Current students at The Bartlett School of Architecture interview recent alumni from a variety of different disciplines and backgrounds.

In a new initiative from The Bartlett School of Architecture Student Society, students interview alumni from the school, connecting the experiences of past and present students. Released throughout the year, each interview explores the multitude of pathways taken by alumni to reach their destinations, exploring challenges and moments of disappointment alongside successes and accomplishments.

Interviews

- Arthur Kay

- Asif Khan

- Beatrice Galillee

- Chris Hildrey

- Farshid Moussavi

- George Clarke

- Jonathan Hagos

- Kulveer Ranger

- Luke Chandresinghe

- Sherin Aminossehe

- Usman Haque

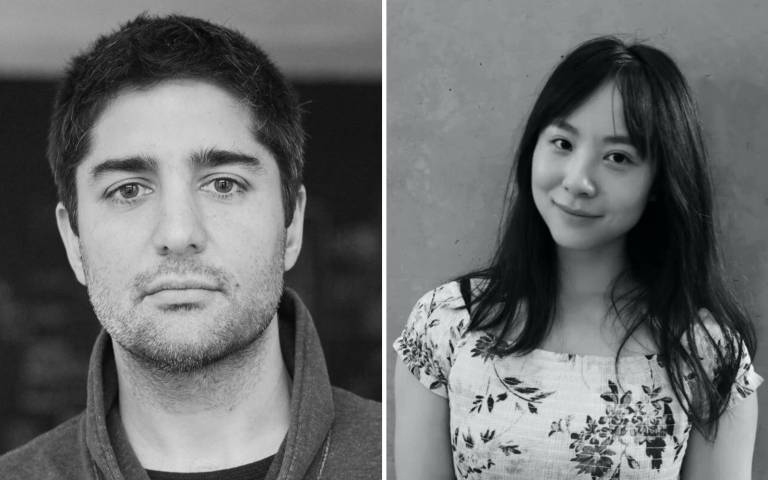

Arthur Kay

Interviewed by Winnie Lau

Arthur graduated from The Bartlett in 2013. During his studies he created bio-bean, a clean technology company that recycles waste coffee grounds into advanced biofuels. He also holds positions on a number of boards associated with social enterprise and green entrepreneurship, and is a Fellow of RE, the RSA and IoD. In 2013, Shell named him ‘the UK’s most innovative entrepreneur,’ and he was appointed as a ‘London Leader’ by Mayor Boris Johnson. In 2014 he became one of NESTA’s ‘New Radicals’, and was named in ’25 under 25 most influential Londoners’ by the Evening Standard and in '30 under 30' by Forbes Magazine. He was named the youngest ever Guardian Sustainable Business Leader of the Year.

Winnie: Could you start with your startups — a lot of them are not strictly architectural, how did these ideas came about?

Arthur: Yes - they are not architecture related per se in the traditional sense of it, but they are involved in urban design. I think The Bartlett and my architecture education generally really helped in being able to think laterally about different ideas and also to zoom in and zoom out to different concepts. So it's trying to think of things much more broadly rather than thinking of things just in a very specific narrow lane. I’ve tried to come up with projects that come from the city perspective — how does urban design in the city work? - looking at the key moving parts, whether it be cultural politics or social justice or inequality.

Winnie: And bio-bean, you founded when you were still studying?

Arthur: Exactly, so while studying architecture, I set up a think tank called Students For Happiness. It was looking at students' wellbeing, mental health and physical wellbeing, and trying to bring some amazing lecturers and speakers and thinkers together, ranging from Anthony Selden to Lord Richard Layard to AC Grayling. When I was at UCL, there was a high level of mental illness and mental health challenges, and so it was really trying to tackle that issue. Then, at the same time I set up a company called bio-bean, which is a renewable energy and clean technology company — it takes waste coffee grounds from all across the UK and turns them into a range of advanced biofuels and biochemicals. I came up with the idea while I was at university on an architectural project and then spent a bit of my time in my final year developing some technologies and processes and then went on to sell the company.

In the intervening years, we've raised tens of millions of pounds; built a world’s first factory in the UK; we've got patents pending for a number of different technologies and each year we recycle thousands of tonnes, which is billions of cups' worth of waste coffee grounds each year, saving hundreds of thousands of tons of CO2 emissions. It has really gone from strength to strength and it's been amazing to do that.

Winnie: What is the most distinctive memory of being a student at The Bartlett?

Arthur: Well the most distinctive memory was a double edged sword I'd say. One of the reasons that I set up Students For Happiness was to make sure that the overarching student experience is good, because it often felt like the quality of work was at the cost of the wellbeing of the individual students. So I think it’s about making sure that you can still create that incredible work without jeopardising happiness and wellbeing.

I think it's partly an architecture problem but it's the same across elite institutions around the world. A balanced lifestyle and a balanced approach to work can achieve better results than just working the whole time. I think a lot of students at The Bartlett recognise, for example, the value of cinema; of nature; of exercising and so on. I can certainly say from my own experience that every single project which has been successful for me has come out of ideas that are not directly related to the field of architecture. They are adjacent to it, but have fed into it and that's where innovation comes.

Winnie: How do you juggle your roles and put on different hats throughout the week?

