Corporate responsibility in a net zero UK

8 November 2021

At a glance

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in business is crucial to meet the net zero target

- Definitions both of CSR, and of actions related to it, vary between different sectors

- Campaigns aimed at shifting both corporate and consumers’ mindsets may render CSR activities a moral and ethical commitment rather than a legal responsibility

- Cooperation between local, national and international agents is crucial to define CSR activities and their impact

What is the issue?

Creating a net zero UK will require a fundamental transformation in our economy and society. Businesses will play a vital role in this, and companies are increasingly keen to signal their commitments to corporate social responsibility. Last year for instance, a record-breaking number of international corporates disclosed their greenhouse gas emissions through the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) – one of the original pioneers of climate change disclosure. The total number of companies disclosing their greenhouse gas emissions was 70% higher than the number that reported when the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015, and collectively represented over 50% of global market capitalization (CDP, 2020). Other advocates for the disclosure of climate impacts by companies, including Mark Carney (Governor of the Bank of England from 2013 to 2020) and the Climate Change Committee, argue that this process of measurement, reporting and target setting is a pre-requisite to drive business strategy and investment in more sustainable directions.

Taking action is indeed important, as government statistics tell us that business and industry are directly responsible for around 17% of greenhouse gas emissions in the UK, and clearly these need to be dramatically reduced. UK businesses, however, do not exist in isolation, being connected to each other along national and international supply chains and through financial relationships, to governments and regulations, and ultimately to us as consumers. Climate issues frequently link to other sustainability issues, further complicating any business case for action. Tracing a responsible path through this complexity can be challenging for businesses, and their plans may be met with charges of “greenwash”. Therefore, significant complexity underlies companies’ public signalling of their corporate responsibility.

In this explainer we consider the evolving meanings of corporate social responsibility (often shortened to “CSR”), discuss opportunities for businesses to reduce their climate impact directly and through their wider influence, and reflect on some of the difficulties that may be lurking behind the sustainable commitments that they make.

What are the key characteristics of the issue?

Corporate responsibility is an evolving concept

Whilst the concept of “Corporate Social Responsibility” is a reasonably modern product, the interactions between business, the natural environment and society are hardly new: business has philanthropic roots in many cultures around the world. Early pioneers, for instance, were arguing for the importance of providing good and healthy living conditions for workers in the UK at the time of the Industrial Revolution.

Environmental awareness began to rise up the agenda in 1960s in the UK, and although attention has waxed and waned, in the early 1990s John Elkington famously created the Triple Bottom Line – augmenting the traditional bottom line of businesses’ financial accounts with both environmental and social outcomes (Elkington, 1998). The idea lives on in the current dialogue around environmental, social and governance (“ESG”) metrics for companies. The advent of “ESG” has begun to transform corporate social responsibility into business accountability.

Interest in the CSR agenda has risen steadily higher over recent years. Considerable impetus has been provided in particular by the Paris Agreement adopted at COP21 in 2015, and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Both of these now appear with regularity in large- company reporting, where they are used to frame individual companies’ actions, and provide linkage between corporate actions and global sustainability goals. The UK’s national commitment to net zero has also fostered mirrored commitments from individual businesses themselves, many of whom have now set their own net zero targets.

Other standards and regulations at local and national levels are also shaping company priorities. In the UK, these include legislation on carbon pricing, building regulations, and corporate reporting requirements, many of which derive originally from our European Union membership. Voluntary schemes, product labels and industry guidelines also help to kindle business interest in CSR, such as Science Based Targets and Bankers for net zero. Furthermore, increasing engagement across civil society has seen the emergence of growing numbers of pressure groups and climate lobbyists, such as Extinction Rebellion; as well as awareness-raising activities of celebrity influencers, and of engagement in these issues of more establishment figures such as David Attenborough. This rising tide of sustainability information and interest, combined with the net zero target, suggests that larger businesses at least must increasingly view sustainability as an issue on which they need to communicate.

UK business contribution to climate change extends across our economy

Whilst corporate dialogue on sustainability is growing, substantial reductions still need to be made across all business greenhouse gas emissions. Although business emissions have fallen over recent decades, reductions are concentrated in certain sectors, notably heavy industry, and also correlate to non-climate related falls in economic activity, such as the financial crisis in 2008, and COVID. According to Government statistics, the business sector was responsible for the 17% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2019. If the UK is move to net zero these emissions must be substantially reduced, and companies must make good their net zero commitments.

