England looking outwards in the 16th and 17th centuries

8 November 2011

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were periods of dynamic interaction between different cultures, as new lands were discovered and the new technology of print enabled knowledge to be conveyed more rapidly and widely than ever before. Print technology also enabled innovative interactions between word and image, in such forms as illustrated books, pictures inspired by texts, and artefacts like maps which combined image and text.

We have tried to represent all these developments in the exhibition ‘Word and Image: Early Modern Treasures from the UCL Collections’, running in the UCL Art Museum (formerly the Strang Print Room) from 15th September to 16th December 2011, and jointly curated by the UCL Centre for Early Modern Exchanges, the UCL Art Collections, and the UCL Library Special Collections. I bring to the exhibition the expertise of a scholar of English literature, so as I survey the exhibits they naturally lead me to contemplate England’s relations with the wider world.

The story they tell me is of England positioned between two competing impulses: to turn inwards and define itself in opposition to the foreign; or to turn outwards and embrace and absorb foreign influences. This short essay will trace these conflicting impulses through three kinds of material: the Protestant iconography of the Whore of Babylon, which travelled across Europe to England; maps (of England by others, by the English of the world); and translations into English of European and classical texts.The pull towards introversion is exemplified by the reception and adaptation in England of the image of the Whore of Babylon. The ‘Word and Image’ exhibition begins with a selection from Albrecht Dürer’s 1498 set of woodcuts illustrating the Apocalypse, the last book of the New Testament (also known as Revelation) in which St John describes a series of surreal prophetic visions. He sees the end of the world, the day of judgement, and the coming of the New Jerusalem. The Whore of Babylon appears in chapter 17 as a gaudily dressed woman riding on a seven-headed beast; the kings of the earth commit fornication with her. She seems to represent irreligion, lust, greed, corruption, and decadence; in short, civilisation turned rotten. (fig. 1).

[image reference is broken]

Fig.1: Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471 – 1528), ‘The Whore of Babylon’, Plate 14 of The Apocalypse (1498), woodcut on paper.

Dürer’s Whore of Babylon became a crucial image in the theological and ideological battles of the Protestant Reformation. Just nineteen years on from his Apocalypse, in 1517, Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the church door in Wittenberg, the event generally seen as the founding act of Protestantism. In 1522 Lucas Cranach, a close friend and supporter of Luther as well as an admirer of Dürer, made a woodcut of the Whore of Babylon which clearly derived from Dürer’s image. The composition was the same, showing the Whore on the right on her seven-headed beast, and the rulers of the world on the left offering her veneration. There were crucial differences, however: in Cranach’s version the crown worn by the Whore has three tiers, alluding to the tiara worn by the Pope; and the cup she carries (described in Revelation as a cup of abominations) has a crucifix in its lid and resembles in shape the kind of chalice used in the Catholic Mass. Protestants regarded the papacy as worldly and corrupt, the Mass as an idolatrous ritual, and objects like gold or silver chalices as profanely materialistic. Thus we see in Cranach’s image a Protestant artist beginning to turn the Whore of Babylon into a personification of the Catholic Church and everything that Protestants perceived to be wrong with it.

The Lutherans produced their own vernacular Bible in German, and through the 1530s and beyond this appeared with an illustration of the Whore of Babylon which made her three-tiered crown resemble even more closely the papal tiara in its bee-hive shape. In coloured versions of the print she was dressed in a low-cut, gold-trimmed scarlet gown, as the kings and emperors knelt before her. The image travelled to England in The Image of Both Churches (1545) by John Bale, a prominent Protestant polemicist of the Henrician court. Of course in the 1530s Henry VIII had broken away from Rome and established the Church of England as a Protestant Church with himself, the monarch, as its Head. Bale’s text included a woodcut of the Whore in the familiar composition, though now she and her beast were on the left while the genuflecting rulers were on the right. The image was accompanied by a quotation from Revelation, and by a caption: ‘The proude paynted churche of the pope / or synneful Synagoge of Sathan’.1 On the opposite page was a woodcut of the Woman Clothed With the Sun, a pure, virtuous female figure from the Book of Revelation, with the label: ‘The poore persecuted churche of Christe / or immaculate spowse of the lambe.’2 This chaste woman, then, personified the Protestant, English Church, set in confrontation with the foreign, corrupt Catholic Church. Bale’s work was immensely popular and influential, going through numerous editions over the course of the sixteenth century.

