Baroque Latinity

an AHRC-funded research network

May 2019 – March 2022

The funded period of this project has come to an end, but the website remains active. The PI and Co-I welcome any contributions, in the form of short essays on 'Baroque Latinity' or items for the bibliography.

Principal Investigator

- Prof. Gesine Manuwald, Dept of Greek & Latin, UCL

Gesine Manuwald is Professor of Latin in the Department of Greek and Latin at University College London (UCL). Her main research interests are Roman drama, oratory and epic as well as Neo-Latin literature. She has co-edited Neo-Latin Poetry in the British Isles (2012), is one of the editors of the Bloomsbury Neo-Latin Series and the main editor of Brill’s Research Perspectives in Latinity and Classical Reception in the Early Modern Period; she is the President of the Society for Neo-Latin Studies (SNLS).

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/classics/people/full-time-staff/gesine-manuwald

Co-Investigator

- Dr Jacqueline Glomski, Centre for Editing Lives & Letters (CELL), UCL

Jacqueline Glomski is Honorary Senior Research Associate in the Centre for Editing Lives & Letters at University College London. Her present work focuses on Baroque Neo-Latin prose writing, especially seventeenth-century treatises on libraries and book collecting. She is the co-editor of, and contributor to Seventeenth-Century Fiction: Text & Transmission (2016) and Acta Conventus Neo-Latini Monasteriensis: Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Congress of Neo-Latin Studies (2015). She has also contributed to A Guide to Neo-Latin Literature (2017) and Der neulateinische Roman als Medium seiner Zeit / The Neo-Latin Novel in its Time (2013). Dr Glomski is a fellow of the Royal Historical Society; she is Vice-President of the Society for Neo-Latin Studies.

https://www.livesandletters.ac.uk/people/jacqueline-glomski

Participants

- Prof. Jan Bloemendal, Huygens Institute for the History of the Netherlands, Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Amsterdam NETHERLANDS / Ruhr University, Bochum GERMANY

Jan Bloemendal studied Classics, Dutch Studies, and Theology. Currently, he is a senior researcher at the Huygens Institute for the History of the Netherlands (Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences), and Privatdozent at Ruhr University-Bochum, and specializes in Neo-Latin drama and Erasmus studies. He is the Secretary to the Amsterdam edition of the Erasmi Opera Omnia (ASD) and general editor of the Brill series 'Drama and Theatre in Early Modern Europe'. He co-edited Brill's Encyclopaedia of the Neo-Latin World (2014).

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Bloemendal- Prof. Paul Gwyne, Interdisciplinary Studies, American University of Rome ITALY

Paul Gwynne is Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Studies at The American University of Rome. His areas of research focus on fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe, the rise and diffusion of Italian Humanism and the reception of the classical tradition. These subjects are reflected in a number of articles and chapters in books as well as a trilogy of monographs which review the production of neo-Latin poetry in Rome from 1480-1600: Poets and Princes: The Panegyric Poetry of Johannes Michael Nagonius (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013); Patterns of Patronage in Renaissance Rome: Francesco Sperulo: Poet, Prelate, Soldier, Spy (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2015); Francesco Benci: Quinque martyres (Leiden: Brill, 2017). With Bernhard Schirg he is the editor of the collection of essays: The Economics of Poetry: Efficient Production of Neo-Latin Poetry 1400-1720 (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2018).

https://aur.edu/node/217- Dr Jason Harris, Centre for Neo-Latin Studies, University College Cork IRELAND

Jason Harris is a Lecturer in History and the Director of the Centre for Neo-Latin Studies in University College Cork, Ireland. He is also the founder and director of the Schola Latina and Conventiculum Corcagiense in Cork, promoting active use of Latin as a research tool. His own research is focused on the intellectual culture of early-modern Europe, drawing upon philological and anthropological approaches to history in order to illuminate Neo-Latin Latin texts. He is particularly interested in Irish Latin writers and in the intellectual circle surrounding Abraham Ortelius. Currently, he is writing a book about the practical impact of Neo-Latin stylistic debates upon the prose style of Irish Latin writers.

http://publish.ucc.ie/researchprofiles/A019/jharris

https://www.ucc.ie/en/cnls/- Prof. Yasmin Haskell, Faculty of Arts, University of Western Australia

Yasmin Haskell FAHA (PhD Sydney, 1996) is Cassamarca Foundation Chair in Latin Humanism at the University of Western Australia, Perth. She has published on Renaissance and later Neo-Latin literature, especially by Jesuits, and its connections with the history of science, medicine and emotions. From 2010-18 she was Foundation Chief Investigator, then Partner Investigator, of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions: 1100-1800, and from 2017-2018, Chair of Latin and Director of the Institute of Greece, Rome and the Classical Tradition at the University of Bristol. She is author of Loyola’s Bees: Ideology and Industry in Jesuit Latin Didactic Poetry (OUP, 2003) and Prescribing Ovid: The Latin Works and Networks of the Enlightened Dr Heerkens (Bloomsbury, 2013), and editor (with Christopher Allen and Frances Muecke) of Charles-Alphonse De Arte Graphica (1664) (Droz, 2005), Diseases of the Imagination and Imaginary Disease in the Early Modern Period (Brepols, 2011), Latinity and Alterity in the Early Modern Period (Brepols, 2011) (with Juanita Ruys), and most recently, with Raphaele Garrod, of Changing Hearts: Performing Jesuit Emotions Between Europe, Asia and the Americas (Brill, 2019). Professor Haskell serves on several editorial and advisory boards, including ‘Bibliotheca Latinitatis Novae’ (Leuven) and the Journal of Jesuit Studies (Brill) and its associated book series ‘Jesuit Studies’ and ‘Jesuit Latin Library’. Her current research interests include Latin in the Enlightenment and Latin written by Jesuits/ ex-Jesuits during the Suppression of the Society of Jesus. She is writing a synoptic monograph about Jesuit Latin poetry and education.

https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/persons/yasmin-haskell- Dr Luke Houghton, Dept of Greek & Latin, UCL

Luke Houghton is an Honorary Research Fellow of the Department of Greek and Latin at University College London. He also teaches Classics and is Keeper of the Scholars at Rugby School. He previously taught at a number of UK universities (including Glasgow, Reading, UCL and Birkbeck), and has held visiting fellowships at the British School at Rome, the Warburg Institute in London, and the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Neo-Latin Studies in Innsbruck. He is the author of Virgil's Fourth Eclogue in the Italian Renaissance (CUP, 2019), and has edited Perceptions of Horace (with Maria Wyke; CUP, 2009), Neo-Latin Poetry in the British Isles (with Gesine Manuwald; Bloomsbury, 2012), and Virgil and Renaissance Culture (with Marco Sgarbi; ACMRS/Brepols, 2018). A new Anthology of British Neo-Latin Literature, edited with Gesine Manuwald and Lucy R. Nicholas, is forthcoming from Bloomsbury Academic. His main interests are Neo-Latin poetry and the reception of Roman authors (especially Virgil, Horace, Ovid and the elegists) in later art and literature.

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/classics/people/honorary-positions/luke-houghton- Prof. Sarah Knight, School of Arts, University of Leicester

Sarah Knight teaches, edits, translates and writes about sixteenth- and seventeenth-century literature, especially English and Latin works. Professor Knight is particularly interested in early modern student life across Europe, and has published widely on the associations between poetic and rhetorical composition, and educational experience. She has a related interest in the impact of multilingualism on early modern writing, especially how authors represent linguistic difference in English, French, Italian and Latin, and other languages. She has edited and translated works ranging from the mid-fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, including Leon Battista Alberti's Momus and the accounts of Elizabeth I's visits to Oxford in 1566 and 1592, and is currently editing John Milton's student speeches (the Prolusiones) and his Epistolae Familiares, and Fulke Greville's two English tragedies Alaham and Mustapha.

https://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/english/people/sarahknight- Dr David McOmish, Institute for Advanced Studies, University of Edinburgh / School of Humanities, University of Glasgow

David McOmish is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh and an Honorary Research Fellow in the School of Humanities at the University of Glasgow. A former engineer and classicist, he has spent the last ten years researching the institutional and literary settings of the new sciences in the early modern period, especially within European and Scottish universities. He has recently published several articles on the Scientific Revolution in Scotland, Italian intellectual culture and its transformative impact on pre-Enlightenment Scotland, and more generally on the role of scientific poetry and Aristotelian literature in the classrooms of Europe and Scotland. His current project at Edinburgh is producing a comprehensive bibliography of all texts used for instruction in mathematics and cosmology at the University of Edinburgh across the 17th century

www.iash.ed.ac.uk/profile/dr-david-mcomish- Dr Victoria Moul, Dept of Greek & Latin, UCL

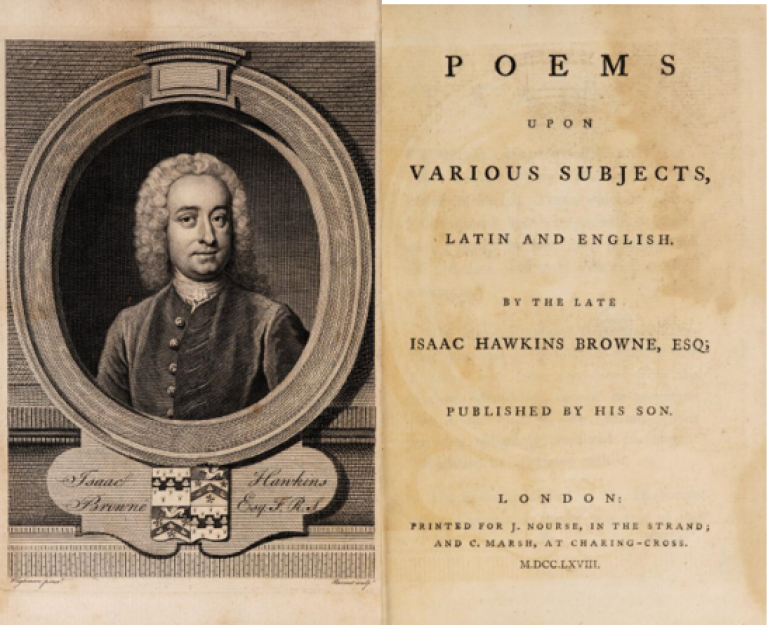

Victoria Moul is a Reader in Early Modern Latin & English at UCL. She works on the Latin-vernacular bilingualism of literary culture in early modern Europe, with a particular focus upon poetry between c. 1550 and 1720. She has published widely on both English and neo-Latin poetry, as well as classical translation and imitation in this period. Recent publications include the Cambridge Guide to Neo-Latin Literature (2017) and a series of articles on Cromwell’s forgotten poet laureate, Payne Fisher. She is currently running a large Leverhulme Trust-funded project surveying for the first time post-medieval Latin verse in English manuscript sources dating from between 1550 and 1720. Her next book, English and Latin Poetry in Early Modern England, will be published by CUP, probably in 2021.

