Sabine Topf (UCL PALS PhD Student) studied the contents of bins at UCL. In this article, Sabine tells us about how the bin content was categorised and what she found.

How did you categorise the contents?

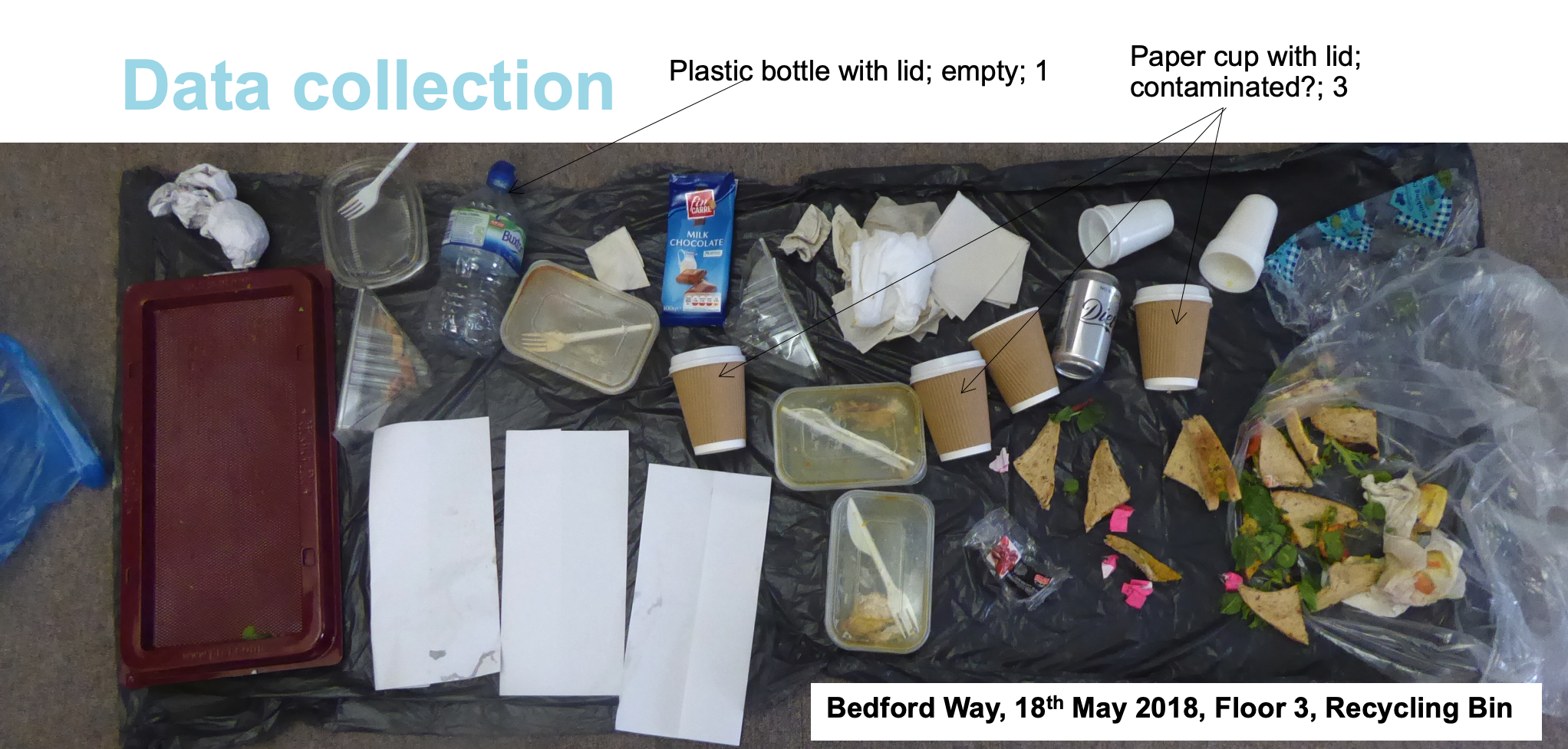

First of all, we photographed all items. Next, we checked whether the item could generally be recycled, depending on what material it was made of. For example, paper is recyclable (easy), crisp packets aren’t (did you know that? We didn’t before we had started the study). We then also looked at what state the item was in, for example whether it was wet, greasy or otherwise contaminated. For some recyclable items, contamination means that they are actually not recyclable. Finally, we also looked at whether an item was combined with other materials (e.g. a paper sandwich container with a plastic film window). This is important because when an items consists of both recyclable and non-recycable materials, these need to be separated before being disposed of. From those measures (recyclability, contamination, need for separation), we could tell whether an item was placed correctly in the bin we found it in.

