Written by Antonia Antrobus-Higgins

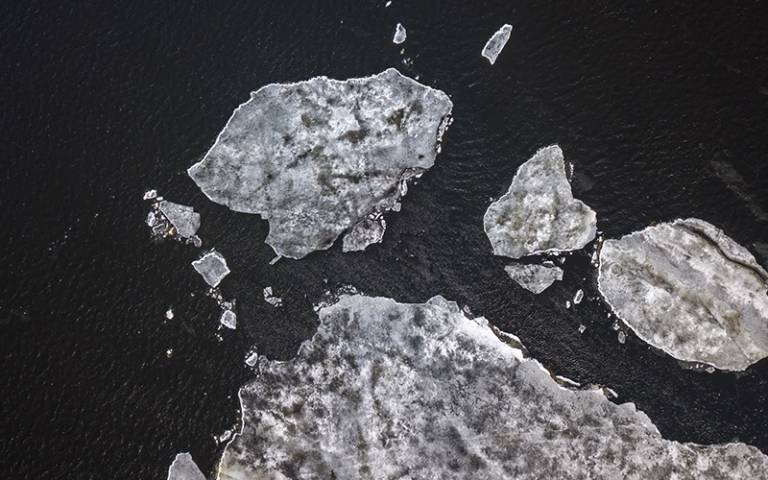

Climate change is a hot topic now. It conjures images of Extinction Rebellion protests, Greta Thunberg and polar bears. The UN Secretary General has claimed that “we face a direct existential threat.” (UN, 2018). This “direct existential threat” has meant that climate change is more centre-stage in the public consciousness than sustainable development. In contrast, the picture sustainable development paints is easily ushered off as an unattainable utopia.

However, whilst climate change action and sustainable development seems to be an ‘either-or’ decision, “the links between climate change and sustainable development are strong. Poor and developing countries, will be among those most adversely affected and least able to cope with the anticipated shocks to their social, economic and natural systems” (UN, 2019). In addition, the unsustainable model of development which allowed for the current developed countries to industrialise has significantly contributed to climate change. Therefore, it is not a question of whether the world can address both climate change and sustainable development, but rather that in doing so effectively they both should be addressed as they are inextricably linked.

In 2017, over 15,000 scientists signed an article which warned that, “to prevent widespread misery and catastrophic biodiversity loss, humanity must practice a more environmentally sustainable alternative to business as usual” (Ripple et al, 2017). This ‘business as usual’ refers to how the prioritisation of economic development has caused environmental degradation. In contrast, the United Nations defines sustainable development as, "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (WCED, 1987).

Climate change will hinder this model of development. Therefore, it was globally agreed in the Paris Agreement on Climate Change in 2015 to combat climate change, adapt to its effects and provide enhanced support to developing countries. The fact that the US withdrew from the agreement despite having the highest carbon emissions per capita, is emblematic of ‘business as usual’, as Trump, a business man, would understand.

The year 2015 was regarded as a landmark year for international cooperation as UN member countries also adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This consisted of 17 SDGs to be achieved by 2030, including SDG 13 on climate change. These international agreements were perceived as being co-dependent and having the same vision: making the world better. The model of unsustainable development has to change.

The IPCC has argued that the world should aim to limit temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. The UK has been amongst the first industrialised countries to respond to this by setting a net-zero emissions target for 2050. The IPCC claims that, “climate change has the potential to affect many aspects of human development, positively or negatively, depending on the geographic location, the economic sector, and the level of economic and social development already attained” (Parry et al, 2007, Section 7.7). Climate change will serve to increase global inequality, by disproportionately impacting less developed countries, mostly in the global south.

This is because “climate change is projected to undermine food security… exacerbate existing health threats, adversely affect water availability and supply, slow down economic growth, make poverty reduction more challenging and lead to increased displacement” of populations (Borgen, 2017). Consequently, climate change action and achieving sustainable development are co-dependent. This is articulated by Mohan Munasinghe, former Vice-Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change who says, “Climate change and sustainable development interact in a circular fashion. Climate change will have an impact on prospects for sustainable development, and in turn, alternative development paths will certainly affect future climate change” (Munasinghe, 2003).

The United Nations Development Programme says that the SDGs are “ambitious in making sure no one is left behind”. “The objective was to produce a set of universal goals that meet the urgent environmental, political and economic challenges facing our world” (UNDP, 2019). This contrasts significantly to the MDGs which focused on issues affecting certain countries, such as combatting malaria. Arguably, the increasing threat of climate change has demonstrated that all ‘developed countries’ have not developed sustainably. Therefore, there needs to be a re-stitching of the fabric of our global economies, so they function in a way that does not compromise the needs of future generations.

As national implementation of these global instruments begins, the need to ensure linkages between the SDGs and Climate Action was the centre of discussions at the Climate Change Conference in Bonn, Germany in 2019. This is because the detrimental effects of climate change constitute a major threat to achieving the SDGs. National efforts at ensuring adaptation and building resilience to climate change can only work if there is a strategy to implement the SDGs across sectors.

Climate policies, “if not properly designed can be socially and economically regressive” (Fuso Nerini et al, 2019) and could disproportionally impact certain economies and people in the short term. Therefore, the world can’t focus on achieving the SDGs without also trying to limit climate change to 1.5°C because they are not in two separate silos, but are two sides of the same coin. This is demonstrated by the fact that “15 out of 17 SDGs have one or more MoI [means of implementation] targets that enable… or reinforce… climate action” (Fuso Nerini et al, 2019).

In conclusion, it is counterproductive to think of climate change action and achieving the SDGs as separate and combative. An effective climate change policy needs to work towards achieving the SDGs and vice versa. Underlying both climate change action and the SDGs, is the simple human want to ensure that we are not compromising the needs of future generations.

References

- Borgen (2017) Climate Change and the Sustainable Development Goals. Borgen Magazine [Online] Available at: https://www.borgenmagazine.com/climate-change-and-the-sustainable-development-goals/

- Fuso Nerini, F., Sovacool, B., Hughes, N., Cozzi, L., Cosgrave, E., Howells, M., Tavoni, M., Tomei, J., Zerriffi, H. & Milligan, B. (2019) Connecting climate action with other Sustainable Development Goals, Nature Sustainability, 2, 674–680. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-019-0334-y

- Munasinghe, M. (2003) Climate Change and Sustainable Development Linkages: Points of Departure From The IPCC TAR. Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2b95/9407c0019844a6b5ee23917e562ef80e25bc.pdf

- Parry, M., Canziani, O., Palutikof, J., van der Linden P., and Hanson, C. (eds) (2007) Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2007. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. Available at: https://archive.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg2/en/ch7s7-7.html

- Ripple, W.J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T.M., Galetti, M., Alamgir, M., Crist, E., Mahmoud, M.I., Laurance, W.F. et al (2017) World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice. BioScience, 67 (12) 1026–1028. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix125

- UN (2019) Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform: Climate Change. [Online] Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/climatechange. Accessed 3rd December 2019

- UN (2018) United Nations Secretary-General: Secretary-General’s remarks on climate change (as delivered). [Online] Available at: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2018-09-10/secretary-generals-remarks-climate-change-delivered . Accessed 3rd December 2019

- UNDP (2019) Sustainable Development Goals: Background on the Goals. [Online] Available at: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals. Accessed 4th December 2019

- World Commission on Environment and Development (1987) Our Common Future. Available at: http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf

Close

Close