How to fairly phase out fossil fuels – new research

20 May 2020

A blog by Greg Muttitt, Economics and Policy of Energy and the Environment MSc student

If the world is to achieve the ambition of the Paris climate goals, we will need every tool at our disposal. One under-used tool is limiting the extraction of fossil fuels.

Some scholars have observed significant political and economic advantages to tackling fossil fuels from the supply side. In some circumstances, policies to reduce supply may be more economically efficient than reducing demand. These approaches are starting to appear in policy too: Costa Rica, France and New Zealand have ended new oil and gas licensing, for example, and the World Bank no longer finances fossil fuel extraction.

But where and how should this tool be applied?

Our new paper in Climate Policy, which I co-authored with Sivan Kartha, tackles that question.

Our paper reviews how extraction-dependent economies and communities will be affected by energy transition, and examines how these impacts change under three common allocative approaches - economic efficiency, meeting development needs, and effort-sharing. Drawing lessons from the strengths and weaknesses of these approaches, the paper proposes five principles for equitably curbing fossil fuel extraction within climate limits.

Whereas every country has a multiplicity of sources of territorial emissions, extraction occurs in geographically specific places. Extraction is more immediately connected with the workers and local economies it supports, and conversely with fenceline communities whose lands and waters it pollutes. Two of our principles reflect this: there should be a Just Transition for workers and communities, and transition should be consistent with environmental justice.

Achieving the Paris goals requires all countries to wind down fossil fuel extraction and use. But this does not mean all must phase out at the same pace: there remains a question of how the global carbon budget and costs of meeting it should be allocated between countries.

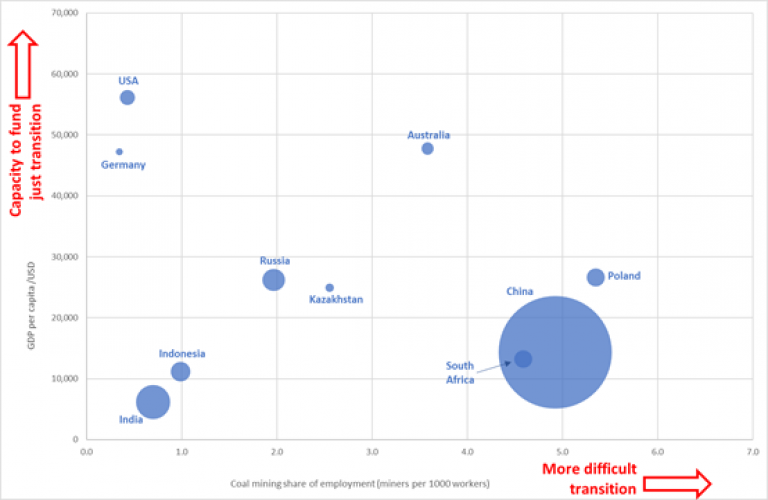

To illustrate, consider coal mining in Germany compared to China. Coal miners account for 0.03% of Germany’s workforce, compared to 0.6% of China’s. As a proportion of the national workforce, China’s challenge is thus twenty times the size of Germany’s.

Moreover, Germany’s coal mining wage bill amounts to 0.03% of GDP; China’s to 0.5%. Assuming the costs of Just Transition (such as retraining and social protection) are proportional to the wage bill, Germany has sixteen times greater economic resources than China relative to what is needed.

Germany and China thus differ along two important dimensions: the relative scale of the transition, and the countries’ ability to mitigate and absorb its adverse impacts. The graph below shows the ten largest coal-extracting countries on these two dimensions.