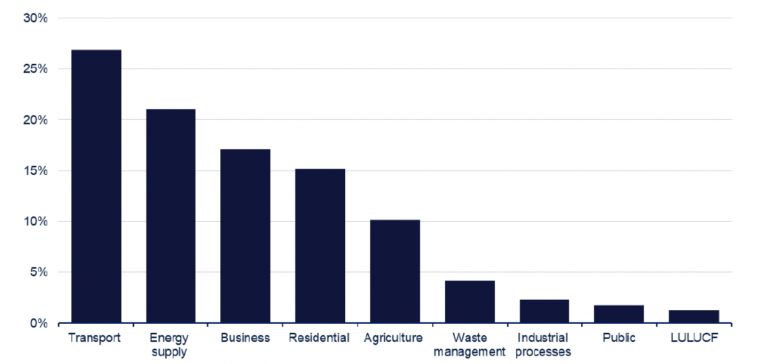

However, this simple picture obscures the interactions between greenhouse gas emissions in our economy. For instance, transport emissions lowered only by 4.6% since 1990, and represent 27% of all the greenhouse gas emissions in the UK. They include the indirect environmental impacts of those businesses who manufacture vehicles, or who make their money moving goods and passengers around the UK. Agricultural emissions arise from farming and food production related to businesses both large and small – and to our own demand as consumers for food products. Making the case for business action therefore relates to more than an individual company’s CSR initiatives, as it involves thinking strategically across the economy.

Figure 1: Territorial UK greenhouse gas emissions by NC sector, 2019 (%)

Source: BEIS (2021)

To make matters more complicated, for businesses who want to be more responsible, commitments to reduce greenhouse gases may intertwine, or even conflict, with other sustainability goals, such as employee wellbeing, local communities, fair trade with suppliers and many others. For example, the recent pandemic has led some real estate companies to suggest that increasing the flow of air through building ventilation systems intended to keep employees safe could have increased energy use in their buildings (Tomuck, 2021). Reducing climate impact and formulating a strategy will be distinct for each industry and indeed individual company, as each faces a differing constellation of these factors.

Business case for action is highly varied – and the boundaries of responsibility untested

Not all businesses are the same: on the one hand, for some heavy-emitting sectors – such as concrete, cement, iron and steel production – climate change and emissions reduction has long been a material issue. These sectors are already subject to carbon pricing, heavily exposed to energy prices, and subject to media and investor scrutiny, encouraging them to reduce their climate impacts. However, these industries will remain heavily polluting unless massive technological change and investment is implemented, such as Carbon Capture and Storage. Solutions such as these would require a massive joint commitment of business, research, finance and the government to be successfully implemented.

By contrast, consumer-facing businesses face different dynamics. Big brands may be distanced from the producers of raw materials or goods that they sell, whilst also being exposed to public scrutiny of their environmental impact. They hold powerful potential levers to incentivise consumers to switch towards more sustainable consumption and behaviours. There are opportunities, for instance, in the food and consumer goods industry, to buy into trends for organic farming, better land-use management, and meat-free and sustainable diets. However, whilst businesses may wish to position their products as ethical or “green”, gathering the data to enable this across dispersed, and often globalised, supply chains is hugely challenging.

Transport businesses provide a further contrasting example, with initiatives from companies such as UPS and DHL to move to electric vehicles for their deliveries (Dans, 2018). Businesses such as these, who are key facilitators of economic activity, are caught in a different position between businesses, employees and consumers. The question that emerges – and which is still largely unanswered – is where along the supply chain responsibility for reducing climate impacts should be allocated, and who bears the costs.

Shifting the mindset to foster change

Other industry sectors and companies, such as those attracting massive crowds and followers, could be even more effective at changing values and norms, thus acting as facilitators to pro-environmental and sustainable behaviours. A clear example is the campaign by Fiat, which, to advertise its new electric vehicles (e.g., Fiat 500), asked the movie actor Leonardo Di Caprio, who is also known for taking up environmental causes, to take part in the campaign. Fiat evidently hopes that this strategy will pay off, by drawing both on the general fame of the actor, as well as his perceived commitment to fight for the environment.