Meanwhile in Geneva Jean Calvin was leading a Protestant Church that was even more radical than the Lutheran movement. His followers produced a new English translation of the Bible, published in 1560, which was the most widely read English Bible until the Authorised Version of 1611; this Geneva Bible was the text of Scripture used by Shakespeare, for instance. Not only was it translated in such a way that key terms were interpreted from a Calvinist angle; it also included a marginal commentary, presented alongside the main scriptural text in such a way as to carry almost equivalent authority. The verses of Revelation concerning the Whore of Babylon read as follows:

I sawe a woman sit upon a skarlat colored beast, full of names of blasphemie, which had seven heads, & ten hornes.

And the woman was araied in purple & skarlat, & guilded with golde, & precious stones, and pearles, and had a cup of golde in her hand, ful of abominations, and filthines of her fornication.

The commentary read:

The beast signifieth the ancient Rome: the woman that sitteth thereon, the newe Rome which is the Papistrie, whose crueltie and blood sheding is declared by skarlat …This woman is the Antichrist, that is, the Pope with the whole bodie of his filthie creatures … whose beautie onely standeth in out warde pompe & impudencie and craft like a strumpet.3

Thus interpretation of Revelation as a topical allegory of the schism between the two Churches became commonplace, and was presented by Protestants as an authoritative reading of a scriptural truth.

By the Elizabethan period, England felt itself to stand alone as the leading Protestant nation of Europe. The Church of England was not only a Protestant Church but also the official state Church, with the monarch as its Supreme Governor. This encouraged strong identification between Church and nation, and a degree of isolationism as England felt beleaguered by Catholic enemies, especially after the Armada conflict of 1588. All of this had many consequences for literature and culture, as can be seen, for example, in Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene, of which the first books appeared in 1590. The Faerie Queene was an epic romance, but also an allegory of recent history. Two of the principal characters of Book I are Una and Duessa. Una is described as ‘So faire and fresh, as freshest flowre in May’, and wears ‘a garment … / All lilly white, withoutten spot, or pride’. Spenser praises ‘The blazing brightnesse of her beauties beame, / And glorious light of her sunshyny face’.4 She is clearly based on the Woman Clothed with the Sun, and in Spenser’s multi-layered allegorical narrative she represents truth, chastity, the Protestant Church, England, and Elizabeth I. By this stage in her reign Elizabeth I, the Virgin Queen, was widely seen as personifying the virtuous and independent English Church and nation. Una’s adversary, Duessa, on the other hand, is

A goodly Lady clad in scarlot red,

Purfled with gold and pearle of rich assay,

And like a Persian mitre on her hed

She wore, with crownes and owches5 garnished

The which her lavish lovers to her gave. (I.ii.13)

Once again we are in the company of the Whore of Babylon; later, she puts on a ‘triple crowne’ and rides on a ‘Monster’ with ‘seven great heads’ (I.vii.16-17). Duessa represents everything that is the polar opposite to Una: deceit, lust, the Catholic Church, foreignness, and Mary Queen of Scots, widely seen by English Protestants as a personification of all these vices. At one point Duessa is spied unaware as she bathes, revealing that beneath her outward glory she has ‘neather partes misshapen, monstruous, / … more foule and hideous, / The womans shape man would beleeve to be’ (I.ii.41). Later she is captured and stripped, exposing her as ‘A loathly, wrinckled hag’:

Her dried dugs, like bladders lacking wind,

Hong downe, and filthy matter from them weld;

… at her rompe she growing had behind

A foxes taile, with dong all fowly dight. (I.viii.46-8)

Here we see a conflict between two value-systems represented by an opposition between two extreme versions of the female body – one highly sexualised, one entirely desexualised.

Bale’s Image of Both Churches and Spenser’s Faerie Queene are just two examples of an iconography that became commonplace in England in the late sixteenth century. Identification of the Whore of Babylon as the Church of Rome was a polemical interpretation that originated outside England, in Lutheran Germany and Calvin’s Geneva. Yet it was wholeheartedly adopted by English writers and artists to make the Whore a symbol of everything against which the nation defined itself: idolatry, blasphemy, materialism, lust, and corruption. These were positioned as the vices of Catholic Europe, to be feared, rejected, and excluded.