www.ucl.ac.uk/classics/people/full-time-staff/victoria-moul- Dr Lucy Nicholas, Dept of Classics, King's College London / Warburg Institute, University of London

Dr Lucy Rachel Nicholas teaches classical and post-classical Latin and Greek at King’s College London and the Warburg Institute. She is especially interested in projects which bridge the fields of Neo-Latin and Reformation History. Her doctoral thesis comprised a translation and contextual analysis of a Latin treatise on the Eucharist by the sixteenth century English humanist and Cambridge classical scholar, Roger Ascham. Aspects of this have been published as ‘Roger Ascham’s Defence of the Lord’s Supper’, Reformation, vol. 20 (2015) and Roger Ascham’s ‘A Defence of the Lord’s Supper’: Latin Text and English Translation (Brill, 2017). She is currently in the final stages of assembling an edited volume entitled Roger Ascham and his Sixteenth-Century World (Brill, forthcoming) and co-editing two Neo-Latin Anthologies on Britain and Europe (Bloomsbury, forthcoming). She has also written on Thomas More, and her chapter on the Latin Utopias of the early modern period will soon be available in the forthcoming Oxford Handbook of Thomas More’s Utopia (OUP, eds. C. Shrank and P. Withington). Her role as Latin Editor on the Thomas Nashe Project and her participation in the Baroque Latinity Network have brought her into close contact with the writing of Thomas Nashe and Gabriel Harvey. Her current research focuses on the Latin works of Johannes Sturm and Walter Haddon.

https://kcl.academia.edu/LucyNicholas- Prof. Jan Papy, Seminarium Philologiae Humanisticae, KU Leuven BELGIUM

Jan Papy, PhD Classics (1992) and MPhil (1996), is Professor Ordinarius of Latin and Neo-Latin Literature at the University of Leuven. His research focuses on Renaissance Humanism and Neo-Latin literature, with special attention to Renaissance philosophy, the cultural history of the Low Countries, and the history of universities and history of science. In 2003 he was Laureate of the Belgian Royal Academy of Sciences. He has published numerous articles on Justus Lipsius, Erasmus, Vives, and Petrarch. Together with Karl Enenkel he edited Petrarch and his Readers in the Renaissance (Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2006). Last year, he coordinated an exhibition and edited a collection of studies on the Louvain Collegium Trilingue (Louvain: Peeters, 2017). For his exhibition ‘Erasmus' Dream’, he was awarded the Year Price 2018 of Science Communication by the Royal Flemish Academy of Belgium for Science and the Arts. He equally received the Martin Burr Award by the Henry Sweet Society for the History of Linguistic Ideas.

He has been co-editor of Humanistica Lovaniensia: Journal of Neo-Latin Studies (Leuven University Press) (2004–2017) and of Lias: Journal of Early Modern Intellectual Culture and its Sources (Peeters Publishers, Leuven-Paris) (2009–2019). He is currently co-editor of the series Supplementa Humanistica Lovaniensia (Leuven University Press) and member of the editorial board of ‘Erasmus Studies’ (Brill Publishers Leiden).

A full list of his publications is available on:

http://lirias.kuleuven.be/cv?Username=U0016670

Website of the Leuven Seminarium Philologiae Humanisticae:

https://www.arts.kuleuven.be/sph/members/00016670- Prof. Florian Schaffenrath, Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Neo-Latin Studies, Innsbruck AUSTRIA

In the field of Neo-Latin studies, Florian Schaffenrath is especially interested in epic poetry. For his PhD thesis, he published an edition of the poem Columbus of Father Ubertino Carrara SJ (Rome 1715), an epic poem in twelve books about the first voyage of Christopher Columbus to the New World. He has published shorter articles that deal inter alia with Petrarch’s Africa and Sannazaro’s De partu Virginis. As a member of the research group ‘Geschichte der lateinischen Literatur in Tirol’ (published in 2012), Schaffenrath is also interested in the regional history of Neo-Latin literature. He has edited several texts and published numerous articles on the subject of the Tirol. Schaffenrath is a member of the ‘International Association of Neo-Latin Studies’ (IANLS) and of the ‘Die Neulateinische Gesellschaft’ (DNG). At the LBI for Neo-Latin Studies he was a key researcher in the ‘Politics’ line, before he went to Freiburg University with a Alexander-von-Humboldt fellowship. In August 2014 he finished his Habilitation, on Cicero's Philippics, and in September 2014 Schaffenrath succeeded Stefan Tilg as director of the LBI for Neolatin Studies.

https://neolatin.lbg.ac.at/team/florian-schaffenrath- Dr Paul White, Dept of Classics, University of Leeds

I work on Neo-Latin poetry, commentaries and print culture, with a primary focus on the French sixteenth century. In relation to baroque Latinity, there are two strands to my current research: one concerns the vogue for adoxographical works in praise of ‘nothing’ written in response to Jean Passerat’s De nihilo; the other is a larger project on Neo-Latin love elegy collections, part of which focuses on the relation between this genre and mannerism and baroque in vernacular lyric.I have published articles on poetry, education, authorship and print culture in Latin and French vernacular contexts, and am the author of books on the early modern reception of Ovid’s Heroides (Ohio State University Press, 2009), on the classical editions and commentaries of the Paris-based printer and author Jodocus Badius Ascensius (OUP, 2013), and on the reception of the elegist Gaius Cornelius Gallus in the Renaissance (Routledge, 2019).

https://ahc.leeds.ac.uk/languages/staff/1237/dr-paul-white

Research Themes

- Research Themes

Baroque (c. 1580–c. 1720) is important as the earliest aesthetic – and cultural – movement to have global impact since it was spread through dynastic ambition, mercantilism, and missionary fervour. Latin, as a supranational language, played a major role in propagating this style. In literature, Baroque was characterized by rhetorical devices, especially through exaggerated forms such as paradoxes, anachronisms, antitheses, and oxymora that roused the emotions and engaged the senses. Interfacing with vernacular literature, the Neo-Latin literature of the seventeenth century contributed not only to the development of drama, but to the rise of the novel, as well as to the evolution of more traditional forms such as the epic and the epigram. Beyond belles lettres, Latin supplied lyrics to musical compositions of the time and was employed in the visual arts. In politics, Latin served as the language of treatises and contracts; in religion, it furthered the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation. It became the language of international scientific communication, used to announce and explain new discoveries. The ability to write in the common European language of scholarship was an indicator of educational achievement in an age when rhetorical and grammatical competence was demanded.

Our network, Baroque Latinity, aims to engage with the current revival of Baroque studies by addressing Baroque both as a literary style, one that distorted the norms based on the Greeks and Romans that had been systematized in the Renaissance, and as an artistic period, a complex stage in the development of post-Renaissance classicism.

During our workshops, we will address the following major questions:

1. How does writing in Latin relate to the concept of the Baroque?

2. Is there a unity to be found in the corpus of Neo-Latin texts that spans the close of the Renaissance and the emergence of the Neo-Classical age?

3. How can we describe the technical and aesthetic sophistication of Baroque Latinity?

4. How is Latin used to express the new ideas of the Baroque era – in politics, commerce, science, and art; and, what role does Latin play in the functioning of the new international intellectual movements of the time?

5. How successful is Latin at maintaining its dominance as an international language during the Baroque period – both within and outside of Europe?

Baroque Latinity - Topics

- Baroque Science: A discussion of the book by Ofer Gal and Raz Chen-Morris (Chicago University Press, 2013)

David McOmish

University of Edinburg/University of GlasgowAlthough it was first published in 2013, Baroque Science by Ofer Gal and Raz Chen-Morris continues to generate lively debate amongst historians of science. The book (or project – the book under review was a product of a series of funded projects and workshops at the University of Sydney) attempts to show that some of the major developments of the new sciences in the seventeenth century are inextricably linked to broader, contemporary baroque culture. Gal and Chen-Morris argue that this culture is characterised by an increasing lack of confidence in human senses and a self-aware, imperfect reliance upon abstraction and imagination. A particular focus of the book is upon emphasising the tensions that arose among a series of prominent actors when considering these limitations. In Gal and Chen-Morris' account of these actors (especially Kepler, Galileo, and Descartes), a shattered sense of confidence in the efficacy of human perception brings a paradoxical mix of, and an increasing confidence in the ability of the imagination to approach an approximation of external reality. The alienation from former certainties of Aristotelian reasoning and the truth of human sense perception, which the book demonstrates is found in Baroque art, is likewise found in science and philosophy. Despite its focus upon a limited number of authors and works, the book constructs a compelling interpretation and explanation of an especially significant intellectual development. In doing so, it lays the groundwork for, and encourages future scholarly activity.

