World's largest genome-wide association study for keratoconus uncovers risk factors

1 March 2021

A new study reveals regions in the human genome that predispose an individual to developing keratoconus.

An international study led by UCL IoO’s Professor Alison Hardcastle and Moorfields Eye Hospital’s Professor Stephen Tuft, with the collaboration of Dr Pirro Hysi at Kings College London, as well as researchers from the UK, US, Czech Republic, Australia, the Netherlands, Austria and Singapore, uncovers the genetic basis for the disease.

Keratoconus is a disease that causes thinning and distortion of the cornea, the transparent layer at the front of the eye. It has an onset in the teens or twenties and, untreated, it can lead to severe visual loss. It is a common disease with an estimated one person in 375 affected in North Europe.

Most individuals with keratoconus are identified by their optometrist and then referred to the hospital. This means that the majority of individuals with keratoconus already have visual loss by the time they attend the hospital clinic. Identifying individuals who are most at risk of developing keratoconus before there has been significant sight loss is a challenge, as we understand very little about the causes of this disease.

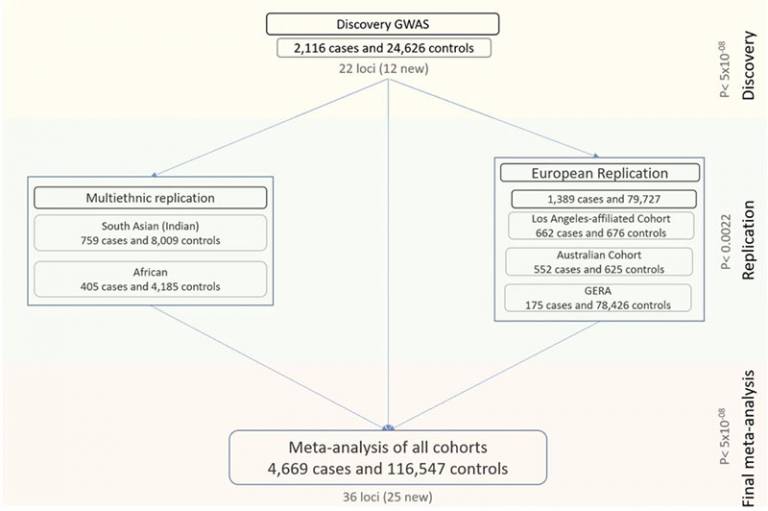

The study, conducted with funding support from Moorfields Eye Charity among others, and published today in Communications Biology, included DNA samples for over 4,600 individuals with keratoconus. The team analysed the human genomes for variants found more frequently in individuals with keratoconus compared to individuals who do not have this condition, known as a genome-wide association study.

The analyses revealed 36 different regions in the human genome that predispose an individual to developing keratoconus. Identification of genetic risk factors at these regions in the human genome has pinpointed some of the mechanisms involved, including problems with the fibres that provide structure for the cornea, and involvement of genes that determine cell identity and maturation.

Professor Hardcastle said:

“We do know that genetic risk factors are likely to play a major role in the development of keratoconus. The challenge was to identify these variants in the human genome. This study represents a substantial advance of our understanding of keratoconus. We can now use this new knowledge as the basis for developing a genetic test to identify individuals at risk of keratoconus, at a stage when vision can be preserved, and in the future development of more effective treatments.

Links

- Research paper in Communications Biology

- Prof Alison Hardcastle's academic profile

- Story on Moorfields Eye Charity's website

- Prof Stephen Tuft's profile on Moorfields Eye Hospital's website

- Story on Moorfields Eye Hospital's website

Image

- Work flowchart showing the flow of the genetic association analyses described in the manuscript.

Close

Close