Toyota and the Terracotta Army: mass production and mass media

11 January 2013

Last year ended with a substantial amount of media and blog coverage triggered by our publication in the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory.

What was all the fuss about? And how accurate was the news coverage?

What was all the fuss about? And how accurate was the news coverage?

One of the most detailed reports was by Jennifer Pinkowski in The Washington Post (for those who prefer reading in Spanish, the article in BBC Mundo). I contributed to a Youtube video released by UCL TV, which summarises some of the relevant discussion (though sadly, the final cut does not present any actual data to substantiate our claims!), and was asked by China Daily to reflect on the implications of this study for modern staff management. Our research was highlighted among the top archaeology stories of 2012 according to the BBC. Many more international newspapers, websites and blogs reported and discussed our publication.

The academic paper in question was another contribution to our aim of understanding how technical knowledge, resources and labour were organised in order to make the First Emperor's Mausoleum. In particular, we presented a metric and chemical study of some 1600 of the 40,000 bronze arrowheads so far recovered from Pit 1 of the terracotta warriors. Based on the identification by portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry of chemical clusters that correspond to individual metal batches, and combined with a study of their context in the tomb complex, we argued that the manufacture of arrows was organised via a cellular production model with various multi-skilled units rather than as a single production line. This system favoured a more adaptable and efficient logistical organisation that facilitated dynamic cross-craft interaction while maintaining remarkable degrees of standardisation.

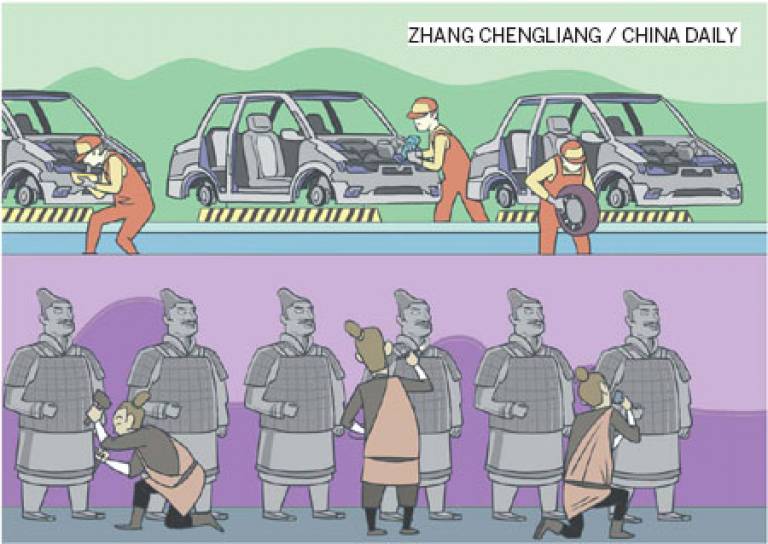

Why would media and the wider public be interested in this? Most media coverage focused on a comparison presented in our paper, which identifies some interesting parallels between the labour organisation model behind the construction of the Terracotta Army weapons some 2,200 years ago, and that employed at Toyota factories today. When we think of highly standardised, mass-produced, multi-component items, be they cars or terracotta warriors with their weapons, we tend to imagine a large production and assembly chain, broken down in small tasks performed by specialised units sometimes working in different locations. Different parts then join one another in a mechanised assembly line, as famously formalised by Henry Ford's car production and assembly lines in constant flow.

Toyota revolutionised car-making in the 1960s with an alternative logistical model structured in small cells of engineers who were on average more highly skilled, more autonomous, and ready to undertake any task as needed. Each Toyota-making cell is capable of making any car model more or less independently. Instead of producing large stocks of cars or parts thereof, they keep informed of production schedules and modify their plans accordingly, reducing downtime and adapting to the need or demand. They operate under a "lean manufacturing" management philosophy, a customer-oriented approach that strives to minimise waste while preserving product value. For example, "workers waiting" or "producing more than required" are considered waste. Even though individual cells may manufacture different products, they work in close cooperation and synchronise their output-as was perhaps the case with weapon- and warrior-making cells in the Terracotta Army. This production system, also known as "just in time" (cars are only produced where and when there is an order in place), has allowed Toyota to be much more adaptable to market fluctuations, and less susceptible to the knock-on effects caused by a breakdown in a given factory.

At the first emperor's mausoleum there was no market to adapt to, but there was a gigantic project of unpredictable evolution. Since nobody had tried to build a terracotta army before, there was no way of accurately predicting the number of items needed or the time it would take to produce them. Having a versatile workforce divided in cells capable of producing quiver-fulls of arrows or swords as needed, depending on the progression of the works, would increase efficiency and minimise the risks of a single delay stalling the whole enterprise.

Academic research and media coverage

Of course, we were careful to state that we did not imply a wider equivalence between the production systems behind terracotta warriors and Toyota cars. Our study was about understanding the organisational parameters behind the production of this colossal technological enterprise, and Toyota offered a useful reference in trying to explain why a cellular production model might have worked well in the context of the Qin logistics. Whatever the case, the Toyota-Terracotta comparison seems to have caught the popular imagination, inspiring colourful headlines such as "Terracotta Army makers beat Toyota by 2,200 years".

Is this a misrepresentation of our study? Does it harm our project? Certainly not. It simply capitalises on a finding of our research that was deemed to have a wider appeal. The claims made by the media are largely accurate, and the Toyota comparison has attracted public interest to our ongoing research. For specialists, and for anyone who would like to know more, there is a peer-reviewed publication detailing all the results and what we think are some of the more important implications.

If anything, we should perhaps have avoided the term 'Toyotism'

and used the more neutral 'Toyota Production System' instead, as a blog post saw

Marxist undertones in our use of the first term that were certainly not

intended. (Significantly, this feedback has been possible only by virtue of the

media dissemination).

Another frustrating aspect of media coverage is that journalists often quote a single spokesperson for the project, when the actual work has been carried out by a team. Even if I named people and institutions at every single interview, most journalists failed to find space for this.

On balance, however, we should be pleased that the wider public are getting some information out of our project. Some scientists and academics complain that the media do not provide precise accounts of their work, that they oversimplify the intricacies of their findings or overemphasise small headline-grabbing findings at the expense of more important issues. Others simply believe that their research is too complex or high-browed for the masses. I think this self-complacency helps no-one. Adapting the output of our research to a diverse range of target audiences, including 'laypeople', is not only inspiring and rewarding, but crucially fulfils our duty of giving something back to those whose heritage we study, and who ultimately sponsor the work that we enjoy doing.

Marcos Martinón-Torres is Professor of Archaeological Science at the UCL Institute of Archaeology and the Director of the Imperial Logistics Project.

Close

Close