Alumna Rebecca Spaven reflects on the life of Gertrude Leverkus – the first woman to officially enrol at The Bartlett School of Architecture, in 1915, leading the way for generations of other women.

Portrait of Gertrude Leverkus as a young woman. Credit: The Leverkus family

Gertrude Leverkus’ 1922 RIBA Nomination form. Credit: RIBA Archives

On Gertrude Leverkus’ 1922 RIBA Nomination form, the standard text that reads, ‘We the undersigned do, from our personal knowledge of him, propose and recommend him for election’, has been modified: a neat cross through ‘him’, replaced with a handwritten ‘her’.

Leverkus was one of the first three women to go into architectural practice as RIBA members, moving in a sphere still almost exclusively reserved for men. She would have lived her life constantly aware of her womanhood, existing in opposition to the expected appearance of ‘Architect’. When she mentions her ‘otherness’, however, it is almost always in relation to men’s bafflement at her presence, rather than feelings of anxiety or alienation.

In 1928, speaking at a conference of women voters about architecture as a career, she noted that, rather than outright discrimination, she was often greeted with bafflement by male colleagues. She described how, on one occasion, “a man actually took off his coat for me to kneel on when inspecting an excavation. Later, however, he got so used to me as a fellow-worker that he forgot himself completely and invited me to a public-house”.

The first woman

Gertrude Leverkus was the first woman to officially enrol at The Bartlett School of Architecture, in 1915. Two sisters, Ethel and Bessie Charles, had taken classes in the 1890s, but did not have the option to graduate, so this honour was bestowed upon Gertrude.

She applied to UCL as it was the only option for architectural study in London open to her. The Architectural Association did not yet admit women, so she embarked upon the three-year B.A in Architecture, studying under F.M. Simpson; later taking evening classes with Albert Richardson, then the Town Planning certificate with Stanley Adshead.

In her memoirs, she confesses to being “very alone” although “never depressed”. There were two women in the year above her, but neither of them completed the course, and even the men in her class, many soldiers and overseas students, came and went without having much impact on her life.

Leverkus instead buried herself in her work and extracurricular pursuits, joining the College Dramatic Society, putting on plays and making gothic scenery out of brown paper. She sought company in women students outside The Bartlett and speaks fondly of several close friends she made, in particular ‘Hilly’, who was Flinders Petrie’s secretary in the Egyptology Department, and who “opened her eyes to a very different and far more Bohemian way of life”.

Leverkus’ feminism was one of practical support, solidarity and organising. She wanted more and better-trained women architects, and a network of friends and colleagues to help with her mission. In 1932, she helped establish the RIBA Women’s Committee. Originally intended as a women’s social club, Leverkus steered it towards a hands-on approach, promoting the interests of women architects, assisting graduates in job-hunting and recording cases of discrimination.

This spirit of practical caregiving extended into her professional career. In 1930, she was hired as the in-house architect at Women’s Pioneer Housing, a co-operative society that provided low-cost rented accommodation to single women. She single-handedly designed 40 property conversions into self-contained apartments.

She was a passionate advocate for what we would today call ‘widening participation’ and was often asked to advocate for women’s involvement in architecture. In 1939, she was invited by the Suffragette Fellowship to the 21st Anniversary Dinner of women’s enfranchisement to represent her career.

Challenging discrimination

Leverkus begins one (undated) essay: “Happy is the girl who can find such a fascinating outlet for her energies as the profession of architecture, but varied must be her talents and many-sided her interests.” Architecture, she believed, “is one of the best professions in the world for those whose minds work constructively and tidily,” and perfectly suited to a creative but down to earth young woman. She elevated the status of housing design, rejecting the notion that the ‘domestic’ or ‘homely’ were lowly forms suited merely to women, but instead a chance to contribute positively to the nationwide housing shortage.