Kepler and Newton bookend the temporal framework within which Gal and Chen-Morris' Baroque Science takes place. However, their account is not a simple chronological narrative of the rise of the new science in the seventeenth century. Chen-Morris and Gal divide the book into three main areas: observation (pp. 1-114); mathematization (pp. 115-230); and passions (pp. 231-82). These sections provide the interpretative lens through which both authors trace the outlines of the development of ideas across the period. The change in the way human sight was understood is the compelling story at the centre of the observation section of the book. Kepler is introduced as the game-changing figure in this regard, in his work on optics. Much has been said about Kepler's optics, but Gal and Chen-Morris present a fresh, clear-sighted understanding of how the new optical theories affected contemporaries who had been raised on the old Aristotelian theories of human sensory functions. The instrumentalisation and naturalisation of the eye, the construction of analogous, artificial aids to its function (telescopes, microscopes) all contribute in Gal and Chen-Morris' account to a collapse in confidence in the interpretative powers of the unmediated eye. The response of key actors to this challenge is at the heart of this work and at the heart of its definition of 'baroque' science. The mathematisation of nature in this context represents a necessary attempt to enforce an abstract template onto a messy natural world, whose parameters we fail to understand – as opposed to using mathematics to recognise with precision the reality of nature (pace Galileo's maxim on the laws of nature written in mathematical language). The final chapter then follows naturally, with an exploration of how Descartes understood the role of imagination in this post-Aristotelian world. The intellectual incompatibility of 'dead-end' neo-Stoic wisdom and the inquisitiveness and uncertain path of the New Sciences are highlighted to reveal the challenge that the baroque posed (pp. 272-73). Imagination becomes a ladder out of the pit of extreme scepticism in the face of knowledge of sensory limitations and an untameable (mathematically) nature. Anyone who has spent a considerable part of their time with Latin writers from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century will instantly recognise and understand the universe Gal and Chen-Morris describe here. The cohabitation in one mind of wisdom-based and observation-based data, unresolved and in opposition, yet both clearly understood, is a defining characteristic of seventeenth-century Latin literature.

This debate is particularly relevant to our own efforts on the Baroque Latinity project. It provides an important framework to apprehend and evaluate when considering the broader literary world of seventeenth-century Latin Literature of which the works of Baroque Science are a part. Chen-Morris and Gal lay useful foundations for development. One of the limitations of the book, which the authors themselves acknowledge, is the focus upon a narrow canon of works and authors. However, this limitation offers opportunity for development. It offers an opportunity to re-examine many of the familiar texts (Somnium, Sidereus Nuncius, Ptolemaic and Copernican Commentaries, and so on) of this period with a renewed baroque emphasis on choice of genre, recurring terms, lexical evolution, and other linguistic and literary conventions. More significantly, this book should be understood as a siren call to use those conventions to examine the 'vast sleeping tomes' (Frances A. Yates, ‘The Hermetic Tradition in the Renaissance’, in Art, Science, and History in the Renaissance, pp. 255-74. at 272), which explain what gave rise to and what followed from the work of Kepler, Galileo, and Newton.

This final consideration takes us back to an ongoing discussion within our project group: to what extent can we trace some of the more prominent literary and stylistic developments of 'Baroque Latinity' back to the key transformative phenomena shaping discourse in the quickly evolving intellectual culture of seventeenth-century Europe (and its expanding political and geographical horizons)? What does Kepler's Somnium share in common with Vermeer's art (Gal and Chen-Morris use Vermeer's work as the art analogue, pp. 1-7)? Can the literary, intellectual, and artistic common ground be reasonably attributed to a shared Baroque culture? If so, how? Moving beyond value judgements of good and bad literature/art/science, towards an understanding of the manner in which their shared intellectual conceptions were created is the path that Gal and Chen-Morris suggest is one well worth taking. It is true that the book's focus is upon the happy few who are now well known, but they clearly set out a template that can be reused. A renewed research focus upon the underlying linguistic mechanics of scientific knowledge in this specific and well-defined episteme, located firmly within a Latin context, is a clear desideratum. Baroque literature's expansive bookshelves present the Latinist with incredible opportunities to develop Gal and Chen-Morris' work. As well as the direct route to comparison, there is the dialectical route, with a focus upon the antecedent influences, and the possibility to discern real intellectual and related literary development. Yates' above comments in relation to Kepler, Newton, and Galileo were focused upon this discursive, dialectical, and formative relationship between new texts and their immediate antecedents. Take, for example, the commentary tradition in the medieval schools, which existed as a cornerstone of the generic canon of scholastic literature. In form, these commentaries change little over a considerable period of time. Many of the same 'authority' authors and texts persist into this Baroque period. However, the choice of core text, the changing nature of its authority, the lexical evolutions of its textual semina, the repeated occurrence of key phrases and terms, and the influence of their generic conventions upon knowledge formation are products of the cultural environment in which they were formed. A Baroque Latinity focus provides a great opportunity to bring some further definition to the intellectual culture whose beginning and progress Gal and Chen-Morris discuss.

- The Jesuit Latin 'baroque'

The term ‘baroque’ was originally applied to the artistic commissions of the Jesuits, to a style characterized by movement, drama, grandeur and opulence, one that sought to evoke emotions of surprise and awe to inspire and confirm Catholic piety. It has of course come to be associated more broadly with all sorts of literature from the seventeenth century that has little to do with the Jesuits, at least directly, with texts ranging from the sensational and ostentatious to the ingenious and puzzling, from culteranismo to conceptismo. [1] What might ‘baroque’ mean specifically in the context of Jesuit Latinity? Writers of the Society of Jesus produced plenty of neo-Latin poetry and prose from the late sixteenth to late eighteenth centuries that might be variously described as florid, sentimental, histrionic, or – choose your baroque poison! — arch and ‘argutial’. But does rhetoricality or theatricality, compression or wit, or a self-conscious anti-classicism define the Jesuit Latin baroque? Is a finer categorization possible or necessary? To play Devil’s advocate, does it make sense to speak of Jesuit Latin ‘(neo-)classicism’, ‘mannerism’ or ‘rococo’?

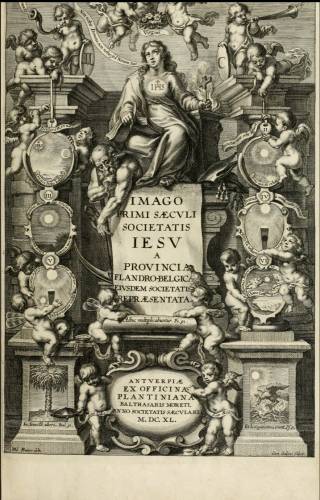

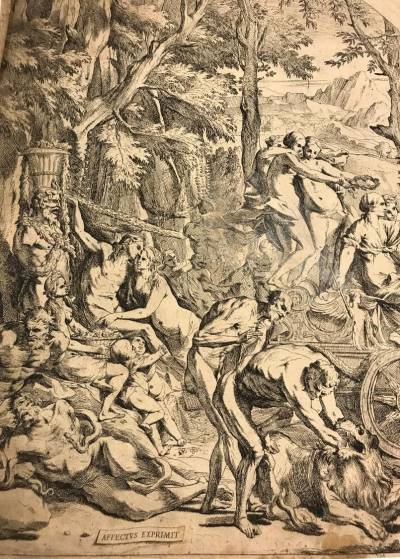

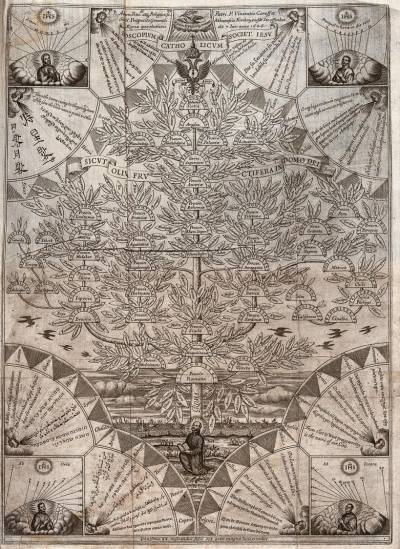

There are dangers in the periodization of Jesuit neo-Latinity, and certainly in the facile pairing of literary and artistic styles, and yet the order’s close collaboration with prominent baroque artists, engravers and architects is not without significance. Bernini and Rubens immediately spring to mind but we can also point to the Society’s enthusiastic exploitation of the Renaissance genre of the emblem book. The imagery of their 100th-anniversary Imago primi saeculi, published in Antwerp in 1640, fits the ‘baroque’ bill well enough: elaborate, organic cartouches frame curious scenes of nature and art featuring industrious putti. Marc Fumaroli has read this magnificent folio as a virtual space, inviting the imaginative reconstruction by the reader of a temple with six chapels, overlaid on a drama in five acts on the life of the Society. The exuberance, abundance and apparent boastfulness of the Imago left it wide open for attack by the Augustinian ‘Messieurs’ of Port Royal, and the Jesuits’ ‘Asianic’ Neo-Latin became the foil for a vernacular ‘Atticism’ that prided itself on Gallic simplicity and humility (in the prose of de Sacy and Pascal, for example). [2]

The Latin prose of the Imago is the work of many hands. The collective (anonymous) authors plead haste in bringing the volume together in time for the order’s birthday party, and the ‘lengthy and even overwhelming prose texts in all six books are intertwined with numerous rhetorical and poetical exercises: exercitationes oratoriae, encomiastic poetry, elegies, ludi poetici, and, at the end of each section, a number of emblems’.[3] To the Jansenists, no doubt, epideictic rhetoric gone mad! But what of the gently riddling, mostly elegiac, poems that accompany the engravings – Sidronius Hosschius and Jacobus Wallius seem to have been responsible for these -- are they baroque? There is a playful cleverness here, to be sure, but one that is undergirded by a restrained classical elegance. And while the poems may be appreciated at face value, as Putnam has shown, the intertextuality with classical poets is by no means superficial. There are direct references to Virgil, Horace, and Ovid in the mottoes, and allusions primarily to Virgil, Catullus, and Propertius in the verses.[4]

Would it be possible to classify as ‘baroque’, then, that Jesuit Latin in which we find a concentration of silver Latin (and post-classical) models? The Paciecidos libri xii (1640) by the Portuguese Bartolomeu Pereira, on the martyrdom in Nagasaki of his heroic relative, Francesco Pacheco, was published in the same year as the Imago primi saeculi. Like most Jesuit epic it is constructed on a bedrock of Virgil, but the walls of its twelve books are stuccoed over with marvels, monsters, personified virtues and vices, and gods of the East Asian as well as Roman pantheon. Literary influences range from Lucan and Prudentius through to the vernacular Camões. Yet Pereira’s literary eclecticism, if not his extravagance, is foreshadowed in at least one late Renaissance Jesuit epic, Francesco Benci’s Quinque martyres (Rome 1592), on the five Jesuits martyred at Cuncolim, Southern India, in 1586, a ‘Virgilian’ poem liberally daubed with Lucretius, Lucan and Juvencus, Vida and Fracastoro. And if later eighteenth-century Jesuit Latinists were, on the whole, more chastely classical, perhaps less inclined to mix and match literary models than, e.g., the Milanese mathematician Tommaso Ceva, in his Lucretian-Horatian satire-cum-didactic Philosophia novo-antiqua (1704), we can still find traces of post-classical, neo-Latin, and even vernacular authors in the didactic and epic poetry of suppressed Jesuits José Manuel Peramás, Rafael Landivar and Emmanuel de Azevedo.