Arthur: I teach at UCL, Imperial and am the Entrepreneur in Residence and I am also a trustee of the Museum of the Home - so I have a number of different hats that I wear. I think the key thing is a quote from Abraham Lincoln, which is, “Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I'll spend five of them sharpening the axe.” And so it's about spending a lot of time on time management, data management and planning ahead — meaning that when you're actually doing it, you're able to do it as effectively and impactfully as possible.

Asif Khan

Interviewed by Nnenna Itanyi

Asif graduated from The Bartlett in 2005 with a first class undergraduate degree in architecture. In 2007, he founded his own international architecture office. His projects range from cultural buildings and landscapes, to pavilions and experimental structures. Current projects include the New Museum of London, the largest cultural project in Europe, the carbon-fibre Entry Portals at Dubai Expo 2020, and over 6km of Expo 2020 Public Realm design. Asif, who has taught at the Royal College of Art and Musashino Art University, is currently a Deputy Chairman on the board of the Design Museum in London. He received an MBE for services to architecture in 2017.

Nnenna: Looking at your work, a mixture of ideas and elements shines through. Is there a quality that ties it all together?

Asif: We might get a little jaded and lose touch with nature and lose sensitivity for observing things, living in the city particularly, but, at the end of the day, we’re organisms with so many different tools built into us to experience the world: through tactile, visual, auditory senses and balance and so on. If you organise them in the right way, you can create architecture which transcends daily life. We deserve a city that inspires us and sparks creativity in us. Buildings are not just machines to be lived in or just vessels for things to be put into. Sacred buildings were multidimensional. They touched you in different ways with light and the moments happening in them. We need to bring that back into daily life.

Nnenna: So, we need different layers to our architecture?

Asif: Yes! I recently had a masterclass with some Bartlett students and one of the things which came up was the pathway for students from good universities to good practices. ‘Good practices’ are normally judged based on financial stability or commercial success. High-flying students are picked up by these practices and all the magic they have is reformatted because they are put in this machine of production. Essentially, all the innovation they had at the beginning is not relevant to commercial practices. The work that comes out of The Bartlett is architecture that can change our daily lives. The important thing is to not let go of it.

Nnenna: You definitely didn’t get in that rut because you started your own practice.

Asif: When I was at The Bartlett, we all wanted to start our own practices. One summer, I worked for my tutor for some months and asked him if we could start a company together – I was interested at the time in craftmanship and making – and he agreed. During 4th year, I was also doing public lectures and met a potential client.

Nnenna: What advice would you give to Bartlett students?

Asif: Get your work out there. Architecture students really have to believe in their work and get it out beyond The Bartlett. Confining yourself to The Bartlett is preaching to the converted. There's no benefit in convincing a tutor it's a good project. If you can convince someone external, like your grandmother, or a potential client, then people are paying attention to you, and you start to build up a different critique for your work. It’s not about the fishpond, it's about the big sea.

Nnenna: Were there any setbacks you had as a student?

Asif: I did a foundation course very last minute at The Prince’s Foundation. It was the best year of my life because it was hands-on and full of design. So, coming to The Bartlett, I felt I was really ahead. Weirdly, the first year ended up being tough – I had a block at the end and failed, which felt terrible. I took a year out and worked at a local small practice. When I came back, I had a newfound intensity. I didn’t know what my weaknesses were until I failed. It was a really important moment for me. Everything I have done since then has had that failure as its launchpad. It was the most positive thing that happened to me.

Nnenna: Was it the failure or the rebirth that came after it?

Asif: The rebirth. The failing knocks you down and you have to rebuild and re-evaluate and chose what’s important. In real practice failure is a constant reality. You run a business and you lose projects, or projects won’t happen, or your project gets ripped apart in the paper. Embracing failure helps you temper and become more comfortable in yourself.

Beatrice Galilee

Interviewed by Daniel Langstaff

Beatrice earned an Architectural History MA from The Bartlett in 2008. During this time she was also Architecture Editor for Icon Magazine, one of Europe’s leading publications in architecture and design. She went on to make a notable impact as the first curator of contemporary architecture and design at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Beatrice is now the founder of The World Around, a New York-based conference and platform for cultural discourse. She is internationally recognised for her worldwide experience in curating, designing and conceiving original and dynamic city-wide biennales, museum exhibitions, installations, conferences, events and publications, bringing together the world’s most important institutions with cutting edge practitioners.

Daniel: How did you get into curation with an architectural background, as opposed to someone from a background like art history?

Beatrice: The difference, I suppose, between somebody who studied art history and has always had the intention of being a curator is, maybe, a much more distant relationship to exhibition making or art making. As an architecture student - someone who was always making things and understanding how things are made - I always had a very hands on relationship to understanding the processes and production values. When you're in architecture school and you learn about Peter Zumthor, you understand it's not just about how it looks but how it's made; the material choices, the ways that materials work together, the engineering of things. And so, when you when you bring that into the world of exhibition making and curating, you do have this extra booster pack of knowledge that makes you identify very specific things about exhibition making and art making. I think that’s one of my strengths as a curator - being someone who knows how to make things but also understanding the history, drawing the connections and seeing the bigger picture too.

