Embryonic cells sense stiffness in order to form the face reveals Roberto Mayor in Nature article

8 December 2021

Cells in the developing embryo can sense the stiffness of other cells around them, which is key to them moving together to form the face and skull, finds a new study published in Nature by CDB's Professor Roberto Mayor and Dr Adam Shellard.

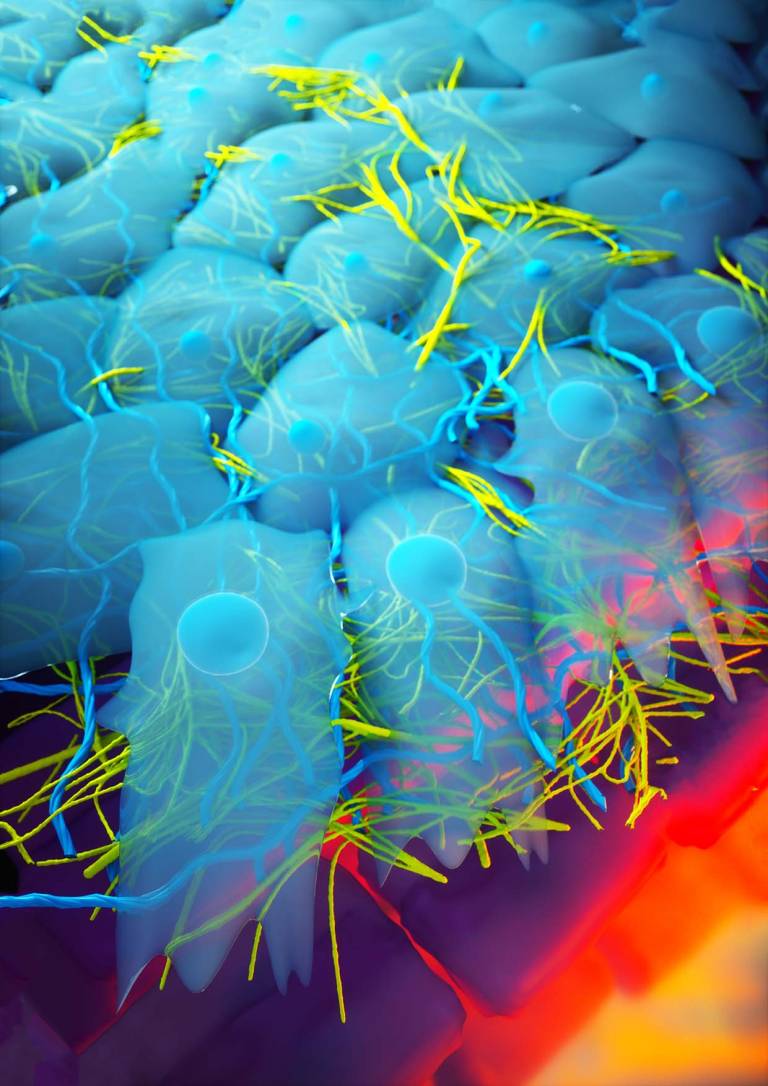

Chemotaxis, the process by which cells move along a gradient of chemical signals, is the main mechanism to explain directional migration. In this paper, Professor Roberto Mayor (UCL Cell & Developmental Biology) and colleagues show that an additional mechanism called durotaxis is also involved in driving direction migration of neural crest cells in vivo. Durotaxis is the process by which cells follow a gradient of mechanical stiffness, and their data show that the same migrating neural crest cells self-generate a stiffness gradient of front of them. In addition, they identify the mechanism by which chemotaxis synergizes with durotaxis to drive efficient directional cells migration.

Co-author Dr Adam Shellard (UCL Cell & Developmental Biology) said, “this newly identified behaviour is likely to be found not only in the cells that form our face, but in the cells that forms all our organs, and could play a central role in the dissemination of cancer cells during metastasis which hijack the behaviour. Understanding how these cells move is an important step toward developing therapies for craniofacial malformations and cancer progression.”

The study was supported by the Medical Research Council, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, and the Wellcome Trust.

Links

- Shellard A and Mayor R. (2021). “Collective durotaxis along a self-generated stiffness gradient in vivo”. Nature

- Prof Roberto Mayor's lab page

Image

- Illustration of neural crest (shown in blue) on a substrate. Credit: Ella Maru Studio/Mayor lab

Close

Close