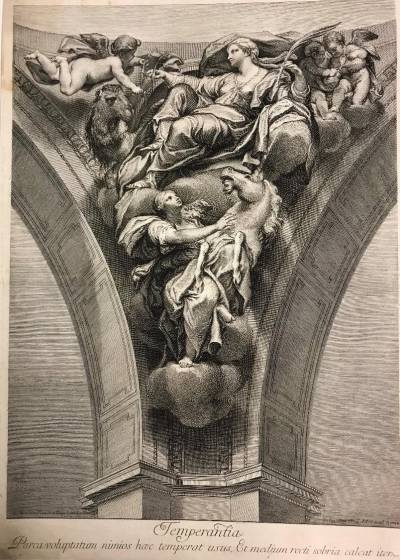

‘Art born from art’ (rather than nature) is one way to think about literary as well as artistic mannerism. Ernst Curtius preferred the term ‘mannerist’ to describe literature of any and all historical periods featuring a ‘thousand forms of unnaturalness’.[5] But ‘unnatural’ seems to me too reductive a description of the literary practice of the greatest Jesuit Latin writers of the seventeenth century -- Jeremias Drexel (1581-1638), Jakob Bidermann (1578-1639), Herman Hugo (1588-1629), Casimir Sarbievius (1595-1640), Jakob Balde (1604-1668) Jakob Masen (1606-1681), and Tommaso Ceva (1648-1737) -- however much they drew attention to literary (and literal) art, tied knots in their classical intertexts, and shuttled between allegory and history, word play and world. So... is it baroque? When Praz writes lyrically, even rapturously, about a ‘seventeenth-century frame of mind’, to explore and redeem the much-maligned poetry of Richard Crashaw, he is also implicitly redeeming the ‘baroque’ from the clutches of ‘mannerism’ and ‘Marinism’. If the Seicento traded, on the one hand, in symbols, conceits, ambiguities, and formal mannerisms it could be transported, too – says Praz -- in spiritual ecstasies, such as that of (Bernini’s) St Teresa, and stirred by profound emotion. Praz’s intincts are aesthetic and belletristic, however, and I think we lose sight of what is distinctive in Jesuit Latinity if we judge it solely in these terms, let alone against the standards of contemporary visual art.[6]

I’m not saying that Jesuits weren’t influenced by, and probably even more, influenced international literary trends in the Seicento. The craze for agudeza was fanned by writers such as Emmanuele Tesauro and Baltazar Gracian.[7] And ‘baroque’ is a convenient descriptor for some of the more sumptuous specimens of seventeenth-century Jesuit Latin writing. The didactic poetry and prose of the Neapolitan Jesuits Niccolò Giannettasio, Francesco Eulalio Savastano and Tommaso Strozzi is studded with exotic flora and fauna, marvellous ekphrases and epyllia, and infused with poetic sugar and chocolate.[8] In his De mentis potu sive de cocolatis opificio, Strozzi, for example, celebrates the posthumous union of chocolate tree and vanilla nymph in these sensual, if not erotic, verses:

Illam languiduli circum zephyrique jocantesque

Aurillae allambunt, dulcique per oscula furto,

Fragrantem rapiunt animam, vectamque volucri

Remigio alarum vicina per avia fundunt.

Hanc tenera arcano Cacai virgula suctu

Haurit, & extinctae illecebras, ac munera Nymphae

Agnoscens, laeto vegetat sua germina succo.

The languid little zephyrs and playful breezelets lick her, and with these sweet stolen kisses snatch her fragrant soul, and with the swift oarage of wings carry and pour it over the fields nearby. A tender little twig of Cacao drinks her in suck, and recognizing the charms and favours nymph, quickens his buds with happy sap.

If Strozzi’s style sometimes borders on the tasteless, it is never insipid![9]

Perhaps the greatest seventeenth-century Jesuit dramatist, Jakob Bidermann, in his epic on the massacre of Bethlehem, Herodiados libri iii,[10] presents us with a pathetic scene of frustrated filial piety which is as macabre as anything in Marino’s Strage:

Mater

An moritura taces? Ne ad Haemum respicis? Haemus

Hîc tuus, Haemus ego. Genitrix mea, negligis Haemum?

Audiit illa Haemi iam paenè emortua nomen,

Atque oblita sui, solito de more parabat

Stringere complexu venientem. At brachia nusquam

Quae collo inijcerentur, erant. Iterumque retentat,

Atque iterum truncos humeros orbata lacertis,

Ac manibus defecta movet. Tum denique solos

Omnibus e membris sibi sensit Elysa relictos

Semianimis oculos: Hos illa reclusit ad Haemi

Nomen, & adspecto satiata recondidit Haemo.

“Mother, or are you silent because you are about to die? And do you not see your Haemus? Here is your Haemus. I am your Haemus. Mother who bore me, do you not know your Haemus?” She, now almost dead, heard the name of Haemus, and forgetting herself, she prepared tightly to embrace him as he approached. But arms that could be cast around his neck were nowhere. And again she tries, and again she shrugs her maimed shoulders, lacking forearms and hands. Then, at last, Elysa perceives that, of all her organs, only her semi-conscious eyes remain: and she opens these at the name of Haemus, and closes them, content with the sight of Haemus”. (Book 1, §47)

The Germans Bidermann, Balde, Drexel, Bisselius and Masen look ‘baroque’ from any angle, and were virtuosic and versatile writers across a range of genres, from poetry and plays to novels. Masen produced a series of textbooks on poetic and prose composition and on the ars nova argutiarum. But I would like to suggest that teaching is the real key to this literature, one that opens more doors to Jesuit Latinity (let alone spirituality) than ‘baroque’. In the above passage from Bidermann, the didactic repetition of ‘Haemus’ (nomen-omen), and the faint recollections of the failed embraces of Orpheus and Eurydice and Venus and Aeneas, have all the hallmarks of an exemplary school exercise, no doubt designed to appeal to an audience of boys in the ‘Humanities’ or ‘Rhetoric’ class who were familiar with the Virgilian intertexts.[11] In my forthcoming book, Jesuits at Play: Latin Poetry and Team Spirit in the Early Modern Society of Jesus, I am exploring the ‘ludic’ elements of early modern Jesuit education and culture, elements which infuse the literary productions of the Society from Foundation to Suppression.[12]

© Yasmin Haskell

Cassamarca Chair of Latin Humanism

University of Western Australia, Perth

[1] Louis Martz and more recently e.g. Anthony Raspa have argued for the influence of Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises on English Renaissance poets of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. See below on Mario Praz’s reading of Richard Crashaw’s verse in the light of contemporary Jesuit Latin.

[2] ‘Classicism and the Baroque: The Imago primi saeculi and Its Detractors’, in Art, Controversy and the Jesuits: The Imago Primi Saeculi (1640), ed. John W. O’Malley, S.J. (Philadelphia: St Joseph’s University Press, 2015), pp. 57-88.

[3] Marc Van Vaeck, Toon Van Hoodt and Lien Roggen, ‘The Imago primi saeculi Societatis Iesu as Emblematic Self-Presentation and Commitment, in Art, Controversy and the Jesuits, 127-410, at p. 127.

[4] ‘Introductions to the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew Poetry’, in Art, Controversy and the Jesuits, 411-22, at 411-14.

[5] European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton 1953; new edition 1990), 282.

[6] Praz condemns Marino for being Italian (!), ‘hampered by tradition (to be an Italian poet meant being a Tuscan poet), being himself a refiner of the far-fetched compliments of the Petrarchan school, rather than a revolutionary, could be baroque only half-heartedly. The yoke of tradition weighed less heavily on the painters…’ (p. 252). Crashaw, however, is compared in his better moments to Rubens, Murillo and El Greco.

[7] Praz elicits many convincing connections between Crashaw’s in poetry and that of Jesuit epigrammatists and lyricists from Sarbiewski to Cabilliau.

[8] Giannettasio’s poetry is accompanied by glorious engravings by the baroque artist, Francesco Solimena.

[9] Later he will describe the delivery of a cup of restorative chocolate to St Rose of Lima by her guardian angel, in terms which are simultaneously erotic and suggestive of the mass: ‘she eagerly immerses her mouth and whole mind into the wounds of the betrothed, and drawing deep, sucks the sweetness and life from the Deity, by which she lulls the seethings of her mind and the fever, and her limbs’ (suffixi in vulnera sponsi / Os animumque omnem vivax demergit; & alto / Delicias haustu, vitamque e Numine sugit: / Queis animi, febrisque aestus, ac membra soporat; 1689, 71).

[10] Published 1622 but composed at the turn of the century.

[11] In fact the poem was dedicated to the seven-year-old Prince Philip William, Elector Palatine. See further Y. Haskell, ‘Child Murder and Child’s Play: The Emotions of Children in Jakob Bidermann’s epic on the Massacre of the Innocents (Herodiados libri iii, 1622), International Journal of the Classical Tradition 20 (2013): 83-100.

