Artificial virus created to help fight against superbugs

6 February 2020

An artificial virus capable of attacking superbug infections resistant to antibiotics has been bioengineered by researchers at UCL, NPL, University of Cambridge, University of Exeter and King’s College London.

The rise of superbugs is a serious concern in the medical community as bacteria evolve to evade existing treatments faster than new antibiotics can be developed. Rather than seeking out antibiotics that exist in nature, as has been the case with previous advances, the team of experts have designed one from the group up, inspired by viruses.

The findings, reported in ACS Nano, demonstrate how bioengineering and multi-modal measurements can offer and validate innovative solutions to healthcare, building on natural disease-fighting capabilities.

Maxim Ryadnov, Area Science Leader at NPL said: “Viruses are geometric objects. They are like solid cages built from tiny blocks glued together with an atomistic precision. We take that shape, strip off their viral proteins, and are left with a template.”

To pursue such a feat, this interdisciplinary research team adopted the geometric principles of the virus architecture to engineer a synthetic biologic – protein Ψ-capsid – which assembles from a small molecular motif found in human cells. This motif can recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns on bacterial surfaces but by itself is weakly antimicrobial. By contrast, each capsid, which comprises multiple copies of the motif, delivers an influx of high antimicrobial doses in its precise binding position on a bacterial cell.

Using a combination of nanoscale and single-cell imaging the team demonstrated that the capsids inflict irreparable damage to bacteria, rapidly converting into nanopores in their membranes and reaching intracellular targets. The capsids were equally effective in either of their chiral forms, which can render them invisible to the immune system of the host, killing different bacteria phenotypes and superbugs without cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo.

At UCL, the scientists visualised how the capsids landed on their targets and next created nanometre-size holes, which ultimately are lethal to the bacteria. Katharine Hammond, research scientist at NPL and PhD student at UCL Physics & Astronomy, said: "By scanning a sharp tip over the membrane surface, just like a miniature finger would read Braille, we could trace the contours of the capsids on the membranes and observe in real time how they punctured holes in their target membranes."

Ibolya Kepiro, Higher Research Scientist, National Physical Laboratory (NPL) stated: “This research culminates our joint efforts to identify an antibacterial mechanism that could be free from the frustration of bacterial persistence. We believe that these findings hold promise for the systemic assessment of antimicrobial efficacy”.

Links

- Research paper in ACS

- Professor Bart Hoogenboom’s academic profile

- London Centre for Nanotechnology

- UCL Physics & Astronomy

- UCL Mathematical & Physical Sciences

- UCL Institute for the Physics of Living Systems

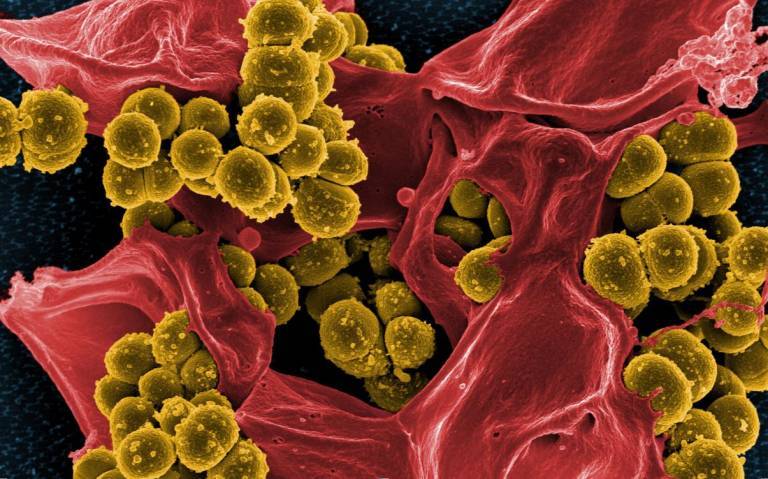

Image

- Scanning electron micrograph of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and a dead Human neutrophil (credit: NIAID, source: Wikimedia Commons)

Source

Media contact

Bex Caygill

Tel: +44 (0)20 3108 3846

Email: r.caygill [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close