyone using a library photocopier or downloading an extract from the internet for personal use (unless under the terms of a licence) is relying upon this exception and should therefore take care to be compliant.

For example: as a student you may make a photocopy or scan a book chapter that you need to read for an assignment. You may only use this copy yourself and it should not be passed on to others.

Instruction and examinations

The Act permits copying of extracts for the purpose of "illustration for instruction" and for examination by way of setting questions, communicating the questions to candidates or answering the questions. The emphasis on "instruction" makes it clear that this exception can be used to copy material for use specifically in a teaching context, as long as it is fair dealing.

This would not cover the use of the same material for other purposes such as longer term storage in a virtual learning environment for retrieval on demand although temporary storage on a secure VLE as part of the instructional process may be covered.

Copyright material in any medium, including for example film and sound recordings are within the scope of this exception. The instruction must be "non commercial". It follows that using this exception in the context of fee charging CPD courses would not be appropriate.

For example: you may wish to include images from printed sources within your thesis or dissertation for examination purposes. This is permitted under the exception, as long as it is fair dealing. Copyright issues will arise however if your thesis is then made available online or published, since that is a diferent context and the examination exception would no longer apply.

Copying certain material may be acceptable for purposes of submitting your thesis for examination, but reproducing the same material for publication would not be covered by the exception for instruction and examination. Unless it is covered by a different exception, you will need to ask the copyright owner's permission.

Please refer to our e-Theses pages for further information on this.

Quotation

This fair dealing exception permits quotation of limited extracts from copyright works of all kinds in any context as long as the use of the quoted material can be defended as fair dealing. It is always advisable to keep the extracts which you quote as short as possible.

Although this exception is very wide ranging, you must be sure that your use of the quotation will pass the fair dealing test. Otherwise you may be infringing the copyright in the original work. The author and source should always be properly acknowledged.

This exception should be used with great caution in any context which could be thought of as "commercial". It is safer to seek permission from the copyright owner in those circumstances.

Disability Exception

This exception allows copyright works to be copied into an accessible format for individuals with disabilities or for the benefit of persons with disabilities generally. This applies to any disability which limits access to copyright works and is to be found in Sections 31A and 31B of the Act.

This covers all types of copyright work. For example it would cover copying a text into a large print version, adding subtitles to a film or copying text into a format which is more accessible for persons with dyslexia.

The main limitation is that if a version in the required format is already available on reasonable terms then we should buy that rather than make a copy. This is not a fair dealing exception and is not subject to that test. The whole of the work may be copied for example, as long as the other conditions are satisfied.

Further information on accessibility at UCL

Text and Data Mining

The new (2014) exception for text and data mining (TDM) is potentially very significant for research projects. The techniques of TDM enable the analysis of large collections of data or published material in new ways using advanced computing techniques to bring to light previously unknown facts and relationships between factors.

TDM involves copying the data in order to analyse it and in cases where the material is protected by copyright, such as the content of e-journals, this would usually require permission.

The exception permits TDM to be carried out on copyright works as long as it is for a non commercial purpose. This means that permission from the copyright owner is not required. The exception cannot be over-ridden by the terms of contracts with publishers. TDM is not tied to the fair dealing test.

Films, broadcasts and audiovusual works

These are all protected by copyright and there are often multiple rights subsisting in the same work, such as in a film and the script and music for the film.

There is an exception which permits the showing or playing of films, live broadcasts and sound recordings for educational purposes to an audience which consists entirely of students and staff at an educational establishment. This clearly covers the clasroom context but not film clubs or similar activities.

The inclusion of brief extracts from films, broadcasts and sound recordings in a teaching context may be covered by the "Instruction and examinations" exception.

Licence schemes

UCL holds a number of "blanket" licences from organisations representing the interests of a wide range of copyright owners.

These licences mainly permit the copying of material to be used in teaching materials and course packs. These blanket licences are therefore very relevant to copying by UCL staff but they are not usually relevant to copying by students. They include:

The CLA Higher Education Licence, which enables copying and scanning from printed sources to support groups of students on a course of study and the storage of digital copies in a secure environment.

The NLA Media Access Licence, which permits copying of extracts from newspapers.

The various UCL medical libraries also provide access to copyright material to UCLH NHS Foundation Trust staff and students under the terms of the CLA NHS England Licence. This is quite separate from the CLA Higher education licence.

The Educational Recording Agency (ERA) Licence which licenses the recording and storing of broadcasts for educational purposes.

The BoB (Box of Broadcasts) service may be used by UCL staff and students. It works in conjunction with the ERA Licence (see above).

Students and staff can search the BoB web site for past TV and radio broadcasts from a wide range of channels. Past and current broadcasts and clips from broadcasts may be stored on the user's personal account and used for educational purposes, in compliance with the BoB terms and conditions. This service is delivered entirely via the BoB web site and the broadcasts cannot be downloaded onto a UCL computer.

The Open Government Licence (OGL) allows the copying and reuse of most Government publications, both printed and online publications and is generous in its terms. The licence permits both commercial and non commercial reuse. It applies automatically and is free of charge. It does require that material should be properly attributed. The OGL applies to most materials which are Crown Copyright. A similar licence applies to material which is Parliamentary Copyright.

When reusing a Government publication however you should check for any unexpected items of third party copyright, such as photographs which may be included within the publication. You may need to seek separate permission or edit them out.

Creative Commons

Creative Commons licences are freely available for authors, photographers etc. to licence their own work online. They enable authors to assert copyright in their work while at the same time encouraging others to reuse their content, subject to certain conditions. You can choose from a range of of CC licences, depending on the types of reuse which you are happy to license. The copyright owner can choose, for example a licence which either allows or rules out commercial reuse of their work.

The Creative Commons Licences are very suitable for material posted on the internet, where the copyright owner has no commercial reasons to prevent their content being reused by others and positively wishes to encourage reuse. They are very easy to apply. If you think that your work has potential commercial value however you should think very carefully before applying a CC licence to it.

Another note of caution: You may be able to take your material down from the internet if you change your mind about making it available, but you cannot remove a Creative Commons Licence from someone who is already reusing your work under a CC licence. CC licences cannot be revoked.

Using Creative Commons Licensed Content

If you want to find items of content you can safely reuse then you can search popular websites for material published under a Creative Commons Licence The licence accompanying the material (usually represented by a simple logo that links to more in-depth information) will clearly define what types of reuse are permitted.

If you have any queries or need further advice please contact: copyright@ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close