[12] For a foretaste, see my ‘Latinitas Iesu: Neo-Latin Writing and the Literary-Emotional Communities of the Old Society of Jesus’, in Oxford Handbook of the Jesuits, ed. Ines Zupanov.

- Milton, 'Elegia Tertia': a Baroque Latin Poem?

Milton, ‘Elegia Tertia’: a baroque Latin poem?

by Sarah Knight

Milton wrote the sixty-eight lines of ‘Elegia Tertia’ as a Cambridge undergraduate, to mark the death of the famous scholar, preacher, translator and bishop Lancelot Andrewes (1555-1626). Andrewes is framed as the speaker’s priority amidst several other upsetting preoccupations: ‘[a]t te praecipue luxi dignissime praesul’ (but mainly I mourned for you, most worthy of bishops; line 13). I first wrote about the poem in an essay published nearly a decade ago, but was conscious of reading it differently in 2020 for two reasons. First, for the purpose of the April ‘Learned Baroque’ workshop, I was considering whether Milton’s Latin exemplifies particular figurative and rhetorical qualities that might be called ‘baroque’, weighing the value of over a century’s-worth of art historical scholarship on this aesthetic category, in particular, against the awareness that Milton and his contemporaries would not have recognised the category themselves.

The second reason for reading the poem differently in 2020 was that although I had suggested ‘Elegia Tertia’ as a text for discussion long before Covid-19 had spread, I remembered on re-reading that it starts with an outbreak of plague. Andrewes’ death is first mentioned thirteen lines after an account of the 1625-26 epidemic in which his brothers Thomas and Nicholas had died, and epidemics also affected the poem’s author several times during his life: as a Cambridge student; when plague struck again a decade later; and in his last decade, when he stayed during the ‘Great Plague’ of 1665-66 with his wife and family in Chalfont St. Giles. A Londoner, like Milton, Andrewes was buried in St. Saviour’s Church, now Southwark Cathedral, and given the context, it seemed appropriate that during the workshop, St. Giles Cripplegate, where Milton is buried, was distantly visible in the background of a colleague’s computer screen.

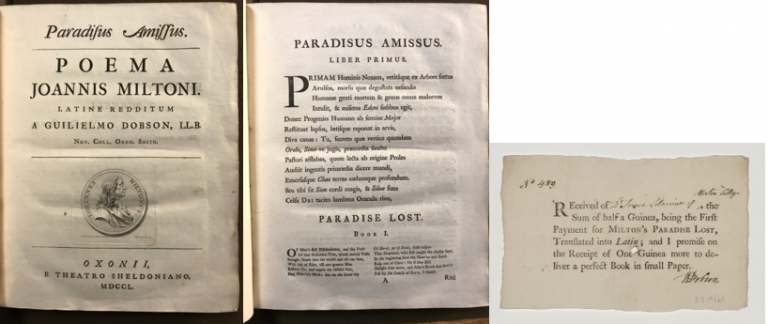

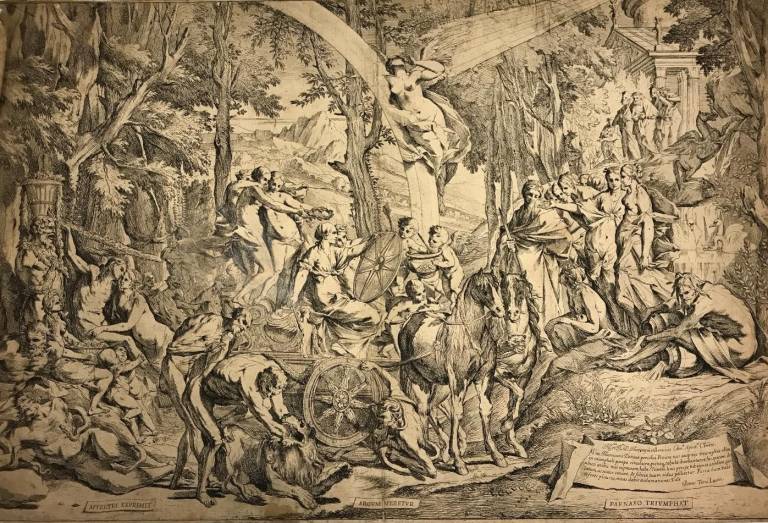

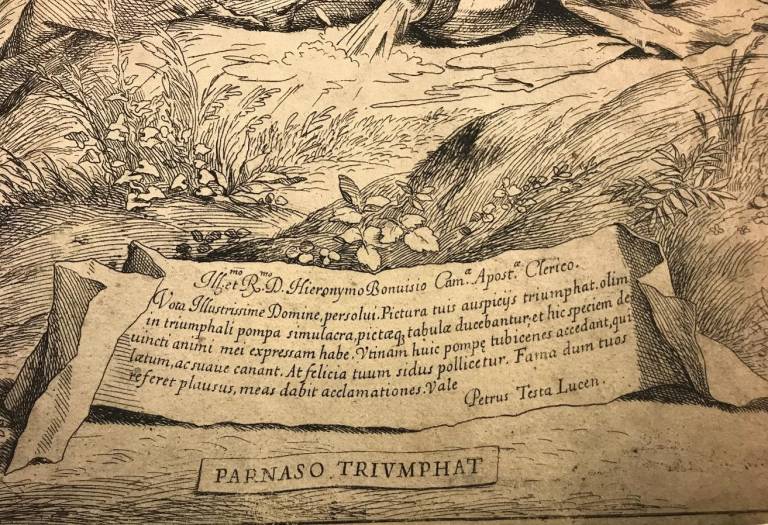

Most discussions of Milton and the baroque have tended to concentrate on the English poetry, especially Paradise Lost (1667). E.M.W. Tillyard, who, with his wife Phyllis, had edited and translated much of Milton’s student Latin writing, compared Milton in 1938 to ‘Rubens, that other great neo-classic exuberant of the seventeenth century’. Tillyard found an illustrative example in Book 6, when the angels ‘[m]ain promontories flung, which in the air/Came shadowing’ upon the ‘rebel host’ (lines 639-656), which he describes as ‘reminding of a great baroque painting’. In Milton and the Baroque (1980), too, Murray Royston argues that the war in heaven is ‘a solemnly conceived scene of immense vigour and turmoil, a baroque clash of forces such as Rubens would have delighted to paint’. Falling chronologically between Tillyard and Royston, one of the few scholars to consider Milton’s Latin writing in terms of baroque aesthetics is M.M. Mahood, who cites ‘Elegia Tertia’ in her Poetry and Humanism (1950). For Mahood, though, the painterly comparison is with an image of ecclesiastical apotheosis rather than epic confrontation: ‘Milton’s vision of Lancelot Andrewes’s triumphal entry into the roseate light and rose-scented air of a vinous heaven might, translated into tempera, adorn the cupola of any baroque church’. Mahood’s note cites lines 51-64 of the poem, where the speaker dreams of Andrewes being welcomed by ‘the heavenly host, who clap their jewel-studded wings’ ([a]gmina gemmatis plaudunt caelestia pennis; line 59), in a lush multi-sensory vision in which sight, sound and fragrance are all evoked. The speaker instructs us here to ‘See’ (Ecce; line 53) with him the vision of the bishop of Winchester (praesul Wintonius). If we imagine how a ‘great baroque painting’ or painter would render the ‘starry brightness that gleamed on [Andrewes’] radiant face’ (Sydereum nitido fulsit in ore iubar; l. 54), the Rubens comparison here might be with a painting like the ‘Apotheosis of James I’ (c. 1632-4) on the ceiling of the Banqueting House at Whitehall, in which a thin nimbus of light, not quite a halo, surrounds the King’s white-grey hair, as he looks upwards towards a red-and-gold crown.

Royston points to the war in heaven in the English epic as the ‘baroque clash of forces such as Rubens would have delighted to paint’, but lines 9-12 of ‘Elegia Tertia’ also depict a brutal conflict in ‘Belgia’ (line 12) that Rubens in fact did go on to paint a few years after working on the Whitehall Stuart apotheosis. Milton’s subtitle, ‘In obitum Praesulis Wintonenis’ (On the death of the bishop of Winchester), makes explicit the poem’s commemoration of the loss of a famous individual, but the first part of the poem depicts more widespread fatalities caused by disease – the 1625-26 plague – and war. Ryan Hackenbracht has argued that several of these elements help to establish what he calls the poem’s ‘apocalyptic tone’. The art historian Gauvin Alexander Bailey has argued that ‘[b]aroque art was born out of calamity’, citing the many seventeenth-century outbreaks of plague and the Thirty Years War as particularly significant crises for its development. Milton’s poem represents just one of many outbreaks across Europe in that decade that were also captured, sometimes directly, sometimes allegorically, by contemporary painters including Poussin (e.g. ‘The Plague at Ashdod’, 1630) and Van Dyck, working in Sicily when the plague struck (see, for instance, his 1624 ‘Saint Rosalie Interceding for the Plague-stricken of Palermo’). The account of the plague in ‘Elegia Tertia’ is followed by the description of deaths of ‘lost leaders’ (amissos . . . duces; line 12) and ‘heroes’ (heroum; line 11) for whom ‘all Belgia wept’ ([f]levit . . . tota Belgia; line 12) in the earlier stages of the Thirty Years War (1618-48). Rubens depicted this conflict in his great allegorical painting ‘Consequences of War’ (1637-38), commissioned by Ferdinando II de’ Medici for the Palazzo Pitti in Florence. Milton’s poem individualises death in war, not least by representing these losses as personally affecting for the speaker: he cannot stop thinking about them, as we see from the repetition of the plangent verb ‘memini’ (I remembered) at lines 8 and 11. In a more abstract, allegorized manner, however, Rubens uses figurative art to show how war impedes art. Surrounded by other mythological and agonized human figures, including a Fury with her blazing torch, Mars crushes a book underfoot.

