Managing risk in risky times

26 May 2022

Julia Kreienkamp and Tom Pegram explain why understanding complexity helps us get to grips with the risks around us.

The Covid-19 pandemic has powerfully demonstrated the fragility of our interconnected world, where a sudden shock can have unexpected ripple effects within and across systems, whether human, technological, or ecological. In such a context, existing risk governance structures, both public and private, are not fit for purpose when it comes to addressing complex global systemic risks, including much deadlier pandemics.

We argue that a deeper appreciation of risks as complex – as opposed to complicated – is now vital to effective risk governance.

Using Covid-19 as a case study, we developed novel design principles for risk governance intended to work with complexity, rather than against it. Our intention is to inform social science research and global policy efforts; however, our findings are also directly relevant to domestic policymakers who can no longer ignore the global, with broad application across substantive risk vectors, including climate change, food systems, cyber and geopolitics.

What do we mean by a complex risk landscape?

In an interconnected world, we face a growing number of complex risks that are systematically produced and amplified, some of which could pose serious, even existential, threats to human civilization. These risks are the endogenous product of interactive processes that are constantly evolving in unpredictable ways, making them uniquely difficult to contain. Yet, existing global governance structures and national crisis response mechanisms are still overwhelmingly geared towards managing complicated risks, where reasonable probabilities can be assigned, problems can be isolated and stabilised, and effective response strategies can be worked out in advance.

As a result, complex threats are misclassified and treated as complicated, resulting in ineffective, even counter-productive, attempts to impose a mechanical system logic onto problems that defy linear solutions.

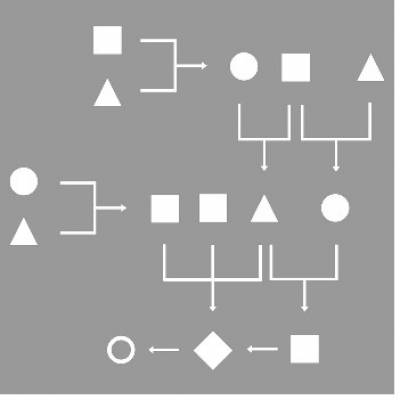

| Complicated risks arise out of closed systems, where the relationships between elements are static and clearly defined and linear cause-effect relationships can be established through in-depth investigation. As such, they can be addressed through expert-driven, top-down strategies, aimed at pareto-optimal solutions. |

| Complex risks arise out of open systems, capable of self-organising, where elements constantly interact with each other and their environment, giving rise to emergent behaviour and non-linear change. There are no optimal solutions and pathways forward may only emerge through observation, experimentation and experience. |

Of course, real-life governance challenges rarely fit neatly into either category.

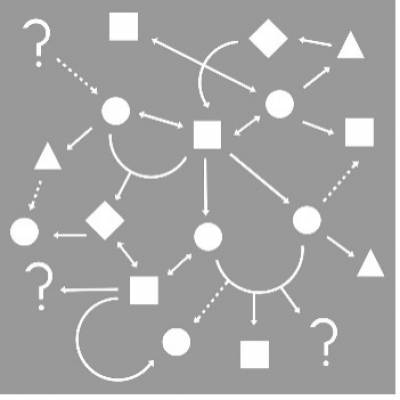

Most global risks simultaneously contain both complicated and complex elements. The ability to navigate such ‘restricted complexity’ – a world of unexpected surprises yet also displaying rule-bound regularities, recognisable patterns and hierarchies – is key to successful risk governance.

Complexity thinking can help us make sense of both the drivers and consequences of major infectious disease outbreaks such as COVID-19.

Growing global connectivity and increasing human encroachment on ecological systems have facilitated the emergence and spread of novel zoonotic diseases that jump from animals to humans. Unlike complicated risks, such as an aeroplane failure, pandemics cannot be fully understood in terms of linear causal chains. This is not to say that conventional governance logics break down completely. Expert-driven risk assessments and top-down interventions, including lockdowns, are key to viral containment. However, decision-makers must also contend with complex and evolving variables such as vaccine scepticism, underlying health inequalities, secondary effects of social distancing measures, or economic practices that promote the emergence of new zoonotic diseases while navigating a global politics riven with competing demands.

In other words, they operate in a domain of restricted complexity, where numerous known, unknown, and unknowable variables interact and risk governance becomes primarily a matter of building resilience, rather than preventing surprise.

COVID-19 has also exposed divisions on the global level, reifying the geopolitical battle lines at the World Health Organization (WHO) and severely limiting its ability to respond effectively to health emergencies.

On a deeper level, the pandemic highlights inadequacies of global governance design. As global problems have become more complex, governance structures at all levels have become ever-more complicated and, as a result, less resilient and increasingly maladaptive. These legacy structures urgently need supplementing with new mechanisms specifically geared towards complex task environments.

Against this background, we develop a set of systemic design principles for governing complex risk, aimed primarily at reforming multilateral organisations, but with broad applicability across levels of governance. These principles privilege effectiveness in the long run over short-term efficiency, recognising that optimisation in complex environments is not only impossible but also counterproductive. Rather, we emphasise the importance of continuous learning and bottom-up knowledge production through fail-safe experimentation, simultaneous probing of strategies, and feedback loops to correct failures and scale up success.

A deeper appreciation of complexity provides opportunities for policymakers to enhance the resilience of governance structures to ensure a more sustainable global response to the daunting challenges we confront within our increasingly globalised civilisation, where catastrophic failure anywhere could mean failure everywhere.

This blog is based upon Julia Kreienkamp and Tom Pegram (2021). ‘Governing Complexity: Design Principles for the Governance of Complex Global Catastrophic Risks’, International Studies Review, vol. 23(3), pp.779-806.

Julia Kreienkamp is Researcher at the UCL Global Governance Institute.

Dr Tom Pegram is Associate Professor in Global Governance and the Deputy Director of the Global Governance Institute.

Close

Close