Prion protein monoclonal antibody (PRN100) therapy for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

17 March 2022

A world-first treatment for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) has shown “very encouraging” early results following its use in six patients at University College London Hospitals (UCLH) NHS Foundation Trust.

The results, which are published in Lancet Neurology on the 16 March 2022, show the treatment is safe and able to access the brain. In three patients, the antibody may have stabilised disease progression when dosing levels were in target range.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob and other prion diseases are invariably fatal neurodegenerative conditions caused by prions – assemblies of misfolded host-encoded cellular prion protein (PrPC). No disease modifying treatments are available. While rare conditions, they are considered the paradigm for much commoner neurodegenerative dementias, notably Alzheimer’s disease. In prion disease, PrPC has been firmly validated as a target for drug development.

In an academic-led project, we made a fully humanised anti-PrPC monoclonal antibody (PRN100) and oversaw its manufacture to industry standard for human use. With the support of University College London Hospitals (UCLH) NHS Foundation Trust, which provided appropriate governance oversight, we treated patients with CJD under a “Specials” exemption.

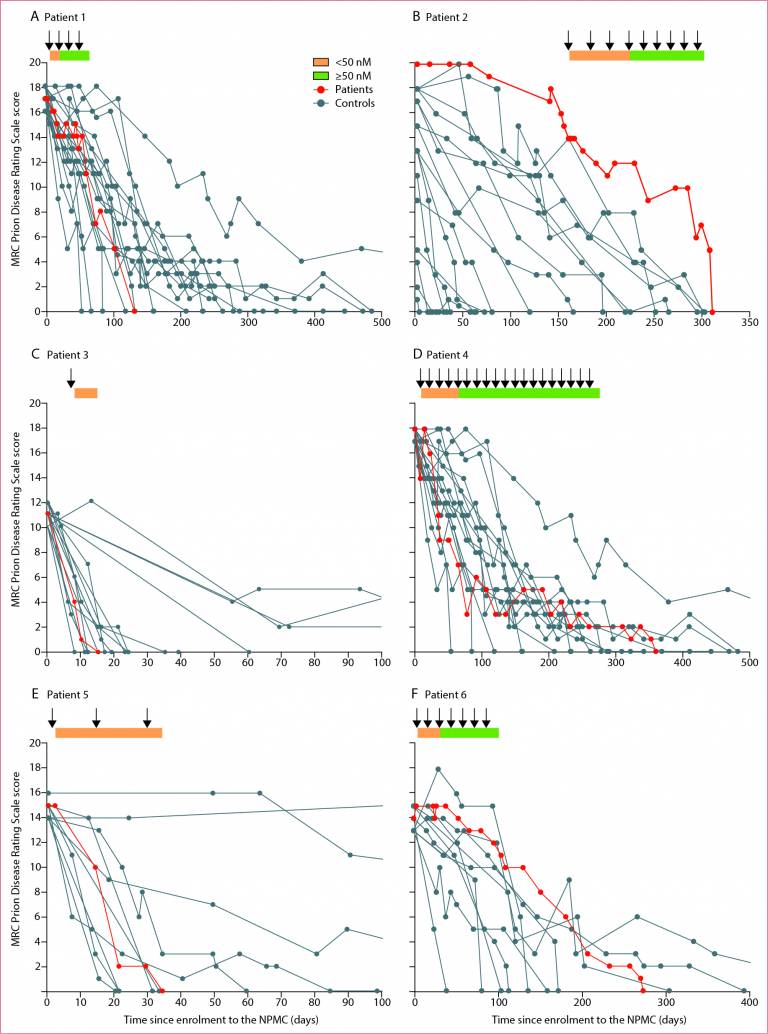

Six patients with CJD were treated with increasing doses of PRN100 by intravenous infusion and closely monitored for evidence of side effects; disease progression was assessed using clinical rating scales and compared with untreated patients in the National Prion Monitoring Cohort study, a clinical study led by the National Prion Clinic since 2008. Intravenous administration was safe and able to target the brain compartment. Repeated intravenous dosing of PRN100 was well tolerated and achieved CSF concentrations above the target amounts; no clinically significant side effects were seen. While in no patient was disease progression halted or reversed, in several patients clinical rating scale scores did appear to stabilise for periods when CSF drug levels were in the target range but the small numbers mean these are preliminary findings. Examination of a patient’s brain tissues after death showed no evidence of toxicity but marked drug effect with altered patterns of disease-associated PrP under the microscope.

This “Specials” treatment programme utilising a single batch of drug product could only be offered to a small number of patients with well-established neurological disease. The supply of drug is now exhausted. Our cautious dose escalation meant that it took an average of 47 days to reach target levels, a clinically significant period in a rapid disease like CJD. The safety profile, encouraging CSF and brain tissue levels following intravenous administration and preliminary clinical data justify moving onto larger trial in patients at the earliest possible clinical stage, before extensive brain damage is present. Further studies to establish if onset of disease can be prevented or delayed in healthy individuals iatrogenically infected with prions or harbouring pathogenic PRNP mutations may also be justified.

This approach to development and evaluation of a rational treatment for CJD may be of wider interest in assessment of therapeutics for other rare fatal diseases where there may no traditional business case for a pharmaceutical industry-led programme but a clear therapeutic target has been established.

Professor John Collinge, director of the MRC Prion Unit at UCL, who led the development of the PRN100 treatment, said: “Drugs intended for other diseases have been tried experimentally in treating CJD in the past but none has had an impact on disease progression or mortality.

“This is the first time in the world a drug specifically designed to treat CJD has been used in humans and the results are very encouraging.

“While the number of patients we treated was too small to determine whether the drug altered the course of the disease, this is nevertheless an important step forward in targeting prion infections.

“It has been a huge challenge to reach this milestone and we still have a long way to go but we have learned a great deal and these results now justify developing a formal clinical trial in a larger number of patients.”

Looking further into the future, Professor Collinge added: “We hope the drug may also have the potential to prevent the onset of symptoms in people at risk of prion disease due to genetic mutations or accidental prion exposure and may contribute to the development of therapies for more common dementias, such as Alzheimer’s disease.”

In a comment piece published alongside the results in the Lancet Neurology, Professor Inga Zerr, from the Department of Neurology at Georg-August University of Gottingen, Germany, also called for further studies in this area.

“These outcomes are very encouraging and long awaited but, in light of the limitations, such as the small number of patients included and the use of historical controls, these results must be considered preliminary,” she said.

Professor Bryan Williams, director of the National Institute for Health (NIHR) UCLH Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), said: “UCLH is a bold healthcare institution which, along with its academic partner UCL, is always seeking to push the frontiers of medicine and science to deliver innovative treatments to patients.

“Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rare and cruel disease which rapidly destroys the brain and for which there is currently no cure or licensed treatment. It was extremely important to us to find a way through the many challenges arising from the potential use of this novel treatment in order to offer it to a small group of patients.

“We are encouraged by the results which demonstrate the treatment is safe and there is some signal of benefit. The hope is that this could pave the way for new treatments of other neurodegenerative diseases.”

Close

Close