An intensely visual poem, ‘Elegia Tertia’ begins with a command to notice the speaker’s sadness and to look at the ‘imago’ (image) of what has caused it. Even if the spectacle is only present in the speaker’s imagination, this ‘imago’ and the emotions it has provoked are presented as inseparable. The first two words of the poem are ‘[m]oestus eram’ (I was grieving), and the speaker’s solitude heightens this feeling: he is ‘sitting silently’ (tacitus. . . sedebam), ‘without any company’ (nullo comitante; line 1), ‘and with many sad things clinging to [his] mind’ ([h]aerebantque animo tristia plura meo; line 2). We have seen how, when the vision of Andrewes first appears, the speaker commands the reader to ‘see’ (ecce; line 53), and at the very start, too, we are told to ‘look’ (en; line 3) with him at an ‘image of deadly catastrophe’ (funestae cladis imago) that has ‘suddenly arisen’ ([p]rotinus . . . subiit), an ‘imago’ that Libitina, the Italian goddess of funerals and corpses, has ‘made on English soil’ ([f]ecit in Angliaco . . . solo; line 4). The picture Milton prompts the reader to contemplate is of both Libitina and ‘dira mors’ (line 6), an early version of the ‘Grim Death’ Satan meets at the gates of hell at the end of Book 2 of Paradise Lost. This ‘dira mors’ is a social leveller calling the tune of its own danse macabre, having ‘entered the towers of princes’ (procerum ingressa est. . . turres; line 5) and ‘beaten down walls heavy with gold and jasper’ (pulsavit . . . auro gravidos et iaspide muros; line 7). Although critical discussions of Milton and the baroque have tended to focus on Paradise Lost, we find in this early Latin poem as well two of baroque art’s most characteristic aspects: suffering bodies graphically imagined, and the representation of an afterlife in richly idealised terms.

Further reading:

Gauvin Alexander Bailey. Baroque and Rococo. London: Phaidon. 2012. Quotation from page 33.

Sheila Barker. ‘Poussin, Plague, and Early Modern Medicine’. Art Bulletin 86.4 (2004): 659-689.

Gordon Campbell and Thomas N. Corns. John Milton: Life, Work, and Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2008.

Roland Mushat Frye. Milton’s Imagery and the Visual Arts: Iconographic Tradition in the Epic Poems. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Ryan J. Hackenbracht. ‘The Plague of 1625-26, Apocalyptic Anticipation, and Milton’s Elegy III’. Studies in Philology 108.3 (2011): 403-438. Quotation from p. 427.

Sarah Knight, ‘Juvenes Ornatissimi: The Student Writing of George Herbert and John Milton’. In Neo-Latin Poetry in the British Isles, ed. by Luke Houghton and Gesine Manuwald. London: Bloomsbury Academic/Bristol Classical Press, 2012. Pp. 51-68.

M.M. Mahood. Poetry and Humanism. London: Cape. 1950. Quotation from page 203.

P.E. McCullough. ‘Andrewes, Lancelot (1555-1625), bishop of Winchester’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. January 2008.

Murray Royston. Milton and the Baroque. London: Macmillan. 1980. Quotation from page 119.

Xavier F. Solomon. Van Dyck in Sicily 1624-1625: Painting and the Plague. London: Silvana. 2012.

E.M.W. Tillyard. The Miltonic Setting, Past and Present. London: Chatto & Windus. 1938. Quotations from page 70 and 100.

- Baroque Rome in Maffeo Barberini's Verse Letter to Lorenzo Magalotti

Baroque Rome in Maffeo Barberini's Verse Letter to Lorenzo Magalotti

by

Stephen Harrison

Fellow and Tutor in Classics, Corpus Christi College, Oxford

Professor of Latin Literature, University of Oxford

Maffeo Barberini (1568-1644, Pope Urban VIII 1623-44) was a talented Latin poet whose verse was collected and widely published before and (especially) during his pontificate. He was also a central figure of Roman Baroque culture, painted by Caravaggio as a young cleric and later patron to Bernini during his papacy; he first favoured and then condemned Galileo and the poet Marino. One of the most attractive of his poems is a 147-hexameter epistle of the period 1609-11 (when Barberini was already a cardinal and bishop) to his friend Lorenzo Magalotti (1584-1637). Magalotti was then serving in the papal Curia as referendary of the Tribunals of the Apostolic Signatura (i.e. as a canon lawyer concerned with papal petitions), was later appointed as Urban’s own Cardinal Secretary of State (1623-28), and ended his career as bishop of Ferrara (1628-37).

The poem is framed as an invitation by Barberini to his friend to leave behind the business of the Curia in Rome and come for relaxation to the papal estate at Castel Gandolfo in the Alban Hills 25 km south-east of Rome, the site of the ancient city of Alba Longa. This estate was acquired by Clement VIII in 1596; Urban himself as Pope was later to convert the castle there into the extant papal palace, until recently a summer retreat for Popes and now a museum, with magnificent gardens and spectacular views over Rome and Lazio.

The poem looks back to Augustan Rome, combining a number of recognisably Horatian features (the hexameter epistle format, the invitation to a friend in high office to relax, the commendation of the country) with further classical frameworks. But it also focuses firmly on Baroque Rome, especially in lines 78-90 (my translation):

Quam iuuat intuitu magnas discernere moles

Urbis! Ab Esquiliis celsa testudine culmen

Porrigit eximii species miranda sacelli, 80

Quod tibi, Christi parens, almi lux prima pudoris,

Addictum posuit studium pietasque dicauit.

Qua coluit puroque colit te pectore Paulus:

Cuius opus pulchro surgens in colle Quirini

Se domus extollit, regali condita sumptu. 85

Excelsi tholus en templi se proximus infert

Sideribus, pia quod vasto molimine cura

Pontificum struxit Petro. Te Paule loquetur

Posteritas, laudemque tuis hanc laudibus addet:

Nam tibi debetur tantae pars maxima molis. 90

[What a pleasure it is to make out with one’s gaze the great masses

Of the city! From the Esquiline the wondrous appearance of the outstanding shrine

Stretches out its tower with its interlocking roof,

Which was established for you, mother of Christ, first luminary of motherly chastity,

By faithful devotion, and dedicated by piety, with which Paul

Has worshipped you and worships you now in his pure heart;

Whose own work, his House, projects itself high, rising

On the fair Quirinal hill, founded with funding on a royal scale.

Nearby the dome of the lofty Church enters the view, so close to the stars,

Which the pious care of the popes has built with vast effort for Peter.

Posterity will speak of you, Paul, and will add this praise to your praises:

For such a great part of this great mass is owed to you.]

In these lines we see the view of the city of Rome from Castel Gandolfo with its emphasis on the recent and current building projects of Pope Paul V (Camillio Borghese, 1550-1621, pope 1605-21). The stress on Paul’s worship at the papal basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore on the Esquiline (80-4) alludes to the current construction there (1606-1612) by Flaminio Porzio of Paul’s Borghese Chapel, while the reference to the house on the Quirinal (85-6) points to the papal Palazzo Qurinale, begun by Gregory XIII in 1583 and being extended by Porzio for Paul at the time of writing, and the description of St Peter’s (89-90) marks Paul’s extensive works there, including Carlo Maderno’s massive main façade with Paul’s huge and still prominent building inscription of 1612.

This commendation of the current papal building programme understandably praises the master of both the poem’s author and its addressee; but this praise too has classical affinities, echoing the poet Statius’ praise of the emperor Domitian’s Roman monuments in the late first century CE and the lauding of Augustus’ extensive buildings in the city in the contemporary poems of Virgil, Horace, Propertius and Ovid. Here we see Paul V represented as both following and outdoing the Roman emperors; it is no accident that in an earlier line (61) the pope is presented as princeps, evoking one of the key pagan imperial titles, just as pontifex maximus, the emperor’s title as formal head of the state religion, was then as now the key formal Latin designation of the pope’s own office. The imperial dwellings and pagan temples erected by the Roman rulers of antiquity are here implicitly outdone by the modern works of the Christian sovereign of Rome, something which Barberini himself would later continue in his own papacy.

[This blog draws on work in progress on Urban’s Latin poetry]

Further Reading

Maphaei S.R.E.Card.Barberini nunc Urbani Papae VIII Poemata (Paris, Typographia Regia: 1642).

P.Rietbergen, Power and religion in baroque Rome. Barberini cultural policies (Leiden-Boston: 2006) 95-142.

- Poems and Pipelines: Latin Verse on the Fountains in and around Baroque Rome

Poems and Pipelines:

Latin Verse on the Fountains in and round Baroque Rome

by Paul Gwynne

Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Studies at The American University of Rome

Throughout the sixteenth century a number of leading Italian clerics vied with each other in the creation of sumptuous villas and gardens in and around Rome. The sprawling ruins littering the Roman campagna inspired them to emulate the magnificent building projects of ancient Rome.(1) From their readings in the classical authors, and particularly in the descriptions of villa life in the letters of Cicero and Pliny and the verse of Horace, Virgil and Statius, these cardinals knew that water, ‘splashing into fountains or dripping into dank grottoes amid groves of plane trees’ was an essential feature of these estates.(2) With the rediscovery in 1429 of a manuscript of Frontinus, De aquis, interest in the ancient aqueduct system was revived and, slowly but surely, the piecemeal restoration of the ancient waterways began.(3) In 1560s Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este (1509-1572) dammed the river Aniene near the famous cascades to provide sufficient pressure for the water gardens he was planning at Tivoli; contemporaneously Cardinal Alessandro Farnese (1520-1589) diverted the Aquae Tepula and Julia to bring water to Grottaferrata; in addition, he realised a water regulation system for Lago di Vico which irrigated the surrounding land and fed the fountains of his country retreat at Caprarola. Just as the Roman poet Statius (45-96 CE) had offered panegyrics on the hydraulics of the villa of Manlius Vopiscus at Tibur (Silva, 1.3) or the baths of Claudius Etruscus on the Quirinal (Silva, 1.5), so the court poets of these ‘Renaissance princes of the Church’ lauded contemporary achievements. For example, the sixteenth-century Brescian poet Lorenzo Gambara (c. 1500-1586) published the following verses on a grotto with fountain at the Villa Rufina (now Falconieri), erected c. 1550 high in the hills above Frascati:

IN FONTEM ALEXANDRI RVFINI EPISCOPI MELPHIENSIS IN AGRO TVSCVLANO

Rupe sub hac vaga lympha fui sine nomine, sed nunc

Rufina e domini nomine lympha vocor.