Daniel: When you’re curating, what do you prioritise? Is it a narrative, a journey, an atmosphere, or something else that you keep at the front?

Beatrice: I think - and this definitely has to do with my training as an architect - about the experience of being in the space, first and foremost. What's the encounter with that object, not just the object itself, but how it’s lit what the spatial components? What the floor’s like; the furniture; if there’s benches; how does it all work together as a whole?

Daniel: I assume that when you put things down on paper and then you go to the space, things are drawn in one way and then there’s a realisation that it all has to be rejigged to make it feel ‘correct’?

Beatrice: Exactly - the lighting, and the sound, and sometimes things can even seem harder or softer in the space and you have to be able to calibrate that with all of your senses. It's not something that you can just intellectually decide on paper and write down, you really have to be able to sense it. I think all of those components, like the typography and title, and even the introductory text, really matter to me as a curator.

Daniel: Moving further into your career, how did you find your way out to New York, and the Met?

Beatrice: I applied for the job of architecture curator at the Met, the first ever architecture curator there, not really knowing what it would entail and not really knowing if I was really the right person for it. It turned out to be a really amazing match and a really great experience. On my first day at the Met it happened that Adrian Forty, who was my Professor for my Master’s, was in New York and so we had a cocktail together at the end of the day. It was amazing to have that continuity from someone who'd shepherded me through my Master’s, had been so patient while I was traveling around the world and was late with all my deadlines, and then was there and proud of me when I was starting out professionally.

Daniel: Finally, what advice would you give to current university students?

Beatrice: Do what you're good at. I think that often when you're a student there's things that other people are good at or that you feel like you should be good at because that's what you’re supposed to do. With me, my ‘thing’ is that I love writing and organising events about architecture so I thought ‘How do I do this as a job?’. I found how it made sense for me. I knew that I was okay at designing and that I could probably be an alright architect, but it wasn't really what I was good at; keep in mind that there’s probably something that you absolutely love doing and that's the thing you should listen to the most.

Daniel Langstaff

Daniel is an Architecture BSc student at The Bartlett. His interest lies in the emotional impacts of design and the presence of architecture in journalism and film, and he has explored this throughout his studies. He is part of the dance and skating societies and is an incoming committee member of The Bartlett School of Architecture Society.

Chris Hildrey

Interviewed by Sharil Tengku Abdul Kadir

Chris graduated from The Bartlett’s Architecture MArch programme in 2009 and the Postgraduate Advanced Architectural Research programme in 2012, and has since started his own design practice, Hildrey Studio. He is the founder of the widely publicised project ProxyAddress, which won the RIBA President’s Medal for Research as well as a nomination for Beazley Design of the Year in 2019.

Sharil: I’ll start off by asking: what is ProxyAddress?

Chris: ProxyAddress is a system to give people who are facing homelessness a consistent address which can use to access the services and support that they might need. What it looks to do is to overcome a catch 22 that people face when they’re homeless; which is that when you lose your home, you not only lose your shelter, but you also lose your address. And with that, effectively, you lose your identity.

Sharil: So applicants of ProxyAddress are matched with an address from one of the roughly 500,00 houses currently empty in England. But aren’t there various privacy related risks involved when property owners lease their addresses to a complete stranger?

Chris: Well it’s a very good question. Because the original idea was that. And as with most concepts, they get whittled down through reality. And they end up as something a little more precise. As you said, there’s around 500,000 empty homes in England, but we stick to the 250,000 ones that have been vacant for more than 6 months, which is long term vacant. Because also in terms of ownership, that was the real crux of the project: the question – what is an address? The address is by definition, the most public information we have in the built environment. This becomes another design question. We have things like, when projects are in construction, we can use those while they are not being used. Council owned properties as well. But also, personal donations; you could give someone a fiver on the street, or you could also, for free, allow us to give them your address.

Sharil: What would be your advice for students looking to work with vulnerable groups of people as part of their own projects, without coming across as patronising?

Chris: I think design often talks about the importance of empathy - but more important than empathy is a degree of sympathy. It's being able to put yourself in someone else’s shoes when you haven’t lived in that position yourself. And the most important thing in those situations is to listen. I think sometimes you might get a bit of resistance because I think there is a bit of a stigma around people from a design background. I think that they imagine a designer to be somebody who has a vision of the world and expects to declare that vision and everybody else to shift and adapt to meet that vision. The way I overcame that was by making sure to see this as a design problem. The first part of the design project is creating the brief by speaking to people and listening to what their issues are. So don’t be afraid to speak to people.

Sharil: If you had the opportunity to speak to your student self, what three messages of advice would you give?

Chris: I think looking back on my student days was almost as educational as my experience during my student days. Because information comes at you at such as pace, it’s quite hard to take that all in, you still digest it a decade afterwards. So I think one of the key pieces of advice I would have given myself is to listen to my instincts more. Another is don’t worry too much about being original. I certainly as a student got what’s called paralysis by analysis. If you start doing something and then you think, well, this first footstep isn’t original enough. Actually, over time you come to realise that almost nothing is original. I think it comes down to a fact that the most original thing that anybody will experience is themselves. If you can manage to feed your own creativity from different sources whether it be music or film, or books you will end up being a black box where you’ve got an input of all the things that you seek out and you use that as the basis to output something. That will always be original.

