UCL Researchers look a little deeper into skin ageing

Our attempts to defy the ageing process are not a modern phenomenon

25 January 2018

Cleopatra wasn't the only one trying to stop the clock

In ancient Egypt early skin lotions included the use of castor oil, as well as Cleopatra's legendary donkey milk baths. The Romans, however, preferred protective balms and skin creams made of beeswax, olive oil and rosewater.

Later, Wu Zetian, the sole female emperor of China who reigned during the Tang-dynasty, mixed her famed 'fairy powder' - made of carefully harvested and prepared Chinese motherwort - with cold water for her morning wash. She was famed for her beauty well into old age.

Beauty may be skin deep but it also has deep pockets

From these humble historic beginnings a huge global industry has grown. According to Statista, the statistics portal, the global skin care market in 2017 will be worth an estimated $127bn. By 2021, that figure is set to rise to $154bn and hit nearly $200bn around 2024.

However, defying the ageing process is more than simple aesthetics. In a recent report by the UK House of Lords, it was suggested that children born after 2010 have life expectancies of 96 and 93 years (for girls and boys, respectively). And while understanding how the human body ages is complex, as more of us live longer it's essential we understand the nature and impact of the ageing process, on our skin and beyond.

So a team at UCL looked a little deeper into skin ageing

The skin is the largest organ of the body, with a total area of about 20 square feet. It plays a crucial role in protecting us from microbes and the elements, while helping to regulate our body temperature. It also enables us to experience sensations like touch, heat and cold.

Essentially, our skin has several layers. These are the stratum corneum and epidermis, the outermost layer, providing a waterproof barrier and creating our skin tone; below this comes the dermis, which contains tough connective tissue, hair follicles and sweat glands; then there's the deeper subcutaneous tissue - the hypodermis - which is made of fat and connective tissue.

Age-related changes have a damaging impact on the structure and functions of the skin. We can all see how these happen at the surface of our own skin as we grow older, but the sources of those changes arise at a molecular level.

And it was these changes that Dr Laurent Bozec, Senior Lecturer in Biophysics and Nanometrology at Eastman Dental Institute, UCL, was asked to study by a global leader in skin care, L'Oréal. Laurent and his team were asked in particular to investigate the use of novel methods that they were pioneering at the time to characterise collagen properties in skin via a feasibility study.

To do so, Laurent led a team of experts right across the University in a year-long consultancy contract. This was successfully arranged and managed by UCL Consultants (UCLC) and led for L'Oréal by Marion Ghibaudo who is group manager of the Dermis Physiology Knowledge and Performance Department, part of the company's Research & Innovation Department.

Laurent commented, 'I have to thank the UCLC team for being at the inception of this positive collaboration with L'Oréal. It would not have been possible without the guidance provided by them. They very effectively set the contract up after protracted discussion, and then stepped out of the way to let us get on with our work in partnership with our client.'

The hunt was on for one of the signs of ageing

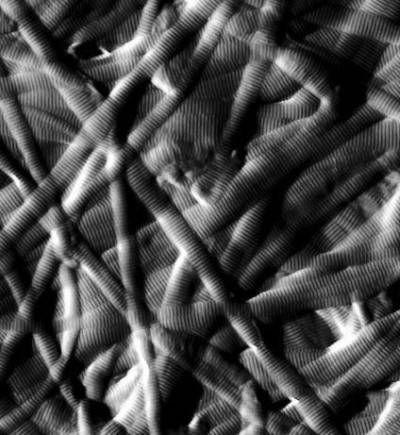

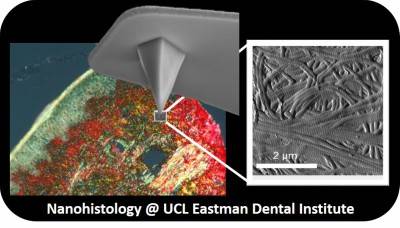

Laurent explained, 'The cosmetics industry often talks about there being so many signs of ageing. Our job was one, to investigate if we could find differences in the properties of the skin as a function of ageing and two, to isolate a single component of the ageing process and better understand it - right down at the nanoscale. So we were working at about one-tenth the size of a human hair. We used a unique and proprietary combination of nanohistology and nanomechanics (Atomic Force Microscopy) to uncover the mechanical properties of single collagen fibrils at a scale of 1/1,000,000 metres. All this work was undertaken on human skin biopsy samples obtained under ethical approval at the UCL Royal Free Hospital.'

Laurent added, 'Collagen is the essential building block in the human body. It's our main structural component and our most abundant protein. How ageing is impacting this structural component was not well understood. That's why we made it our mission to explore this with the latest advanced microscopy set up available at UCL.'

The results obtained by the UCL team highlighted keys differences in both the architecture of the dermis and its mechanical properties as a function of ageing. The novelty in their approach was to investigate the cross-sectional compression of every single collagen fibrils imaged. As a result, we were the first to observe the age-dependent decrease in the transverse stiffness of collagen fibrils. This result seeded a crucial hypothesis in our research group. This was subsequently investigated in detail as part of collaborative Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) award within UCL. This hypothesis suggested that collagen ageing has evolved to maintain a degree of flexibility through the adsorption and binding of water within its structure, despite the apparent loss of hydration from surrounding dermal components. This hypothesis was confirmed experimentally and also through computational modelling.

Laurent concluded, 'Our study, using novel proprietary technology, demonstrated that we could actually see a structural and mechanical difference between young and older skin and the impact of water on collagen in that ageing process.'

This original work, which started as a feasibility study has now opened up a huge research area for Laurent and his team. Further investigative works will undoubtedly follow as the team has already been approached by several industrial sponsors to do so.

Close

Close