Ille etenim sparsos latices collegit, et undas

Auxit, et extructo fornice clausit aquas. (4)

[ON THE FOUNTAIN OF ALESSANDRO RUFFINI, BISHOP OF MELFI, IN THE FIELDS OF FRASCATI. Beneath this rock, I was once a wandering stream without a name; but now I am named Rufina water after my master; for that illustrious man collected the scattered springs, increased their flow and, when a vault had been constructed, enclosed the waters.]

Poems on fountains belong to a virtually unbroken tradition which stretches back to the compilation of The Greek Anthology and form a distinct genre with its own tropes and vocabulary. Despite their rhetoric, these poems can supply a wealth of information for the water historian. For example, here Gambara’s verses allude to the hydraulic works undertaken by Alessandro Ruffini, Bishop of Melfi (ob. 1579). In 1549 the enterprising bishop obtained the privilege to drain the swamps of the Val di Chiana in the Papal States; the work, undertaken intermittently throughout the 1550s, was successfully brought to a conclusion in 1560 by the celebrated engineer, architect and mathematician Rafaello Bombelli (1526-1573). Presumably, Bombelli was also responsible for the supply of water to the grotto at Villa La Rufina celebrated here in this elegiac quatrain. Indeed, the verse accurately records the water mechanics, albeit obliquely. The water was collected in a large cistern which fed the grotto fountain via two channels (‘I was once a wandering stream et cetera’). Although the fountain grotto fell into disrepair during the extensive refashioning of the Villa in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, an inscription of Gambara’s poem still survives (now placed above the entrance to the ruined grotto) and provides and enduring monument to this lost world. (5)

GROTTAFERRATA

In the same anthology Lorenzo Gambara also published a verse description of the Farnese palace at Caprarola in 1000 hexameters with a dedication to his patron Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, known to his contemporaries as Il Gran Cardinale. This poem was thoroughly revised and considerably lengthened to 1500 lines and republished twelve years later in 1581 in a separate edition but with the same dedication. Both versions of the poem are panegyrics on the Farnese family, and Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in particular, under the guise of a celebration of the family’s country retreat 58 kilometres north of Rome at Caprarola. We should also note that in addition to the epyllion on Caprarola there are twelve epigrams on the various fountains that the cardinal constructed at his country retreat both at Caprarola and at Grottaferrata. Here are two examples in different meters on the fountain at Grottaferrata:

IN FONTEM CRYPTAE FERRATAE.

SEPTENOS peteret colles cum Iulia lympha,

Quos vetus intortis Albula scindit aquis:

Capta loci insignis forma est, beneolentis et horti,

Et rupis, platani quam levis umbra tegit.

Dixit et, hic mihi certa domus: vos tecta valete

Regia: cumque tuo Thybride Roma vale.

[ON THE FOUNTAIN AT GROTTAFERRATA. When the water-nymph Iulia was heading towards the seven hills, which ancient Albula cleaves in its twisting stream, she was captivated by the beauty of this remarkable place and the perfumed garden, which the gentle shade of a plane tree and rocky cliff shields, and said, ‘This is certainly my home; farewell royal halls, and farewell Rome and your Tiber’.]

Aliud.

Florentes rigat hos hortos aqua Iulia, nec non

Tepula, quae quondam peterent cum celsa Quirini

Moenia, et alluerent septem, ceu flumina, colles,

Erravere diu iam saevo a milite fractis

Fornicibus, has per valles, nemorumque recessus.

At postquam in partem sedes haec regia cessit

FARNESIO, cum Romanam non posset ad urbem,

Ad patriosque lares dulces perducere lymphas;

Hoc rarum construxit opus, geminosque reduxit

In liquidum hunc fontem latices, hortosque locumque

Pictura ornatum, signisque, et marmore, et auro,

Silvarum nymphis una cum fonte dicavit. (6)

[Another. The Aqua Julia waters these flowering gardens, and the Tepula, which once sought the lofty walls of Rome and washed against the seven hills like a river; when the arches had been broken by a savage army, these waters long wandered across these valleys and through woodland haunts. Then this royal seat came into the possession of Farnese; since he could not bring these sweet waters to the city of Rome he led them to their ancestral home; he built this rare work, and brought back twin streams into this fountain, and dedicated both the gardens and place decorated with colourful marble and statues and gold, together with the fountain, to the woodland nymphs.]

When Cardinal Alessandro Farnese took possession of the dilapidated Abbey of Grottaferrata in 1564, one of his first acts was to restore the aqueduct and the water supply to the abbey and build a new fountain in the abbey’s grounds, with designs probably supplied by the architect Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola (1507-1573), who was working almost exclusively for the cardinal at this date and was charged with even the most minor architectural commissions. (7)

The source of the Aqua Julia had originally been tapped by Agrippa and merged with the Aqua Tepula in a new conduit somewhere near the twelfth milestone of the Via Latina; that is, not far from Grottaferrata. Farnese revisited Agrippa’s original project. Thus in his patronage of the abbey we see Alessandro Farnese presenting himself as heir to Agrippa. The poet similarly presents the Cardinal restoring the damage done by the heathen invaders in the dark ages; albeit in idyllic pastoral mode.

THE POET

Very little is known about our author, Lorenzo Gambara (Laurentius Gambara).(8) What little is known of his life can be summarized as follows. Gambara was born at Brescia, probably in the early decades of the sixteenth century, although the exact date of his birth is unknown. After graduating from the University of Padua he transferred to Rome where he entered the service first of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, and later of Pope Gregory XIII Boncompagni (1572-1585). He died in 1586. Mention in the correspondence of intellectuals of the stature of Fulvio Orsini (1529-1600), Paolo Manuzio (1512-1574) and Annibale Caro (1507-1566) attests to his participation in the highest academic circles across the Italian peninsula. He was a prolific poet and translator, his interest focusing primarily upon pastoral. He translated Bion and Moschus from Greek into Latin verse and made a free verse translation of Longus’s prose romance Daphnis and Chloe. His fame today, however, rests largely upon his ‘brief epic’, four books on Christopher Columbus’s first voyage to the Americas: De navigatione Christophori Columbi, first published in 1581 and again (with dramatic revisions), in 1583 and 1585 and 1586.

THE POEM CAPRAROLA

Gambara’s poem Caprarola recounts the visit to Rome by two Sicilian shepherds; their tour of the Farnese properties in the city and subsequent expedition to Caprarola. This itinerary is a thinly-veiled excuse to celebrate Farnese magnificence. The narrative is simple. Having seen the Farnese sites of Rome, the travellers decide to visit Caprarola where they arrive at sunset and discover Cardinal Alessandro Farnese himself (in pastoral guise as the head gardener Lycormas), creating a bower around the Aegocrene fount.

Mox superant placidum collem, Tuscumque Lycormam

Texentem inveniunt frondosa umbracula fontem,

Fontem Aegocrenes circum, rigidaque secantem

Silvestres serra truncos, scissisque flagella

Summa immittentem foecunda ex arbore ramis,

Insita ut e proprio trunco, tunc fertilis arbos

Ignotas frondes, ignotaque poma sub auras

Efferret, decora hortorum, silvaeque virentis. (9)

[They soon climb the gentle hill and discover Tuscan Lycormas weaving a leafy arbour around a fountain, the Aegocrene, and cutting forest logs with a hard saw and grafting fecund vine-shoots into the branches cut from lofty treetops, so that having been implanted from their own trunk, then a fertile tree would bear unknown branches and unknown fruits under the breezes, the glory of the garden and green forest.]

The Greek title Aegocrene (Αἰγόκρήνης) translates, somewhat prosaically, into English as the ‘Fountain of the Goat’ and alludes to the fanciful etymology of the town and villa: ‘Caprarola’ (capra meaning ‘goat’ in Italian). The ‘goat fountain’ formed the centrepiece of the new gardens. (10) It was situated to the north of the palace in the area of woodland rising up the hillside behind the villa (near where the Palazzina would later be constructed). Erected in 1562, the fountain had as its focus a terracotta statue of the she-goat Amalthea, who suckled the infant Jupiter, concealed from his father in the Greek island of Crete. According to different versions of the myth she was later transformed into the constellation Capricorn and her horns became the fabled ‘cornucopia’, or ‘horns of plenty’. The statue was surrounded by putti whom the goat suckled, her ‘milk’ being the water of the fountain. The name recalls the Hippocrene (‘Fountain of the Horse’) on Mount Helicon, sprung from a blow from the hoof of the mythological horse Pegasus, and the source of all poetic inspiration. An epigram by Gambara combines these various elements:

IN FONTES HORTORVM CAPRAROLAE EPIGRAMMA

Quum folia haec inter iaculatur Capra liquores,

Atque Irim vario lympha colore refert.

Non mirum, hanc caelo sidus pluviale locavit

Iuppiter, et pluvias fundere posse dedit. (11)

[EPIGRAMS ON THE FOUNTAINS OF THE GARDENS AT CAPRAROLA. When the nanny-goat spurts water amid these leaves, the water also renders a rainbow in myriad hues. Little wonder, Jupiter placed her as a rainy constellation in the heavens, and granted her the ability to pour forth the rains.]

Although Farnese’s ‘goat fountain’ was clearly intended to rival the Hippocrene fountain of Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este’s new villa and gardens at Tivoli, the iconography of the fountain was probably inspired by Cicero who wrote to his friend Atticus, asking him to describe his rustic shrine to the nymph Amalthea so Cicero might copy it on his own country estate south-east of Rome, at Arpinum. (12)

The idea of poetic inspiration from water is taken up in the tour of the gardens. This begins with lunch at the so-called Fountain of Aphrodite adjacent to the Summer Garden:

His visis, linquunt auro radiantia tecta;

Ad viridesque hortos accliuo tramite tendunt. [...]