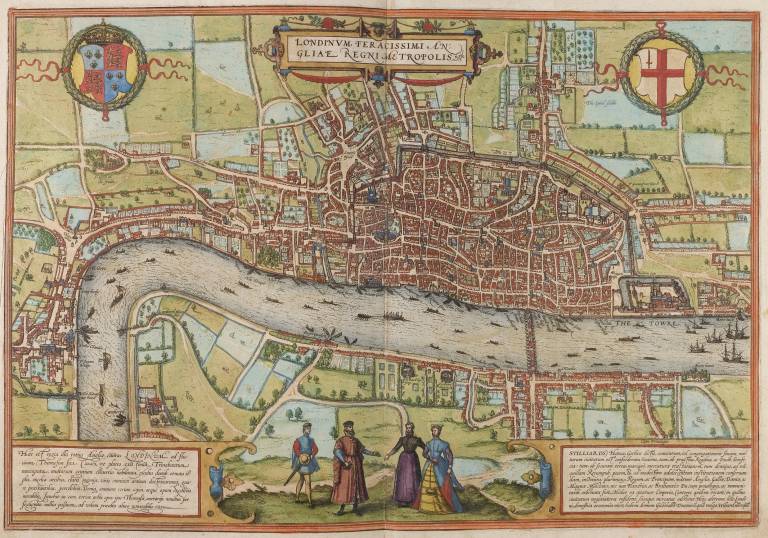

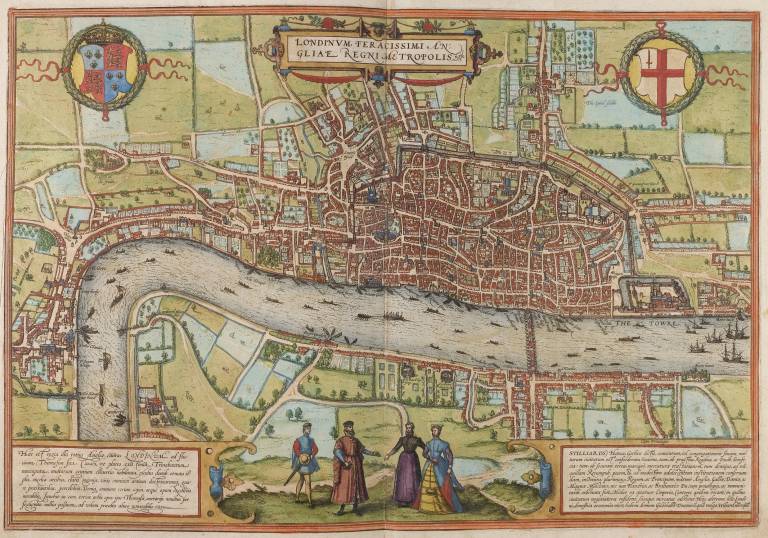

Tracing the iconography of the Whore of Babylon therefore offers a case-study in isolationism, and might leave us with the impression that early modern England was anxiously separating itself from the rest of Europe. However, other materials from the ‘Word and Image’ exhibition offer other stories. The map of London from 1572 by Franz Hogenberg is often reproduced in books about the Elizabethan period because it seems to offer such a detailed and accurate picture of Shakespeare’s city (fig.2). We can see the Tower of London to the east and Westminster to the south west: then, as now, London had two halves, with the commercial centre in the City of London to the east, while the City of Westminster housed Whitehall Palace and the offices of government. The Strand curves between these two districts on the map, following the curve of the river. We can see London Bridge and the playhouses on the south bank of the Thames. We can also see the city walls, conveying a strong sense of boundedness, of definition and limit.

Fig.2: Franz Hogenberg (Netherlandish, active 1594-1614), Plan of London, 1572. Engraving with hand colouring on paper.

Some striking features on this map are the circular structures on the south bank of the Thames. These were the bull- and bear-baiting pits, which would be joined after a few years by the Elizabethan playhouses, also circular in design. Playgoing was regarded by the City of London authorities as an equally idle and disreputable activity as attending bull- or bear-baitings; hence the location of the playhouses beyond the City's jurisdiction, either to the north, outside the city walls in suburbs like Shoreditch (where the Theatre, the first playhouse, was erected in 1576), or to the south, across the river in Southwark. Playhouses like the Globe (built in 1599) were commercial successes, staging plays every day in the performing season; the Globe alone could accommodate around 3,000 spectators. Despite the apparently rigid boundedness of London in Hogenberg's map, only a few years later citizens were regularly pouring out of the city walls, or across the Thames by bridge or boat, to see plays. The walls and the river were porous boundaries, through which much traffic back and forth took place; and by the end of the sixteenth century the spaces outside the walls were where much of the the most creative activity of London was going on.

