Opinion: Health Matters - Looking ahead to the health of future generations

11 June 2019

Prof Alissa Goodman, Director of the UCL Centre for Longitudinal Studies & member of Exploring Inequalities project, outlines how life-course research is helping us understand how the health of successive generations is changing & what risks we face for the future

There are many reasons why taking a life course approach to health is important. It’s hard to imagine that we haven’t always known some of the things that we’ve learnt through the power of life course research. For example, just how formative the early years are for laying the foundations for our future health and wellbeing. That there are cycles of disadvantage that cascade across generations. That when health problems occur together, they often have common roots and risk factors. We’ve also learned how cost-effective early intervention and early prevention can be.

Cohort studies and the health of future generations

There is another value to life course research that is growing in importance, as a tool for understanding how the health of successive generations is changing, and what risks we face for the future.

At the Centre for Longitudinal Studies at UCL we run four national longitudinal cohort studies that follow people across life. These are:

- the 1958 National Child Development Study (NCDS)

- the 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70)

- Next Steps (born in 1989/90)

- the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS)

UCL is also the home of the 1946 National Study of Health and Development(NSHD).

Using these, and other life course studies, we can investigate how each generation’s health is changing, compared to in previous generations.

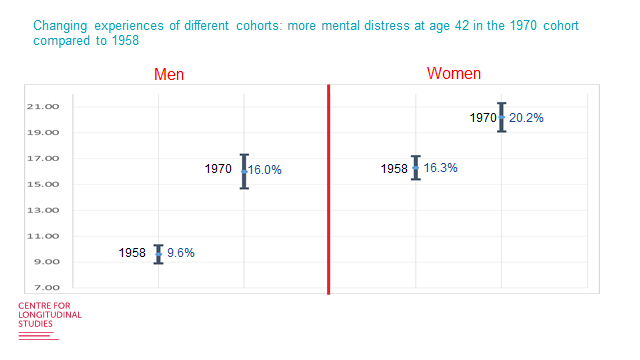

Taking a life course approach allows us to understand how mental health problems in mid-life are changing across generations.

In one study, we compared the mental health of participants in the 1970 British Cohort Study at age 42 to that of participants of the 1958 NCDS when they were the same age, 12 years earlier. The younger cohort experienced significantly greater levels of mental distress, and the differences were most pronounced in men.

These findings chime strongly with the first report from the new Deaton review on inequality, which showed that ‘deaths of despair’ – deaths from suicide and drug and alcohol abuse – are now rising among middle-aged Britons.

Mental health problems also appear to be growing among adolescents. By the age of 14, around 1 in 4 girls in the MCS reported high levels of depressive symptoms (compared to around just 1 in 10 boys) – a statistic which has garnered widespread news headlines. Importantly, in another recent study we compared data from two cohorts of millennials born a decade apart, at age 14. The younger group was made up of members of the MCS while the older group were born in the Bristol area in 1991-92. Levels of depression were substantially higher in the younger generation, and rates of self-harm had risen too.

This rise in mental health problems isn’t just indicative of problems today. We need to plan for the future to take account of the likely knock-on effects on health and wellbeing further down the line.

Overweight and obesity in future generations

The cohort studies can also be used to investigate the change in population overweight and obesity across generations.

Successive generations have become more overweight and at higher risk of obesity, both in childhood and in mid-life. In the MCS, for example, we have found that one in five young people born in the UK at the turn of the century was obese by the age of 14, and a further 15 per cent were found to be overweight.

The child obesity rate has increased almost three-fold in five generations, while adulthood BMI has also risen rapidly across successive generations. Obesity is a leading risk factor for many non-communicable diseases including Type 2 diabetes, for which cases are projected to increase rapidly.

This gives a strong indication to community planners to plan ahead for obesity-related health risks, as well as tackling the problem of rising BMI itself.

Other insights into the life course – population ageing

Findings from these life course studies have informed many other areas of government policy, including how strong the cumulative effects of disadvantage across the life course can be, especially on the risk of poor health at older ages.

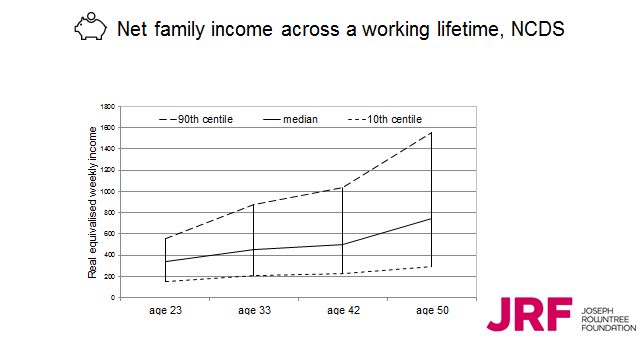

Low income across a lifetime poses strong risks for quality of life in older age, as well as life expectancy. Using the 1958 NCDS, we have shown how income inequality has widened within this generation as they have aged. The figure below shows how the income of the richest 10% grew much faster than the incomes of the middle and of the poorest 10% of the cohort across their working lifetimes.

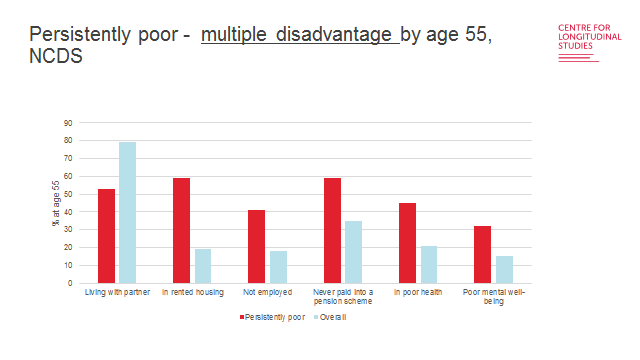

Furthermore, by the age of 55, those who had been persistently poor according to their income were also likely to be insecure in many other ways, including in poorer health, with lower rates of employment, and lack of financial security from either pension or home ownership compared to those who had not been poor. As such, these individuals faced a much stronger likelihood of experiencing difficulties in older age.

Working together to promote health across generations

Many local authorities are already organised around people and place and will be looking at the health and wellbeing of their residents through a life course lens. However, it’s clear that more needs to be done by taking action early, appropriately and together; and by taking the long view.

Chart A: Ploubidis GB, Sullivan A, Brown M, Goodman, A. (2017). Psychological distress in mid-life: evidence from the 1958 and 1970 British birth cohorts. PSYCHOLOGICAL MEDICINE, 47 (2), 291-303. doi:10.1017/S0033291716002464

Chart B: Carpentieri, JD, Goodman A, Parsons S, Patalay P and Swain J. (2017). Lifetime poverty and attitudes to retirement among a cohort born in 1958. Report for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation

Chart C: Capentieri, JD, Goodman A, Parsons S, Patalay P and Swain J. (2017). Lifetime poverty and attitudes to retirement among a cohort born in 1958. Report for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation

> More on Exploring Inequalities

Close

Close