Et sese sistunt alto sub fornice fontis:

Hic ubi iam Leuce panem, generosaque vina

Addiderat mensis, atque hoedi integra ferebat

Uiscera, fumantesque epulas: tum lance patenti

Apponit lac concretum, post fraga, favumque

Mopsopii mellis: comites dehinc fonte nitenti

Saepe manus, saepe ora lavant; mirantur et ipsam

Marmoream effigiem latices effundere ad auras,

Haud aliter quam flumen aquae loca saxea subter

Delabens montis, cum valles venit ad imas,

Visceribus terrae latices prorumpit ad auras,

Diuersosque suo gignit de gurgite riuos.

Inde alacres dapibus fontis vescuntur ad undam;

Atque epulas inter vario sermone fruuntur. (13)

[When they had toured the apartments, they exit the gleaming halls and head up a sloping path toward the gardens in bloom. […] And they stop in their tracks under the fountain’s high vault. Here Leuce had placed bread and wines of noble stock upon the table and brought them the complete innards of a kid and hot food; then she places clotted milk in a wide dish, with wild strawberries on top, and Mopsopian honeycomb; the companions then wash their hands and faces in the clear fountain and marvel at the marble image spurting water into the air; as when a stream gushing down a stony mountainside, flows into deep valleys, the waters burst into the air from deep inside the earth and the spring gives birth to different rivers from its source. They then dine eagerly by the fountain side and enjoy their repast amid varied conversations.]

While the tourists dine at the fountain, they are entertained by a song, a long interlude in 47 elegiac couplets (94 verses), on the various fountains situated across the gardens. I cite a section from the opening:

DVM te muneribus tantis FARNESIVS heros,

Et te tam largo munere donat aquae:

Quid tibi fons animi est? num te felicior alter?

Num te Castalii laetior vnda fluit?

Praecipue dum Roma potens te inuisit, et omnis

Ausonia, atque omnis Gallia, et Hesperia.

Miraturque nouos fructus, atque aurea poma,

Et virides hortos, quos tua lympha rigat;

Et varios latices, et te pulcherrime, qui tam

Sub gelido nitidas fornice claudis aquas.

Haec loca erant olim saxosis aspera dumis;

Et nunc sunt pictis aurea porticibus.

Et qua custodes fluuiorum et faucibus vndas

In stagna effundunt dulcia, tophus erat.

Hic vbi nunc Dryadum rorantia cernitis antra,

Cliuosum ornabant marmora nulla locum.

His olim arebant incultis collibus herbae,

Nullaque de celsa rupe cadebat aqua.

Et qua nunc per stagna natant fluitantia pisces,

Abrupti moles saxea montis erat.

Quaque suis Capra vberibus diffundit in auras

Tot liquidos latices, scrupea silua fuit.

Imposuitque suo nomen de nomine monti:

Ex eodem pagus nomine nomen habet.

Tergemini infantes hic simae colla iacentis

Prensant, et palmis vbera plena premunt.

Hinc lympha exiliens frondes ferit ictibus altas,

Lambit et aetherei lucida signa poli.

Et quoties quatiunt frondosa cacumina lymphae

Effusae, quamuis sit sine nube dies;

Apparet toties vario perfusa colore

Insidens Iris frondibus arboreis.

Hanc circum foliis strepitant, caueisque salignis,

Et canere hos latices velle videntur aues.

Te non est fons lucidior, nec pulchrior vllus:

Iam cedat rutila Lydius Hermus aqua. (14)

[While the Farnese hero presents you with such great gifts and presents you with such a generous gift of water, what do you think, fountain? Is there another more blessed than you? Do the waters of the Castilian spring flow more plentiful? Especially while powerful Rome visits you and all Italy, all France and the west. They marvel at the new fruits, and golden apples and the lush gardens which your waters irrigate; and various fountains, and beautiful you, who enclose the clear waters with a cool arch. These places were once rough with prickly bushes, but now they gleam with painted porticoes. There was once tufa where the guardians of the fountains pour water into sweet pools. Marble did not decorate the steep place where now you see the Dryads’ damp haunts. The plants were thirsty in these uncultivated hills and no water cascaded from the lofty crag. Where fish now swim through flowing ponds, there used to be the stony mass of an excavated mountain. And where the nanny goat now shoots these clear waters from her udders into the air, there was once a forest composed of jagged rocks; and she gave her name to this mountain and the village also is named after her. Snub-nosed triplets hanging round her neck grasp and press the full udders with their hands. Jets of water spurting forth strike the high branches and wash the bright constellations of the heavenly sky and whenever these jets of water shake the leafy roof, although there is no cloud in the sky, a rainbow lying in wait among the leafy trees appears drenched in all the different colours. Birds chirp amid the leaves around this fountain and in a wicker enclosure, and seem to want these waters to sing. No fountain is more limpid than you, none more beautiful; and Lydian Hermus with its golden stream now gives place.]

For the Sicilian visitors the Farnese properties present a series of never-ending marvels. The poet notes the natural phenomenon of the multi-coloured rainbow refracted from the cascading waters. The fountains not only provide cool respite from the summer’s heat, but its waters also surpass the fabled rivers of antiquity, such as the gold-bearing river Hermus of Aeolis. Examples can be multiplied as the party continue their exploration of the estate.

These few examples should remind us that the Italian Renaissance Garden was just as complex in its iconographical programme, as the decoration of the interior of the villa which it surrounds and accompanies. The vogue for neo-Latin poetry made these estates vivid and real for a wide reading public across Europe (and beyond) and still allows a rare glimpse into this lost world; if channelled into the water historians’ documentary field this verse can also provide a deep and unexpected pool of shimmering delights.

NOTES

1 Ribouillault 2019 367-386.

2 Coffin 1991 28-57; 29.

3 Rinne 2019 324-341.

4 Gambara 1569 120.

5 Cogotti 2018 25-27.

6 Gambara 1581 58-59.

7 Robertson 1992 171.

8 Asor Rosa 1999 53-54.

9 Gambara 1581 14.

10 Romana Liserre 2008 73-86.

11 Gambara 1569 38.

12 Cic. Att. 1.16.

13 Gambara 1581 38-39.

14 Gambara 1581 40-41.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Asor Rosa, A. 1999: ‘Lorenzo Gambara’, Dizionario Biografico Italiano, 52, 53-54.

Coffin, D. 1979: The Villa in the Life of Renaissance Rome, Princeton University Press.

Coffin, D. 1991: Gardens and Gardening in Papal Rome, Princeton University Press.

Cogotti, M. 2018: Villa Rufina Falconieri a Frascati: Il Gardino, Gangemi.

Colalucci, F. 2013: ‘Il Quirinale di Ippolito D’Este: ricostruzioni virtuali e reali’ in Marina Cogotti and Francesco Paolo Fiore (eds), Ippolito II D’Este: cardinal, principe, mecenate, De Luca, 139-162.

Facies, S. 1571: In fontes Caprarolae Alexandri Farnesii cardinalis, Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale, MS VE60.

Gambara, L. 1569: Poemata, Antwerp: Christopher Plantin.

Gambara, L. 1581: Caprarola, Rome: Francesco Zanetti.

Ribouillault, D. 2019: ‘The Cultural Landscape of the Villa in Early Modern Rome’ in Pamela M. Jones, Barbara Wisch and Simon Ditchfield (eds), A Companion to Early Modern Rome, Brill, 367-386.

Rinne, K. 2019: ‘Renovatio Aquae: Aqueducts, Fountains, and the Tiber River in Early Modern Rome’, in Pamela M. Jones, Barbara Wisch and Simon Ditchfield (eds), A Companion to Early Modern Rome, Brill, 324-341.

Robertson, C. 1992: ‘Il Gran Cardinale’: Alessandro Farnese, Patron of the Arts, Yale University Press.

Romana Liserre, F. 2008: Grotte e Ninfei nel ‘500. Il modello dei giardini di Caprarola, Gangemi.

- Epidemic, Saint, and Epic Poetry: Verse Hagiography in the Baroque Period

Epidemic, Saint, and Epic Poetry: Verse Hagiography in the Baroque Period

by Patryk Ryczkowski

Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen, Bereich Gräzistik / Latinistik

Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck

In a time of the crisis, such as the Covid-19 pandemic that we are facing nowadays, Latin poetry can be of most instructive value. One illuminating example is the Hagiopoea (1611) by the French author Sébastien Rouillard, a hagiographic epic in three books devoted entirely to Carlo Borromeo (1538–1584), the archbishop of Milan (from 1564). As the city was confronted with a plague disease, he provided his people with moral support – regardless of his own health, he offered himself to gain the indulgence for their sins and thus to overcome the epidemic:

Ac quamquam graveolens inter diapasmata virus

Corrugare solet nares et mixta sereno,

Sancte Pater, possunt offendere nubila coelo

Totque inter festas geniali schemate pompas

Vix forte illius sit amoena recensio cladis,

Quam meminisse subit stomachum lymphaticus horror,

Et turbare piget tristi haec solemnia luctu,

Attamen et nobis prosunt quod Numinis irae

Et quod in his steterit potior victoria Carli,

Ipsius haec liceat suffire piamina lauris.

Iam sexagenum sextum mediaverat annum

Phoebus, ad Erigones furias sua spicula vibrans,

Cum (tolerante Deo) dira seu morte luendum

Tunc ultura nefas, Carli aut visura triumphos,

Exciit Alecto Furiarum e gurgite pestem. [...]

Cum Mediolani video te Carle frequentes

Ducere per vicos ambacti examina cleri [...]

Suppetiasque Dei queribunda voce rogantem:

Parce devs, miserere devs, iam parce popello –

Sons ego, solus ego tantorum (heu!) causa malorum:

Ah, peccata luam solus! […] (Seb. Roll. Hag., p. 74–75, 77).