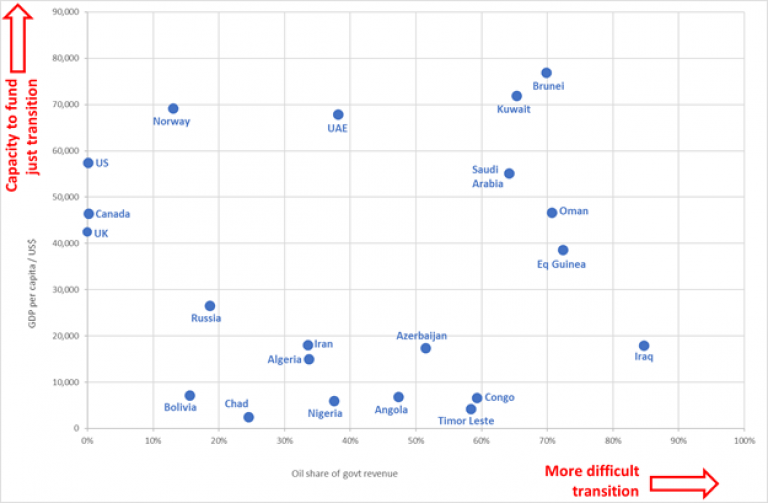

Oil and gas extraction are less labour-intensive than coal, but often provide a significant share of government revenues. Those revenues fund public sector salaries, public services and investment. Clearly, energy transition will be most difficult when dependence on those revenues is greatest. This is shown, again plotted against economic capacity, for selected oil-producing countries in the second graph, below.

To minimise the social costs, transition should proceed fastest in the wealthier economies least dependent on extraction, in the top-left of these graphs.

Even if wealthy countries phase out extraction rapidly, extraction-dependent poor countries will still face a greater challenge: restructuring their economies essentially within a generation. Financial, institutional and technological support will be vital to enable a Just Transition.

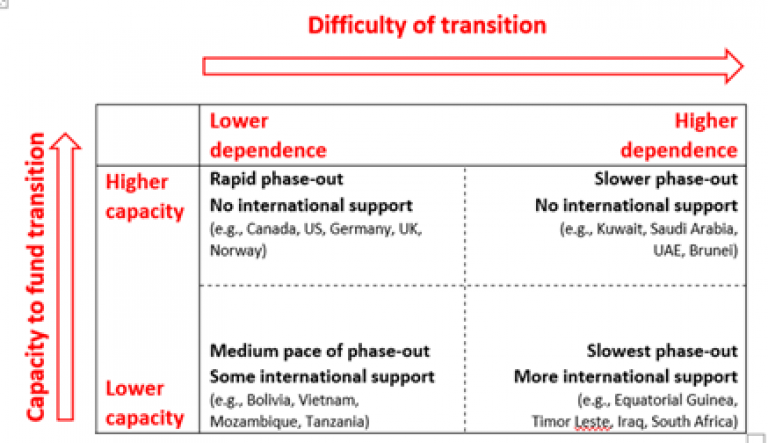

Echoing the two graphs above, our final graphic below shows what might be expected of countries in terms of speed of transition and funding.

Drawing these reflections together, we propose five principles to equitably manage the phaseout of fossil fuel extraction:

- Phase down global extraction at a pace consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C;

- Enable a Just Transition for workers and communities;

- Curb extraction consistent with environmental justice;

- Reduce extraction fastest in economies least dependent on extraction and with greatest financial resources;

- Share transition costs fairly, according to ability to bear those costs.

One immediate implication is that - in order to fairly share global efforts - wealthy countries need to move much faster than currently proposed.

There is growing interest in the role of fossil fuel extraction in climate change. With calls for a post-COVID19 stimulus to support the energy transition, and to avoid bailouts of fossil fuel companies, we hope these principles may help inform the pathway to a better, post-fossil society.

Further information

Read the paper in Climate Policy here.

Greg Muttitt is a postgraduate student at UCL, studying Economics & Policy of Energy and the Environment MSc. He was previously research director at NGO Oil Change International for five years, working on climate change and energy transition. He is author of the book Fuel on the Fire: Oil and Politics in Occupied Iraq (2011).

All views expressed in this blog are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources or University College London.

Close

Close