Sharil Tengku Abdul Kadir

Tengku Sharil is a recent graduate of The Bartlett School of Architecture’s Architecture BSc programme, through which he conducted research on rethinking sustainable and collective methods of design. His thesis project, “One Tree Manual”, was awarded the RIBA 2020 Bronze medal, AJ Student’s Sustainability Prize, and the Bartlett Medal. He is currently working as a Part 1 Architectural Assistant at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners in London.

Farshid Moussavi

Interviewed by Sharil Tengku Abdul Kadir

Farshid graduated from The Bartlett in 1989. She is known for buildings such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Cleveland and the award-winning Yokohama International Ferry Terminal. Alongside leading the award-winning architectural practice, Farshid Moussavi Architecture (FMA), she has been Professor in Practice at Harvard University Graduate School of Design since 2005. In 2018, Farshid was awarded an OBE for her services to architecture. She lectures regularly at art institutions and schools of architecture worldwide, and is a published author.

Sharil: Why did you choose to study architecture?

Farshid: I’m afraid I don’t have anything too unusual to tell you, other than the fact that I was attracted to its multifaceted nature. It’s creative, but also practical. You could say there’s a kind of a scientific aspect to it, given the fact that it works with a lot of technical aspects. I think that the multi-parametric nature of it attracted me. But really, it was a kind of intuition. I could have done other things. I did physics, chemistry and mathematics at A-levels, a combination that can take you down many different routes. I wasn’t as decided as you might expect. Thankfully, once I started studying architecture, I realised I really enjoyed it, but there were friends of mine who left to join other degrees. I don’t place too much value on that initial moment of decision, but more on the fact that I realised that I had made the right decision later.

Sharil: Do you think that innovation in architecture is stifled by the need to incorporate an ever-increasing number of considerations – like sustainability – that function as a moral straitjacket for architects to adhere to?

Farshid: I believe that contemporary practice is very different to what practice was 20 years ago. Architects must work with many more regulations, codes and conventions, because of the greater demands on buildings. But, as an extension of that, architects now work with a lot of other experts that advise or consult. I think that they bring an enormous amount of knowledge to the architect about matters that the architect is not as skilled in. As a result, the architect needs to operate differently. The architectural process can no longer be about coming up with a fantastic idea at the beginning and, in a very linear fashion, turning it into the final built form. The process is far more unexpected, it has to be approached as a space for experimentation and an opportunity for thinking differently about buildings on different scales. Over the duration of the design process you become more informed; you learn new things.

So, I think that contemporary practice results in a different kind of building. I refer to it as an assemblage of different components, different parts that together are more complex, not geometrically, but as experiences or encounters that open up for people. Architects are often expected to come up with a grand narrative to simplify the building, like ‘my building is about sustainability’, but buildings should be about many things at once because they simultaneously relate to so many arenas. Contemporary practice is rich and full of possibilities for experimentation, and for architects to take buildings into new directions.

Sharil: You’ve approached design from the position of an outsider, could you share how you have included this within your design process?

Farshid: The idea of the outsider comes in at the beginning of every project by assuming we don’t know anything about that subject. It’s not easy, but you try to put away your preconceptions and begin every project as if it’s a fresh start. By thinking uniquely and specifically about each element, rather than simply applying what you already know, you are acting as an outsider. So, being an outsider is an elected position. Yes, I wasn’t born in the UK, and I don’t necessarily look like everybody else who lives in the UK, but my interest in being an outsider or foreign is not really about that. It’s about a state of mind. It’s a position that anybody could adopt. It has to do with creativity, experimentation and being open to change.

Sharil: If you had the opportunity to speak to your student self, what message or advice would you give?

Farshid: Well, one of them I have already mentioned is that you need to be open to change. Don’t think so much about planning your career, but rather focus on enjoying your work and responding to the opportunities that you have right now. Follow your instincts in respect to the world, and the social and political context around you. Don’t assume that you know what architecture is, and don’t assume that other people’s responses to the world around us have to be the same as yours. Being independent and enjoying the work you do is really important because it comes out through the work eventually.

George Clarke

Interviewed by Daniel Langstaff

George is an architect, television presenter and campaigner, best known for his work on the Channel 4 programmes The Home Show, The Restoration Man and Amazing Spaces. He is an ambassador for multiple charities including Shelter and The Maggie’s Centre, a trustee of the Foundation of Light, and patron of the Civic Trust Awards and Knights Youth Centre. George founded the ground-breaking Home Education charity MOBIE and is the cultural director of the new ecological home development company X HOME.

Daniel: I noticed that you mentioned that your grandfathers, who were builders, were a large inspiration to you. What was it about building sites that stuck with you?

George: Back when my friends were seven, eight, nine years old they were playing with the little Tonka cars and trucks and lorries, and I was in the real things in my granddad's cabin. I just love being around the building process, people actually making something; it was as simple as that, really.

Daniel: What would you say is like the most impactful project that you’ve done in your career as an architect?