First of all, we photographed all items. Next, we checked whether the item could generally be recycled, depending on what material it was made of. For example, paper is recyclable (easy), crisp packets aren’t (did you know that? We didn’t before we had started the study). We then also looked at what state the item was in, for example whether it was wet, greasy or otherwise contaminated. For some recyclable items, contamination means that they are actually not recyclable. Finally, we also looked at whether an item was combined with other materials (e.g. a paper sandwich container with a plastic film window). This is important because when an items consists of both recyclable and non-recycable materials, these need to be separated before being disposed of. From those measures (recyclability, contamination, need for separation), we could tell whether an item was placed correctly in the bin we found it in.

What did you find?

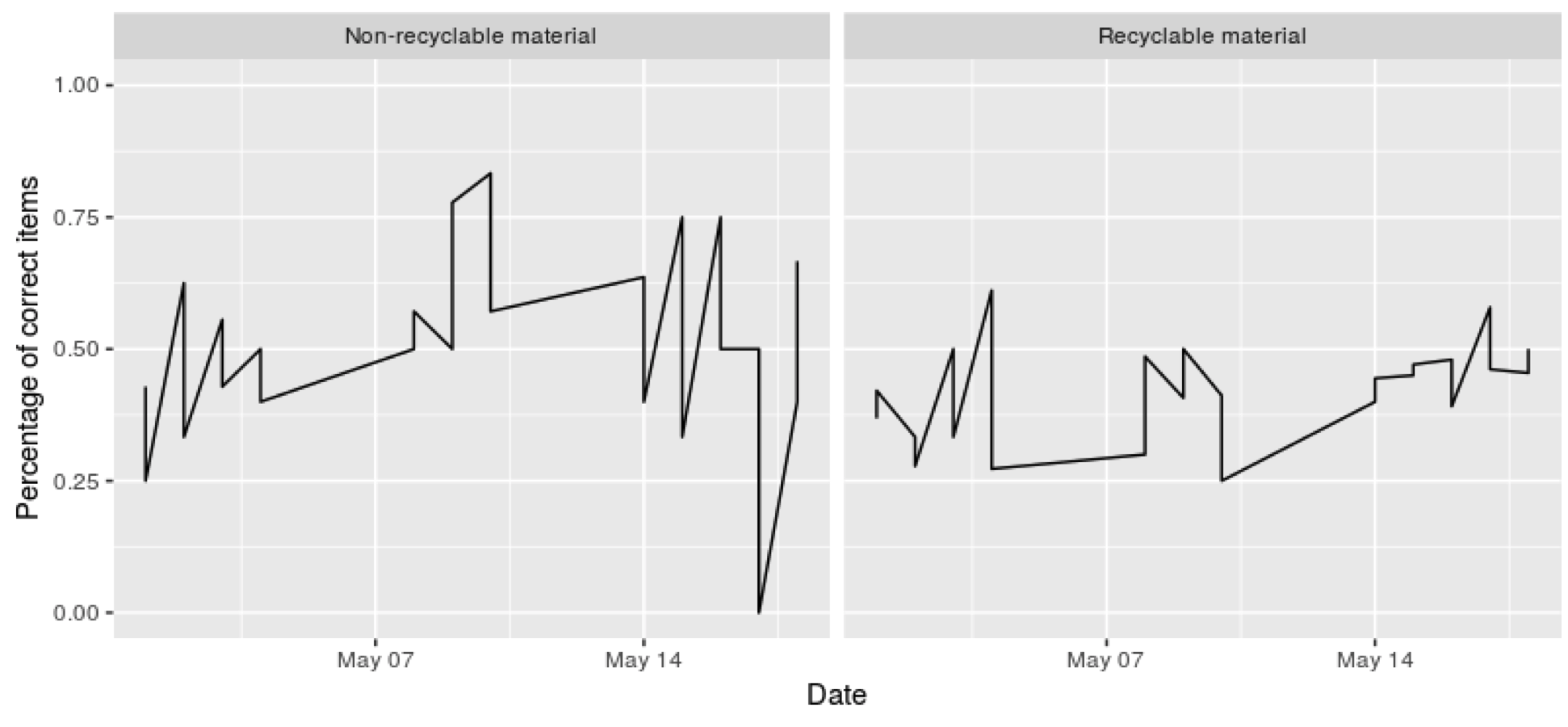

That sometimes psychological experiments work better with thick, yellow cleaning cloves! But more to the point, we found quite a mess. Often the contents of the bins were so random it was almost hard to tell which bin we had just categorised (see Figure 1). Overall correctness hovered around 50%. Not that great.