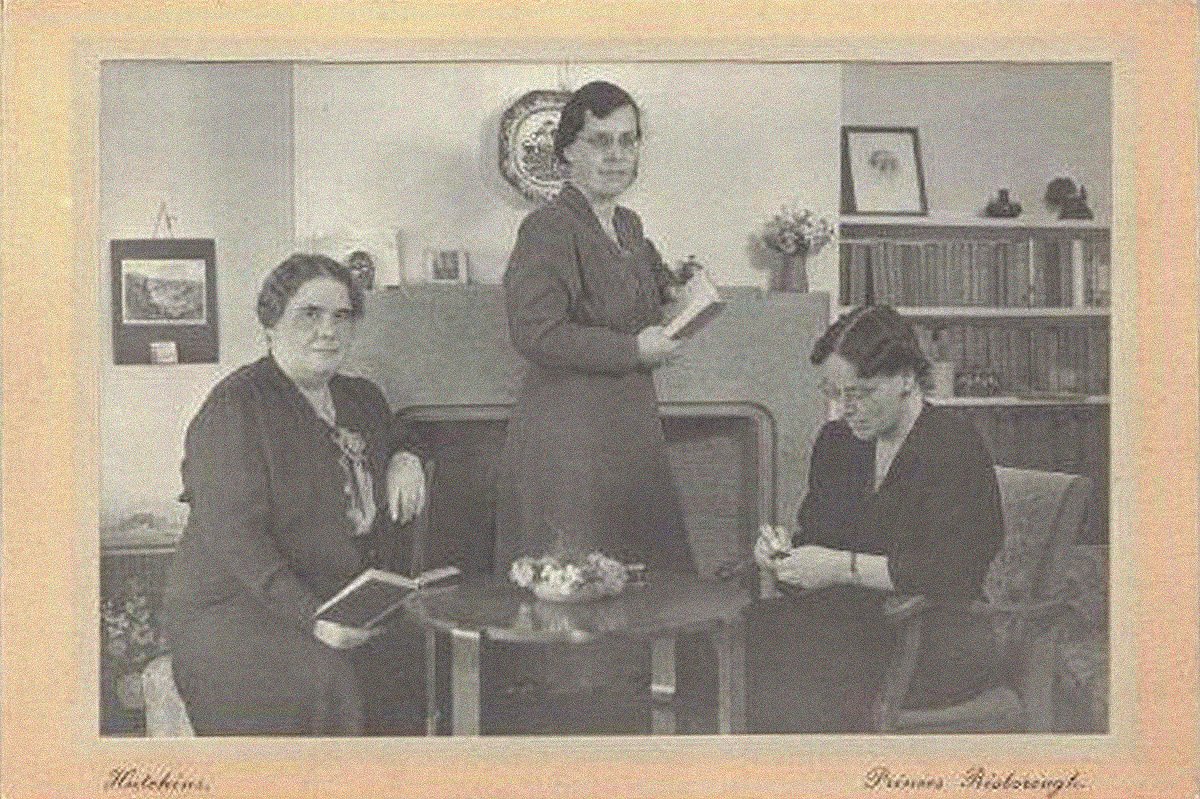

Gertrude Leverkus (centre) and her two sisters, Ethel and Bessie Charles. Credit: The Leverkus family

In 1943, she was appointed Housing Architect in the Borough Architecture and Town Planning Office of West Ham when it was being used as a test subject for Abercrombie’s post-war rebuilding project, the Greater London Plan.

In 1948, she joined the offices of Norman and Dawbarn, who were architects for the Crawley and Harlow New Towns, and Leverkus became jointly responsible for the conversion of unoccupied farmland into new neighbourhoods, making detailed drawings of new house and flat types, designed to house families coming from overcrowded cities.

When I was tasked with researching Leverkus’ life for a publication celebrating the School of Architecture’s 175th anniversary, two resources helped round out my picture of her. The first was a typeset memoir, written in Leverkus’ voice, entitled ‘Auntie Gertrude’s Life’, donated to the Women’s Library by her friend Kathleen Halpin in 1997.

The second was a series of conversations with Peter Leverkus, Gertrude’s great-nephew, whom I found during a search for her sister Dorothy, a GP. Peter had submitted a comment on a site about Leverkus House, a care home in Chinnor, and I contacted him on LinkedIn, discovering that he had a wealth of documents and photographs of his great-aunt, along with some very fond memories.

Through these personal traces I feel I’ve got to know Leverkus, the warm tone of her writing, the clear pleasure she took from her work and her straightforward approach to overcoming and challenging prejudice and discrimination both for herself and for her fellow women architects.

She is an example of how richly rewarding it can be to unearth histories of professional women at this time. The details of her life are hard to come by, and her career was by no means the most remarkable among her peers, but she represents a pioneering group of women who, by choosing careers hostile to them, at institutions where they were odd ones out, began to break the monopoly that men had on professions like architecture.

Rebecca Spaven studied Architectural History MA at The Bartlett School of Architecture.

Close

Close