George: I think one of the really exciting turning points, just before I went to UCL and after my year out, was when I went to work in Hong Kong for Farrell’s. I was there for seven or eight months working on several railway stations linking Hong Kong and China and looking back that blows my mind because I was only 22 or 23. I had the responsibility of working on some big urban design projects that would transform parts of Hong Kong and now they’re built, they’re done, they're all completed! You can go back and see these mega projects. When you build a railway station in Hong Kong, you have to consider the railway station itself, then you have all the retail that’s above it and the residential that’s above that; you’re designing mini cities in the city. Hong Kong was the most impactful time in my career because it just expanded my mind to global architecture, rather than just national architecture.

Daniel: Across your television productions, and books, and ambassadorship for charities like Maggie's and Shelter, the concept of ‘home’ seems to be prevalent throughout. Why is this concept important in your work?

George: When I set up my own practice back in 2000 after finishing at The Bartlett the year before, all we did was houses – that was it, that was all our work. It was mainly residential work in London, so we became a practice known for residential projects. Then, when I started doing TV, the main property brand for Channel 4 was, and still is, all about ‘home’. Practically every single architecture, property or design show that Channel 4 does, whether it’s me, Kevin McCloud, Kirstie Allsopp, Sarah Beeny, Phil Spencer, whoever it might be, it’s all got a connection with ‘home’. That’s no coincidence because, for me, home is probably the most powerful piece of architecture in your life. You might go and visit lovely buildings, you might go to beautiful museums or galleries, amazing commercial skyscrapers or hotels, and yes, you might be inspired by them and you might fall in love with them and they might have a big influence, but as a piece of architectural ‘stuff’ – space and bricks and mortar – your home is, without a doubt, the most important place in your life.

Daniel: What movements would you like to see emerging architects stand behind?

George: If I'm honest with you, I think the biggest movement – and I’m sorry to jump on the bandwagon – is net zero. The climate crisis is the biggest challenge we face as architects today. I’d love to sit here and talk about styles or principles of architecture and how we should design wonderful buildings in a certain way, but I think we have to address the time of crisis we live in. We need to be green and that’s an amazing design challenge – I think it’s a wonderful opportunity, I don’t think it’s a constraint.

Daniel: What is your most distinctive memory of being a student?

George: Well, I’ll be honest, my time at The Bartlett was really hard work. I was in Unit 21 with CJ Lim and Christine Hawley and it was brilliant. My god, it was creatively probably the best two years of my life! We were pushed to do beautiful drawings and schemes. Everybody that came out of that unit did incredible work.

Jonathan Hagos

Interviewed by Kaia Wells

Jonathan is a director of Freehaus, a RIBA chartered practice dedicated to putting people at the core of their outputs, designing accessible interventions within historic contexts across the country and abroad. Jonathan sits on the Quality Review Panel for the London Legacy Development Corporation and the Hackney Regeneration Advisory Group. He holds a BSc and postgraduate diploma in architecture from The Bartlett. Jonathan also led the production design for the award-winning feature film Simshar, highlighting the plight of refugees across the Mediterranean.

Kaia: What is your most distinctive memory of being a student at The Bartlett?

Jonathan: Feeling woefully unprepared for everything! The shell shock of coming into an environment where I didn't quite know what was going on and not quite feeling that I was running at the right pace. That feeling lasted probably until I completed my BSc.

Kaia: Were there coping mechanisms that you found, in hindsight?

Jonathan: The mistake I made was being solely immersed in the world of academia. By my postgraduate, one of the key coping tools I employed was taking a part-time job at an art college in Cambridge – being removed from the academic environment of university was incredibly freeing. As a result, my postgrad was an incredibly enjoyable experience for all the reasons that my undergrad wasn’t. One of the reasons people don’t take a break is that they are scared to stop in case they won’t be able to start again. World-renowned design practices share their stories of all-nighters like a badge of honour, giving students the impression that they need to do the same in order to succeed. But it’s very short-term thinking, because it doesn’t work and it can’t be sustained.

Kaia: In terms of your practice, it’s really wonderful seeing so much community engagement. Could you tell us more about that?

Jonathan: When we set up our practice, we consciously wove in engagement opportunities within our design process in order to understand the collective voice of a given project and the diversity of that voice. A lot of our initial projects had a small budget or needed to be delivered quickly, so we created opportunities for local people to help build and organised fun days for community groups to help define aspects of our brief. So from very early on, co-authorship and co-design opportunities were embedded into our design methodology. We examine the clarity and accessibility of our communication, the words we employ, the way we draw and the images we use. We try to demystify the process of architecture. The more voices you have and the more experiences you can draw from the richer the output will be.

Kaia: I often see tokenistic community engagement. For example, ‘a community consultation’, which is really just a one-way conversation. Have you experienced this?

Jonathan: The local authorities, developers and charities that we work with are so live to the importance of engagement that it is a key part of the design process. As our client at the Africa Centre said, ‘engagement is a way to build a community around a project’. Community groups expect to be engaged with, and rightly so! If there’s something that’s going to affect the quality of their lives, the quality of the air they’re breathing – it’s really important that they have an understanding of how construction is going to impact them. Not only do you have a responsibility to do community engagement, but it needs to be as considered as the architectural output.

