DPU PhD candidate successfully defends thesis on the political ecology of oil in Nigeria

3 March 2020

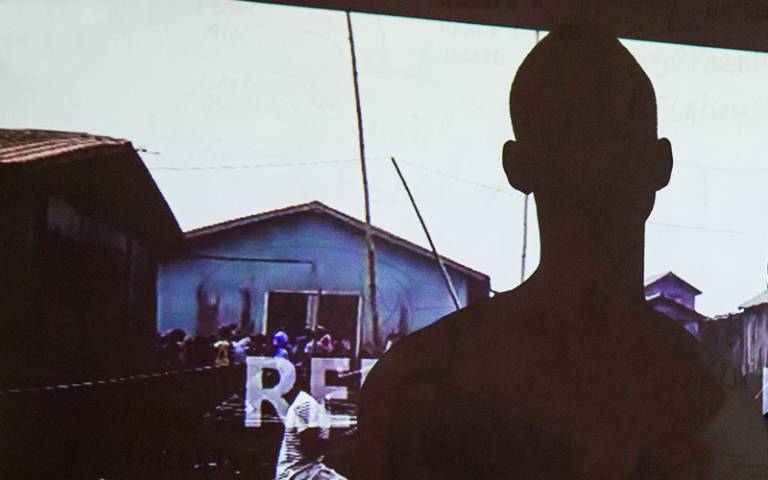

Congratulations to Modesta Alozie who has successfully defended her PhD thesis titled 'the political ecology of oil in Nigeria: understanding youth violence from the perspectives of youths'.

At her recent thesis defence, Modesta Alozie successfully argued that explanations of youth violence in the Niger Delta should shift away from analyses based on youth (mis)behaviour and move towards an analysis which locates young people’s relationships with violence within the broader social structures that contour their lives. These social structures can be traced back to the nature of the Niger Delta and the distribution of oil revenues that was institutionalised following the commercialisation of oil in Nigeria in 1958.

The Niger Delta is an oil producing region in Southern Nigeria. It is rich in biodiversity and has abundant petroleum resources. Increased demand for Nigeria’s low sulphur oil transformed Nigeria from an agrarian economy into the largest oil producer on the African continent. In 2020, oil dominates Nigeria’s exports and contributes significantly to its foreign-exchange earnings.

The commercialisation of oil in 1958 and the ways in which the Federal government introduced new institutional mechanisms set the stage for Nigeria’s fiscal centralism. These included a nationalised oil company (NNPC) established in 1971 and the Distributable Pool Account introduced in 1966, subsequently renamed the Federation Account in 1979. In contrast to the fiscal arrangement in pre-oil Nigeria, these institutional mechanisms gave the Federal government the legitimacy to retain a large proportion of the profits generated from the oil industry in the Niger Delta. But while the federal government and oil companies accumulated enormous profits from oil, violence became a part of everyday life in the Niger Delta.

To a significant degree, the linkages between oil and violence in the Niger Delta is connected to discontent over the oil revenue distribution pattern, which has led to the emergence of violent groups in which youths, and male youths, in particular, are the main actors. These violent groups, known locally as ‘militants’, are resisting the oil companies, local leaders, and the Federal government who they blame for their experiences of violence. The media and official discourses characterise these violent groups as criminals and problematic and blame them for violence. So far, there has been little systematic effort to give these youths a voice in discussions about violence in the Niger Delta.

She uses a political ecology approach which combines Bourdieu’s thinking tools (habitus, field and capital) with Connell’s concept of hegemonic masculinity, to understand petro-violence from the perspective of youths, and male youths in particular. This means an analysis that prioritises how young people perceive, explain and justify their relationship with violence. The findings in this thesis emerge from 5 events of focus groups and in-depth interviews with 84 youths mostly from two ethnic groups (Ijaw and Ogoni) and who have experienced oil-related violence in both direct and indirect forms. It also includes in-depth interviews with 42 institutional representatives who have relevant knowledge about youth violence in the Niger Delta.

In conclusion, the findings highlight the role of the political ecology of oil as well as institutional and social factors in shaping young people’s experiences of violence.

Close

Close