Climate research in the time of COVID-19 – and funding cuts

16 July 2021

The Green Recovery

We’re fighting on two fronts – the immediate battle against COVID-19, to limit its impacts on health and on people’s livelihoods; and the ongoing battle to cut global emissions and limit the impacts of climate change.

World leaders, including President Biden and Prime Minister Johnson, while trying to deal with the impacts of COVID-19 at home, have set out ambitious emissions reduction targets, and expressed support for a “green recovery” from the pandemic. They argue that this will create jobs and prosperity for their countries. But, just like COVID-19, climate change is a global challenge that requires collective action to ensure that no-one is left behind; after all, no-one will be safe until we’re all safe.

The “green recovery” is a hopeful idea in these difficult times. It is just as important to low and middle income countries as it is to richer countries like the UK and the US. In our research, we’re examining whether a green recovery could become a reality in Zambia and Ghana. Both Zambia and Ghana have ambitions, as stated in their development plans and policies, to be prosperous with diverse, resilient and sustainable economies. Both countries are also dealing with significant challenges.

In Zambia, the economy has been badly hit by COVID-19 and the effects of supply chain disruption, including on the mining sector which is a major contributor to the economy. COVID-19 cases are rising sharply again, and significant numbers of the population remain unvaccinated. Meanwhile, there are fears that the onset of the pandemic may derail delivery of basic health services and exert a strain on the health care system, causing other diseases to go untreated. For example, attention to children’s health has been postponed as many health facilities have been turned into COVID-19 centres.

Ghana has also been severely affected by COVID-19, seeing an increase in debt and a collapse in jobs in informal sectors. The country’s oil extraction industry makes a significant contribution to the economy through exports, but most of the country’s energy supplies are still imported, due to the lack of refining capacity. The country’s agriculture sector is also important to the economy, but vulnerable to future impacts of climate change.

Can Zambia and Ghana achieve rapid recovery from COVID-19, whilst also putting in place the foundations of longer-term social, economic and environmental development? We’re investigating how these various objectives can be balanced, through in-depth interviews, policy analysis, workshops and modelling of the energy, economic and land use systems. Through these multiple methods, and through detailed engagement with citizens of the two countries, we aim to produce scenarios that will demonstrate how a green recovery can also achieve broad social and economic development objectives that address citizens’ concerns.

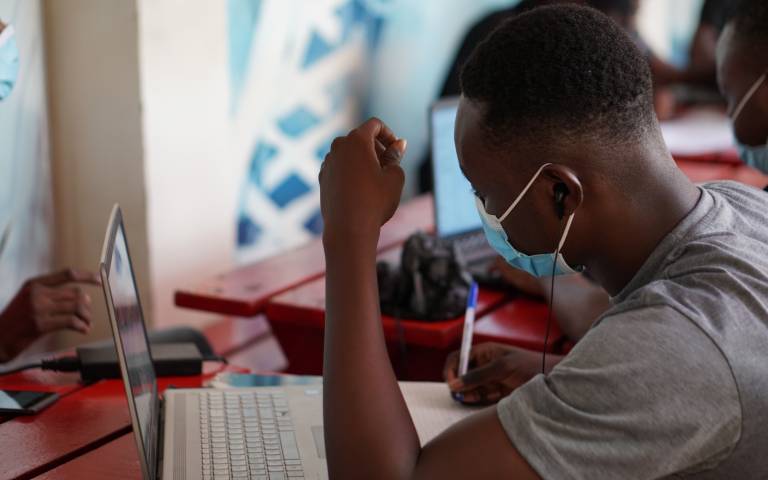

But it hasn’t been easy. Doing participatory research in a time of COVID-19 presents considerable challenges. We’re constantly having to re-think the ways in which we engage with stakeholders, in order to get that essential contact, but in a way that respects the equally essential needs for health and safety precautions to limit the spread of the virus.

And in late 2020, the UK government announced a cut in its foreign aid budget from the legally enshrined 0.7% of GDP, to 0.5%. This had a direct impact on our project – as it did on many others. For us, it translated into an overall cut in our project funding of about 45%, and of just over 60% in the current financial year. We have tried to make back what we can of this shortfall by seeking funding from other sources, and as far as possible protecting the salaries of the researchers based in Zambia and Ghana. As we strive to deliver something close to what we had hoped for with this project, it will inevitably mean that much of our work has to be delivered as unpaid overtime. But even with these efforts, the foreign aid cut will have an impact on what this project can deliver – and on how the UK is perceived as an international research partner. As long as it remains in place, the cut will diminish the achievements of future projects.

The ethics of basic human solidarity demand that we consider the needs of our neighbours as well as our own, especially during times of crisis. But maintaining a consistent position in our relations with others is also to our own benefit – for with climate, just as with COVID-19, no-one is safe until we’re all safe.

Photo by Kojo Kwarteng on Unsplash

Close

Close