Another telling characteristic of this map is that it was made by an engraver from the Netherlands, Franz Hogenberg, for a German printer. Despite his map’s detail and apparent accuracy, it is unlikely that Hogenberg ever came to London; most of the maps he engraved were based on the work of other map-makers. This map was just one in a collection of over 500, Civitates Orbis Terrarum, placing London as one among many world cities, and making it available to foreigners, either to visit, or simply to visualise as they read the map. It enables a kind of travel of the mind, and links London and England to Europe-wide processes of cultural exchange.

The desire of the English themselves for contact with other nations and cultures is strongly attested to by another volume containing a notable map, Richard Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations. Hakluyt never travelled further than Paris, where was chaplain to the Englich ambassador for five years in the 1580s. However, he was associated with the publication of over twenty-five travel books, as either editor, translator or publisher. The most important of these was the Principal Navigations, a compilation of first-hand travel narratives by English explorers. UCL is fortunate to possess a rare copy of the first edition of 1589 which still includes a fold-out map of the world, now lost from many other surviving copies of the volume. Hakluyt had patronage at court from several government ministers, including Sir Francis Walsingham and Sir Robert Cecil, who recognised the importance of accurate geographical information for their projects to advance English power in the world.

In fact, despite the tendency to isolationism that we saw earlier, early modern England was hungry for knowledge and ideas from other cultures, as is evident from the vast number of translations published in this period. In the years 1473 to 1640 over 4,000 translations were printed in England, involving almost thirty languages, over 1,000 translators, and roughly 1,200 authors.6 Women writers were particularly active as translators; in a period when publication of original work by a woman was seen as somewhat transgressive, translation was more acceptable as the task of a ‘handmaiden’ serving a male author for a pious or learned purpose. Margaret More Roper, Elizabeth I, and Mary Sidney are just three among a number of notable women translators of the sixteenth century.

Important translations by men include Sir John Harington’s Orlando Furioso. The original Italian work, by Ludovico Ariosto (1474-1533), was an epic romance which was a strong influence on Spenser, Sidney, and others. Harington himself was a favourite godson of Elizabeth I, who wrote humorous and affectionate letters to her ‘Boye Jacke’. Something of a maverick, Harington wrote gossipy letters about court life which are much cited by historians. He also wrote witty epigrams, and seems to have had unusually modern views on religious toleration. He is perhaps most notorious for writing The Metamorphosis of Ajax (1596), a humorous prospectus for a flushing toilet. His translation of Orlando Furioso is surrounded by anecdote and legend: tradition relates that Queen Elizabeth discovered Harington translating some of the racier parts of Ariosto’s text for some ladies of the court. She banished him from court until he translated the whole work, which at some 33,000 lines is one of the longest poems in European literature. The finished volume was lavishly illustrated and beautifully made, standing as a landmark in book production.7

Another notable translation was Florio’s Montaigne. John Florio had an Italian father and English mother, and made a career as a teacher of Italian and author of Italian grammars and dictionaries, catering to a thirst in Elizabethan and Jacobean England for Italian literature and culture. His World of Words, an Italian dictionary, first appeared in 1598, with 44,000 entries; for the 1611 edition it grew to over 70,000 entries. It was remarkable for its comprehensiveness, including terms from slang and regional dialects so that readers could develop a full appreciation of the richness and nuance of Italian literature.

Florio’s translation from French of the Essays of Michel de Montaigne (1533-92), however, was a different kind of enterprise. Again, as with Harington’s Ariosto, the source-text was a highly influential European work. Montaigne had more-or-less invented the essay form, and in these musings on himself had made a major contribution to the development of autobiography. His rational and humane view of life had a huge influence on other philosophers and writers. In translating him, Florio created a notable literary achievement of his own. His distinctive style sometimes embroiders and elaborates, while elsewhere drawing on colloquial English idioms to convey the vigour and immediacy of Montaigne’s prose. To capture Montaigne’s meaning, Florio sometimes invented new words, many of which have passed into common usage, such as ‘conscientious’, ‘endear’, ‘efface’, and ‘facilitate’. His translation was read and drawn upon by numerous English writers, including Shakespeare, who echoed it at length in a passage of The Tempest.8

Florio dedicated the volume to several female aristocratic patrons, and the terms of his dedication are striking: the purpose of the volume is ‘to repeate in true English what you reade in fine French’.9 There is recognition here of the multilingualism of early modern culture, of the linguistic skills of Florio’s readers, and of translation as art. The purpose of this translation is not to make available in English a book that ladies could not otherwise read; as educated ladies, Florio’s dedicatees are perfectly capable of reading French. Rather, reading in their own language will offer a different kind of literary pleasure, and gives Florio opportunities to show off his skill as a translator. The translation is designed not to replace the French text but to sit alongside it, as part of a multilingual culture.