Also, the sports industry has the potential to deliver successful social sustainability messages, as shown by the concern for free school meals shown by the footballer Marcus Rashford. However, while some clubs may be noted for their green behaviour, others are clearly lagging behind (e.g., Lockwood, 2021). Encouraging sport players and professionals to front environmental campaigns could accelerate further the path towards net zero emissions. The participation of individual sport professionals could make sport clubs more sensitive to the topic and more keen to undertake sustainable behaviours. Since sports professionals can be highly influential for young people, their involvement in environmental campaigns could lead to a change in the mindset of current and future generations, eventually making CSR activities driven by intrinsic, altruistic, and ethical reasons.

The case for action is therefore spread across multiple businesses and the contribution of sectors to the net zero campaign is varied.

Can we believe the hype?

The increasing demand for more sustainable investments and the pressure to move towards net zero is itself creating a business: companies want to minimise transition risks and capitalise on new opportunities on the horizon, and this is causing a frantic search for ESG talent and expertise (O’Dwery, 2021). The creation of CSR indexes and the quantitative assessment of these activities should make the evaluation more transparent and effective and reduce the use of CSR for purely profit-seeking or reputation purposes, but without real substance. Businesses are also understandably keen to communicate these various sorts of corporate social responsibility actions as evidence of their sustainability credentials.

But should we believe what has recently been referred to as this ever increasing “sustain-a-babble” (Temple-West and Talman, 2021)? If companies make empty promises that are not backed up by action, they can be accused of “greenwashing”. Corporate greenwashing scandals, from the famous VW emissions-gate, to the recent extensive publicity around BlackRock’s ESG “whistle-blower”, reveal inconsistencies between words and actions, and critically undermine trust in business commitment to CSR.

If we are to have any hope of reaching net zero and tackling climate change in a meaningful way, business impact is going to need to move decisively towards real and verifiable impact. Tighter regulation and greater scrutiny may well be critical, as well as informed sustainability decisions. Also, while it seems clear that many industries are, to a greater or lesser extent, engaging in CSR activities, it is not clear what the driving forces of such activities are – some of them could be due more by the need to abide by the law and meet the minimum requirements imposed by new standards, than by a firm awareness and willingness to commit to transformational change in the environmental cause.

Tighter cooperation across the main actors of our society would lead to a clearer definitions and implementation of CSR activities and related concepts. There are difficult issues to solve, and although business must be held to account for its climate impact, it is also grappling with multi-dimensional issues around data, responsibility, and cost, set against a shifting landscape of policy, and uncertain trade-offs that make decision-making harder. Consequently, only a rigorous commitment of private, public, and R&D bodies can provide the legislative, executive and evaluative framework we need in order to achieve the net zero target. For instance, coordination across local, national and international bodies would help finding common definition of CSR, laws and directions to regulate its implementation; besides, the creation of tools to measure CSR activities and their impact by academics and other R&D bodies would lower the risk of greenwashing and lead to a better impact evaluation of the efforts done by the society to lower GHGs as well as of more precise forecasting related to the net zero goals and ESG: better metrics would help the industry sectors and their specialists to define their CSR targets and to measure the impact of their implementation. These actions all together should facilitate a diversified and at the same time converging approach in which CSR can play a role towards the net zero target.

References

- BEIS (2021), “2019 UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Final Figures”, BEIS Report.

- CBRE (2021) https://placetech.net/analysis/cbre-grapples-with-emissions-data-headache/

- CDP (2020), “The A List 2020”, Available from: https://www.cdp.net/en/companies/companies-scores

- Dans (2018), “Corporate Social Responsibility is turning green, and that’s a Good Thing”, Forbes, September, 14th 2018.

- Elkington, J. (1998), Cannibals With Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business, Stony Creek, CT: New Society Publishers.

- Lockwood, D. (2021) ‘How green are Premier League Clubs?, Tottenham Top Sustainability Table’, BBC, 25/01/2021, available at https://www.bbc.com/sport/football/55790760.

- O’Dwery, M. (2021), “Sustainable Investing Boom and net zero pledges drive ESG drivers war”, Financial Times, June 5 2012.

- Temple-West P. and Talman K., (2021) “The whistleblower who calls ESG a deadly distraction”. Financial Times, August 13 2021. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/4fdc6cdf-7bd6-41bc-b376-2137521e3017

- Tomusk, K. (2021).CBRE grapples with emissions data headache, PlaceTech, 8 Sep 2021. Available from: https://placetech.net/analysis/cbre-grapples-with-emissions-data-headache/

Close

Close