Kaia: What movement would you like to see emerging architects stand behind?

Jonathan: There are so many obstacles to academia, the education system should be geared towards making a profession that is more representative. There’s not necessarily one movement, but we should champion anything that makes the profession more equitable. Anything that challenges the structure and route through to the profession is refreshing. Look at what the London School of Architecture are doing (creating different pathways into academia); what the Part W collective are doing (championing women’s rights in construction); or what Sound Advice are doing (improving racial diversity in the industry). I would say – don’t be apolitical, as hard as that might be. It is really important to take a position, because the way in which we work is fundamentally politicised. Fighting for your cause, and fighting for the causes of others, is really important.

Kaia Wells is in her final year of Engineering and Architectural Design programme at The Bartlett. She is currently designing the infrastructure for the canal boater’s community in London as well as writing a dissertation on inclusive design within it. After completing her degree, Kaia will be taking a few years out of university in industry, before going back to study and completing her architectural qualifications. In the future she is hoping to put her learnings of inclusive community design into practise.

Kulveer Ranger

Interviewed by Siobhan Obi

Kulveer Ranger graduated from The Bartlett in 1997 and entered the field of management consulting. In 2008 he was selected by the Mayor of London's administration to become the Director for Transport Policy. He was later appointed as the Director for Environment and Digital London; one of his significant achievements was a record fall in bike thefts resulting from his work. He has also worked on new electric car charging points in London to encourage a higher take up of electric vehicles. He is presently a special adviser to UK government on digital strategy.

Siobhan: What is your most distinctive memory of being a student?

Kulveer: It was the amazing diversity of the background of people. I was an 18 year old coming from an all-boys school but then landing in The Bartlett, I found this almost overwhelming sense of different people, all with different backgrounds. It was people who'd been working in industry, for years, not necessarily in architecture. I think when I started out in first year, out of about 40 people, there was only a handful of us who had come directly from school. You really do suddenly feel like you're in a world of grownups because The Bartlett, even then, attracted lots of people from all over the world.

Siobhan: If you had the opportunity to speak to your student self, which three pieces of advice would you give?

Kulveer: To be honest, I wouldn't want to be giving too much advice to myself, because you're on this journey and you don't want to spoil it by pointing out what you should be doing. You learn through going forward, testing things and just experimenting. I’d like to think that I would do similar things again, I really enjoyed my time at The Bartlett. It was rich, it was fulfilling and it was very challenging, as it should be. I wasn't one to be overly worried about things, I think you need to always stay calm in the environment and keep taking things on board. One thing I would say is probably just to read even more than I probably did.

Siobhan: What is the most radical architectural idea that you’ve had or heard to date?

Kulveer: I was fortunate to have the responsibility for London transport policy. I was involved in delivering the Oyster card. Technology has transformed how we move within a city and the card enabled seamless interoperability between modes of transport. It changed the dynamic of movement around the city. Furthermore when I went into City Hall, one of the challenges I saw was that we were almost abusing our city in terms of what we were doing around design of roads and the road network. Bendy buses were coming into London and to accommodate them, we'd been eating away road base or putting in guardrail. My first year field trip was to Barcelona, and you saw the Ramblas and what the Catalans had done there in terms of pedestrians at the centre of roads. Getting that kind of architectural thinking into London, from a transport perspective, was really something different.

Siobhan: What is the importance of an interdisciplinary education when dealing with matters of the built environment?

Kulveer: It's essential as an architect or as anyone who can have an influence on the world around us. As individuals, we have to be more open to other influences and other factors, you can't have a linear view. In terms of disciplines, an architect has to be the ultimate diplomat, project manager, creative and politician to keep everybody happy. You've got so many different interests that you are trying to satisfy, whilst also trying to maintain the purity of a design. The more that gets eroded, the overall value of what you're trying to do might be getting eroded as well, so you have to manage all those different elements to keep the value of the idea.

Siobhan: What has it been like having to get the buy in of people and the government with regards to climate change?

Kulveer: I would say it's not about environment projects, it’s about any project. You have a cohort of people, a broad stakeholder group that will all have different views and different vested interests. When we talk about environmental initiatives, the pendulum has swung completely from where it was right on the niche end of the spectrum of policies, to where it's become extremely mainstream and fully understood. Environmental policy got the conversation moving, encouraging manufacturers to bring more to the UK. Sometimes you know the market needs that push from politicians. It has been a lot of effort to get that change to happen so that's very pleasing.

Siobhan Obi

Siobhan is in her final year of Architectural & Interdisciplinary Studies BSc. She is Co-founder and Treasurer for The Bartlett School of Architecture Society. Through her time at The Bartlett, Siobhan has developed a special interest in sustainable cities and climate energy solutions. She has gained experience in energy infrastructure with the Africa Finance Corporation and hopes to continue bringing positive change to communities with diverse architectural knowledge.