A third significant feat of translation was the version of Ovid’s Metamorphoses by George Sandys. Sandys journeyed in 1610-12 to Venice, Constantinople, Alexandria, Cairo and Jerusalem, travelling partly by sea, partly overland by camel, and published a narrative of his experiences as A Relation of a Journey, 1615. He then turned to Ovid, one of the most important classical sources for early modern English literature; Ovid is the author most frequently alluded to by Shakespeare, for instance.10 The Metamorphoses had already been translated by Arthur Golding in 1565-7, and the level of interest in them reminds us that cultural exchange in this period took place not only between different national cultures and linguistic communities, but also between the early modern present and its classical past. Sandys published a translation of the first five books of the Metamorphoses in 1621; in the same year, he was appointed Treasurer of the English colony in Virginia. He continued with the translation on his outward voyage, later relating that he had done it ‘amongst the roreing of the seas, the rustling of the Shrowdes, and Clamour of Saylers’. He completed it in Virginia. However, his time there did not go well, culminating in a Native American uprising with the deaths of over 300 colonists. Sandys returned to Eng in 1625, narrowly evading Turkish pirates on the way.11 His Ovid was significant for its use of the heroic couplet and its poetic diction, and was an influence on Milton, Dryden, and Pope. The revised edition of 1632 is another sumptuous example of book design. Overall, Sandys presents a fascinating example of travel and translation combined: a classical text, an artefact of the Old World, carried to the New World and there transformed into a modern vernacular version.

This might lead us to dwell on the fact that the word ‘translation’ had several different senses in the early modern period. We tend to think of it as simply meaning conversion from one language to another. However, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it could also mean transition across borders, transfer from one owner to another, and transformation (as in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, when Peter Quince tells the ass-headed Bottom, ‘Bless thee! Thou art translated!’).12 The works discussed in this brief essay present examples of all these senses of translation: Spenser, for instance, takes ownership of the iconography of the Whore of Babylon as the Church of Rome, and transforms it to his own purposes; Harington, Florio and Sandys appropriate and transform their source-texts in order to create their own works of art. The materials discussed here also illustrate some of the contradictions and complexities in early modern England’s relations with the wider world. As we have seen, England partly defined itself in opposition to the foreign, setting rigid boundaries for itself, and seeking separation and isolation. However, at the same time there was in English culture a strong desire to cross boundaries, to explore, to learn, to enjoy dialogue, and to engage in all kinds of exchanges.

1. John Bale, The Image of Both Churches (London, 1545), f.143r.

2. Bale, Image, f.142v.

3. The Geneva Bible: A Facsimile of the 1560 Edition, introd. Lloyd E. Berry (Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1969), Revelation 17.3-4.

4. Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene, ed. Thomas P. Roche, Jr and C. Patrick O’Donnell, Jr (London: Penguin, 1978), I.xii.22-3. All further references are to this edition.

5. Brooches.

6. See Renaissance Cultural Crossroads: An Annotated Catalogue of Translations, 1473-1640, Centre for the Study of the Renaissance, University of Warwick, www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/ren/projects/culturalcrossroads/.

7. Jason Scott-Warren, ‘Harington, Sir John (bap. 1560, d. 1612)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12326, accessed 17 Oct 2011]

8. Desmond O'Connor, ‘Florio, John (1553–1625)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/9758, accessed 17 Oct 2011]; William Shakespeare, The Tempest, ed. Stephen Orgel (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1994), II.i.145-66.

9.Michel de Montaigne, Essayes, trans. John Florio (London, 1603), sig.A2r.

10. See Jonathan Bate, Shakespeare’s Ovid (Oxford: Clarendon, 1993).

11. James Ellison, ‘Sandys, George (1578–1644)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/24651, accessed 17 Oct 2011]

12. William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, ed. Stanley Wells, introd. Helen Hackett (London: Penguin, 2005), III.i.112-13.

Close

Close