Luke Chandresinghe

Interviewed by Heba Mohsen

Luke Chandresinghe studied at The Bartlett for his undergraduate and postgraduate degrees, graduating with a first class degree at undergraduate level and a distinction at masters. His undergraduate project was awarded The Bartlett Medal and was nominated for the RIBA Bronze President’s Medal. Luke’s postgraduate project was also nominated for the RIBA Silver President’s Medal and awarded both the Bannister Fletcher Medal and the Sergeant Award for Drawing. Between his undergraduate and postgraduate degrees Luke spent time in Japan on the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese scholarship. He has since worked at a number of prestigious practices, and in 2007 he set up the Tokyo Architecture Workshop. Luke is the Design Director of his own practice, Undercover Architecture.

Heba: Something I found really interesting about Undercover is how a lot of your projects are designed by the practice in totality. Why does this multidisciplinary and holistic approach appeal to you?

Luke: My formal education, was at bigger practices, working on a scale where you don’t get into the details or what the building feels like. The plan with opening Undercover was always to try and do smaller scale work. Architects can see interior design and architecture as very separate but we wanted to try and encompass all aspects of a home. A home is not just the architecture. Designing the building is, of course, difficult but giving a soul to the place can be even harder. My wife Estelle works very closely with the Undercover studio, she’s from a fashion and textiles background and my view on texture, textiles, lighting and materiality exploded when I met her. She’s the one who’s not the architect, but picks up on all of the things that make our projects much more whole and give them some vibrancy and spirit. I think that’s what makes us different.

Heba: What processes do you go through to choose your materials, and do you have any advice to current students exploring materiality?

Luke: My undergrad and postgrad tutors weren’t afraid of colour and texture, this was very liberating because it meant you could make mistakes and be bold. I don’t have instructions about what materials to use but definitely don’t just look at social media, following trends is very dangerous. At Undercover we try to ask what is the light in this place? What are the surrounding materials? What was on the walls a hundred years ago? As a practice we find a lot of inspiration from history. If you go back and look at the materiality you’re concerned with in its most raw usage and then incorporate modern techniques to use those materials, you come up with a really strong way of designing.

Heba: Do you have a favourite project that you’ve worked on at Undercover?

Luke: They’re all different, and they’ve all had challenges but they’ve all had moments of greatness. I think this next round of projects will be the ones that give us the platform for our seminal projects at Undercover. However the Lennox Gardens apartments sticks out to me, in terms of refinement it is really up there. The staircase took a lot of work to make it successful and the end result was really beautiful.

Heba: Reflecting on your time at The Bartlett, what was the thing you struggled with most?

Luke: I think at The Bartlett you can struggle with the awareness that you’re at one of the best schools in the world. When I was there, and I’m sure it’s the same today, there was a lot of pressure to perform in a very competitive environment. At first I didn’t think I had any tools to be working as an architect in an office. Later you realise you have so many transferrable skills, but you can’t really be taught creativity. Without the education I had at The Bartlett and the opportunity to explore design resources that had nothing to do with architecture, I don’t think Undercover would be as fruity or inventive.

Heba: If you had an opportunity to give your student self some advice, what would it be?

Luke: Firstly, understand the business side of architecture. A lot of people don’t realise it’s part of being an architect and it creates students that are just terrible at selling their ideas. It’s a skill as important as doing the work, if not more important. If you don’t sell the idea to the client the project dies. I would also recommend working on the other side of architecture, the contracting side. During my part two I worked for seven months as an architect on site - in my hardhat and boots all day. I think a lot of architects are really happy standing behind their screen or their drawing board, drawing away. Unfortunately, that’s not the real world. I’ve learned more, and still do, from working with contractors and artisans and fabricators, than from being inside an office.

Heba Mohsen

Heba Mohsen graduated from The Bartlett’s Architecture BSc programme last year. Her third year final project ‘Florida Peak’ was awarded The Bartlett Medal and a commendation for the RIBA President's Bronze Medal. Heba is interested in narrative architecture and diversifying ideas of who is an architect and what is architecture. She is currently working as a Part I Architectural Assistant.

Sherin Aminossehe

Interviewed by Hao Zhang

Sherin graduated from Architecture BSc in 1998, Development Planning MSc in 2000 and Architecture MA in 2003. She began her career at Farrell’s before moving to HOK where she worked on large infrastructure regeneration projects in Jeddah, Bahrain and St Petersburg. She is currently Director of Infrastructure at the Ministry of Defence. Previously, she was Head of the Commercial Office business at Lendlease and led the company’s social impact strategy.

Hao: The first question is about your time as a student - what is your most distinctive memory of the Bartlett?

Sherin: I can't boil it down to one, but probably the strongest memories are of Wates House before it was beautifully redesigned. The Wates house that we learned in had lots of holes in its walls and legions of students had painted it over many times. One of the first things you had to do during your first year was to paint your studio and make it your place. I think it probably still had asbestos in the walls when I was a student and people used to smoke in the building!

I'd be interested to know what tutorials are like now, back then tutorials frequently started about four or five hours late. I wonder if it's a bit more disciplined these days. I particularly remember crits, I think that's one of the ways I built my resilience. There's nothing like standing there with drawings that you've worked your heart out on and then somebody says "That's rubbish, what were you thinking when you were doing this?" So that's probably one of my strongest memories.

Hao: What would you say was your greatest setback during your architectural education, and how did you overcome it?

Sherin: At the end of my first year the Head of the First Year said to me that I would never become an architect. She tried to fail me but I was lucky in that I was pretty studious and my History of Architecture marks and my Materials marks were quite high so I went through. I still had to do some extra work in the summer on my design portfolio, and so it was really interesting because having gone through school I had never really failed at anything.

It was an interesting time and I think one of the things I learned from it is: just because somebody says something about what you, doesn’t mean that you have to accept it. I think it made me much more determined to get to where I wanted to get to. In a way I suppose, she was right because I'm not practicing, I am still a qualified architect and a member of RIBA, but I don't actually work as an architect anymore. So maybe she had something.

Hao: Young architects and graduates, particularly international students, struggle with finding employment, what advice would you give them?

Sherin: We’re in difficult times at the moment, both in terms of the economy, but also the broader design picture. Not everybody wants to build at the moment, it's uncertain where investors are coming from. So one of the things I would say is really work on your network. Your first contact with employers shouldn't be 'here's my CV', your first contact should be trying to get to know the company and trying to let them get to know you. I was really lucky that I had much wider interests and I was quite interested in politics. As a result, when I was in my early 20s, I wrote quite a lot of articles for the Architect's Journal. So my name was known and as a result of something I organised in the House of Commons, I was invited to the RIBA President’s dinner. That was my job post diploma because of that broader contact, so networks are really key.

Hao: Finally, what radical movement would you like to see students rally behind?

Sherin: Something that really irritates me at the moment, is all this conversation about a new normal. I don't think that should be acceptable, I think we should be striving to go back to what things were like and not accept that things have got to dramatically change. I think design is a really key part of it. I would love to see some thinking from students in terms of how we can design certain things better and use design as a tool for good in terms of some of the social issues.

Hao Zhang

Hao Zhang is an Urban Design MArch student at The Bartlett School of Architecture, working as a postgraduate teaching assistant and a faculty student rep. Her current research focuses on pervasive urbanism in terms of radical reimagination of urban commons as hybrid infrastructures. Her current project uses environmental and social data to assist design for alleviating gentrification in King’s Cross. Before joining The Bartlett, Hao worked as a Class 1 Registered Architect in China, with a Bachelor's degree in Architecture (5-year programme).

Usman Haque

Interviewed by Hao Zhang

Usman completed his undergraduate (1993) and postgraduate (1996) studies at The Bartlett; he was a part of units 4 and 14. He is now a founding partner of Umbrellium, a practice which designs and builds urban technologies to support citizen empowerment and high-impact engagement in cities. Earlier, he launched the Internet of Things data infrastructure and community platform Pachube.com, which was acquired by LogMeIn in 2011. His skills include the design and engineering of both physical spaces and the software and systems that bring them to life.

Hao: For the last few months you have been working for as creative director on a new urban rewilding project Wilding London. It is a complex project including community initiatives, landscape infrastructure, built environment and digital infrastructure. What are the main challenges in the participatory of urban wilding?

Usman: Rewilding in general is already a complex topic. Rewilding is about the introduction, or in some cases, the reintroduction of natural systems, animals, vegetation and so on and so forth, that might have previously existed, or that might benefit a particular environment. But what makes it even more complex is that different communities and people with different cultural backgrounds actually have a completely different understanding of what it means to have these kind of systems in cities. The perspective on rolling out these kind of green spaces, green technologies, green buildings needs to account for the fact that different people, different stakeholders, different neighbourhoods will have a different approach to this kind of thing, particularly when you are trying to do this in such a way that actually challenges our way of life. What, for me, makes it most exciting and interesting is to try and figure out how to manage that complexity.

Hao: How do you build participation in the context of 'super wicked' problems in the urban environment?

Usman: One key element is developing trust among the different participants. People in any neighbourhood, in any city of the world, probably have completely different opinions about all sorts of things to do with the urban environment, before they even start the project. One has to figure out what those trust exercises are based on what the project actually is.

Hao: What is your most distinctive memory of being a student?

Usman: The most distinctive memory is not necessarily my best memory, but one of my most distinctive memories was I almost failed at one point in my undergraduate. It was very hard for me actually doing architecture. There were some students I remember in my year who seem to be able to just do amazing drawings, amazing projects and they leave early and they always did fantastically well and it seems so natural to them. Particularly in my second year, and even part of my third year, I was really finding it hard. I actually did not understand what I was doing. Part of the reason I think that I was struggling so much is because I was trying to make sense of what everyone else was doing. There was a crit I had and someone told me about Malevich’s White on White painting, which seemed to have nothing to do with the project I was doing. But I became so intrigued by this whole body of work and this idea of White on White. It unlocked for me a kind of obsession and in being able to pursue that very personal thing. I think that's what helped me overcome the fear. By going through the hard stuff you learn a huge amount. I think you just have to find your own passion, because it's really the only thing that you can actually hold on to.

Hao: What advice would you give to current architecture students or students in general?

Usman: I think (for) architecture students I would say that in terms of developing your practice, one of the most useful things I've always found was to try to build things, not just to remain at the design stage but actually to try and build and prototype something. When I say build, I mean actually to try to do something in the physical world and not just at the design level. So even if you don't have any physical material you can still almost like act it out as a human being. You get something, I believe, from having the thing in your hand and trying to move it.

Close

Close