To be fair, some of this is not quite as bad as it looks. Some mistakes can be rectified at the recycling plant where some non-recyclable items can be sorted out. But this takes time and if there’s too many of them, a whole batch of recyclable items gets discarded because of that. Also, anything that lands in the non-recyclable bins but could be recycled won’t be recovered and therefore valuable resources are lost. Particularly bad are mistakes were an item contaminates other perfectly fine items – e.g., when a half-full coffee cup lands in the mixed-recyling bin, it could (and often will!) spill on paper and other materials that are now no longer recyclable (and we’re not even talking about how nasty it is for the well-meaning researcher rummaging in the bins).

What are we getting right? What are we getting wrong?

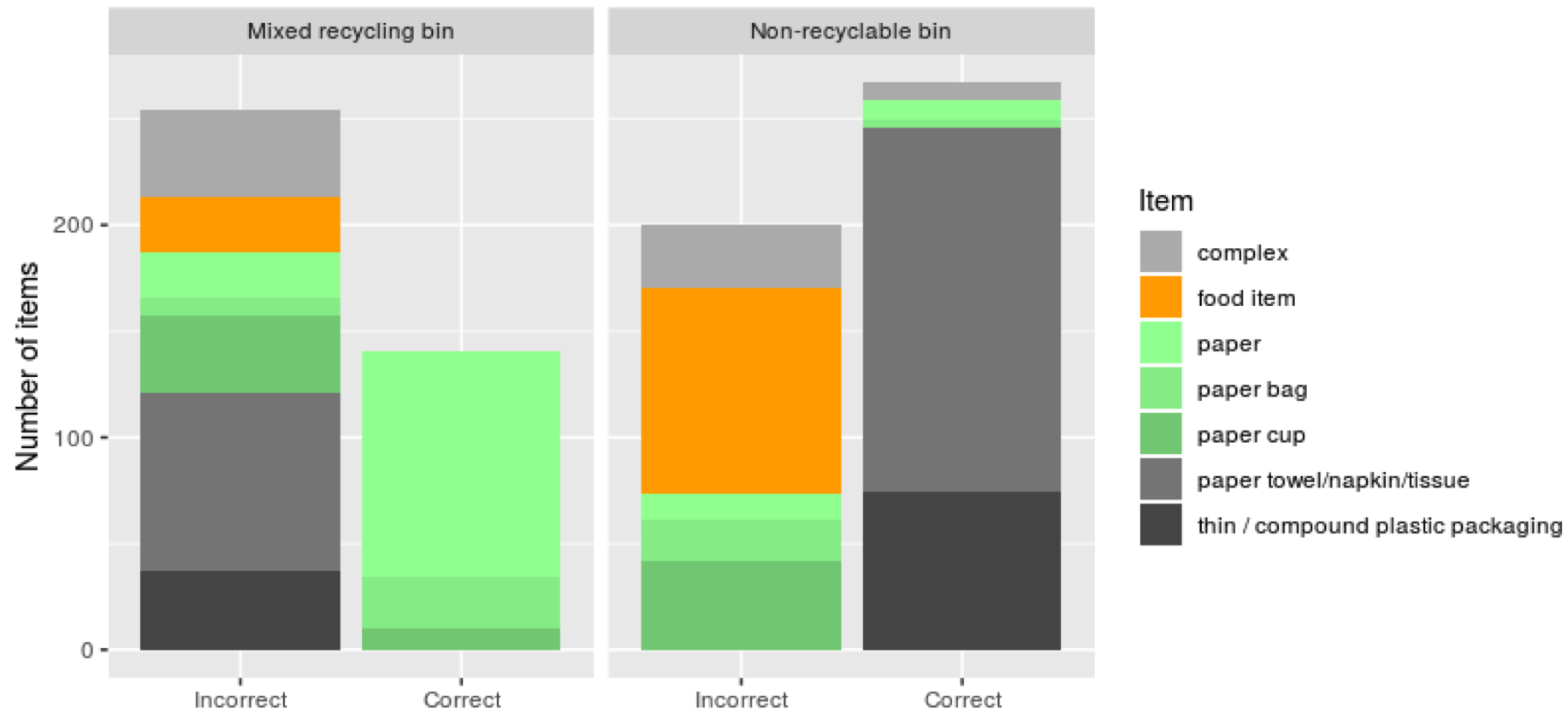

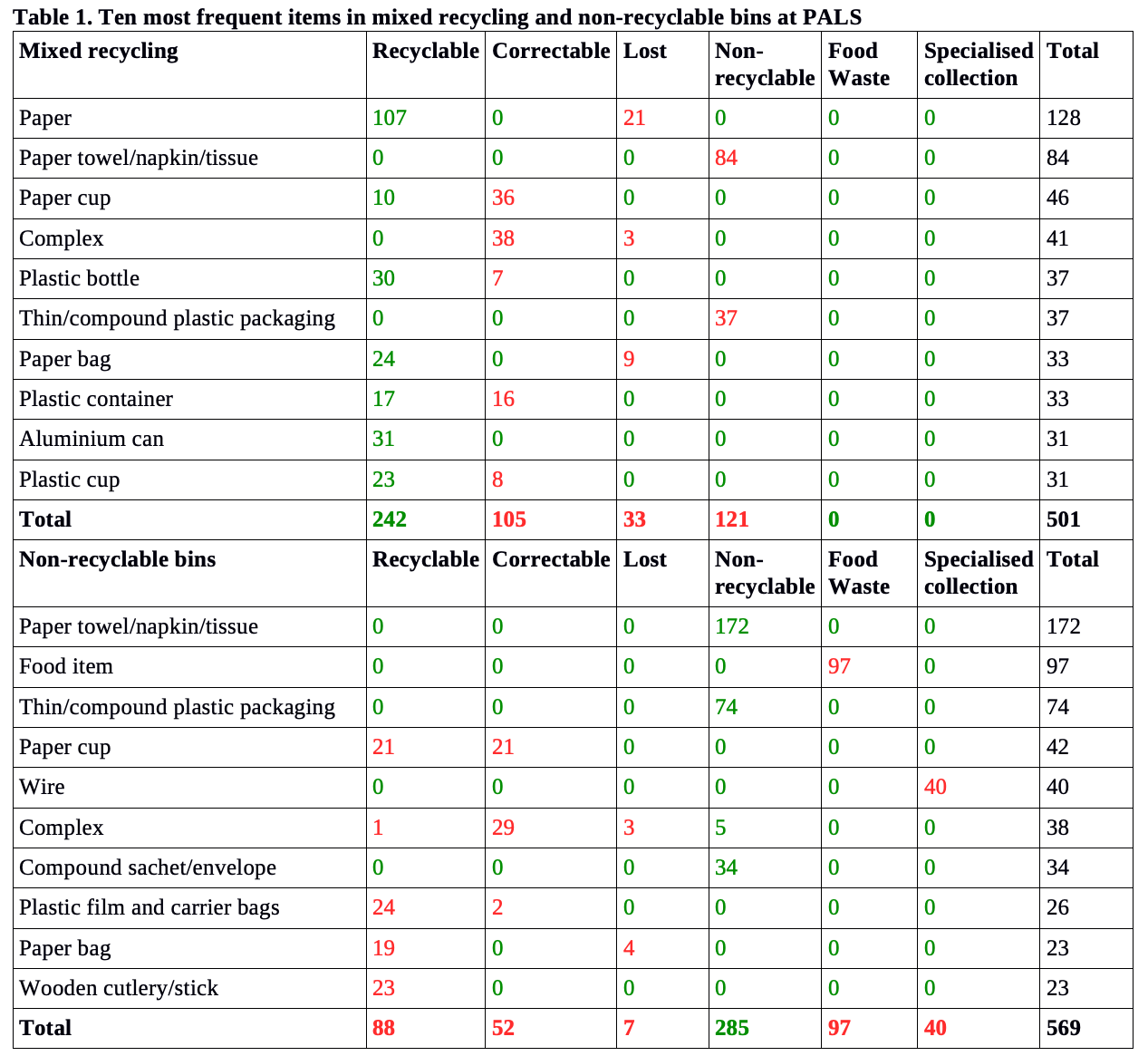

Overall we counted 1524 items at PALS (of 7472 overall). So PALS is contributing less waste than other locations (20%; we would expect 33% if all locations produced equal amounts). The most common item categories at the two locations at PALS can be seen in Figure 2. First, what stands out here are the high number of food items in both mixed recyling and non-recylable bins. This is especially puzzling because with all UCL bins, there is a food waste bin right next to the others.

But even for relatively easy items, things quickly get complicated. For example, paper (light-green), is generally placed in the correct bins (mixed recycling, that is), or in the non-recyclable bin when it has been contaminated. But even though this is an easily categorised item, it sometimes lands in the non-recylable bins and – unfortunately – gets contaminated in the mixed recycling bins.

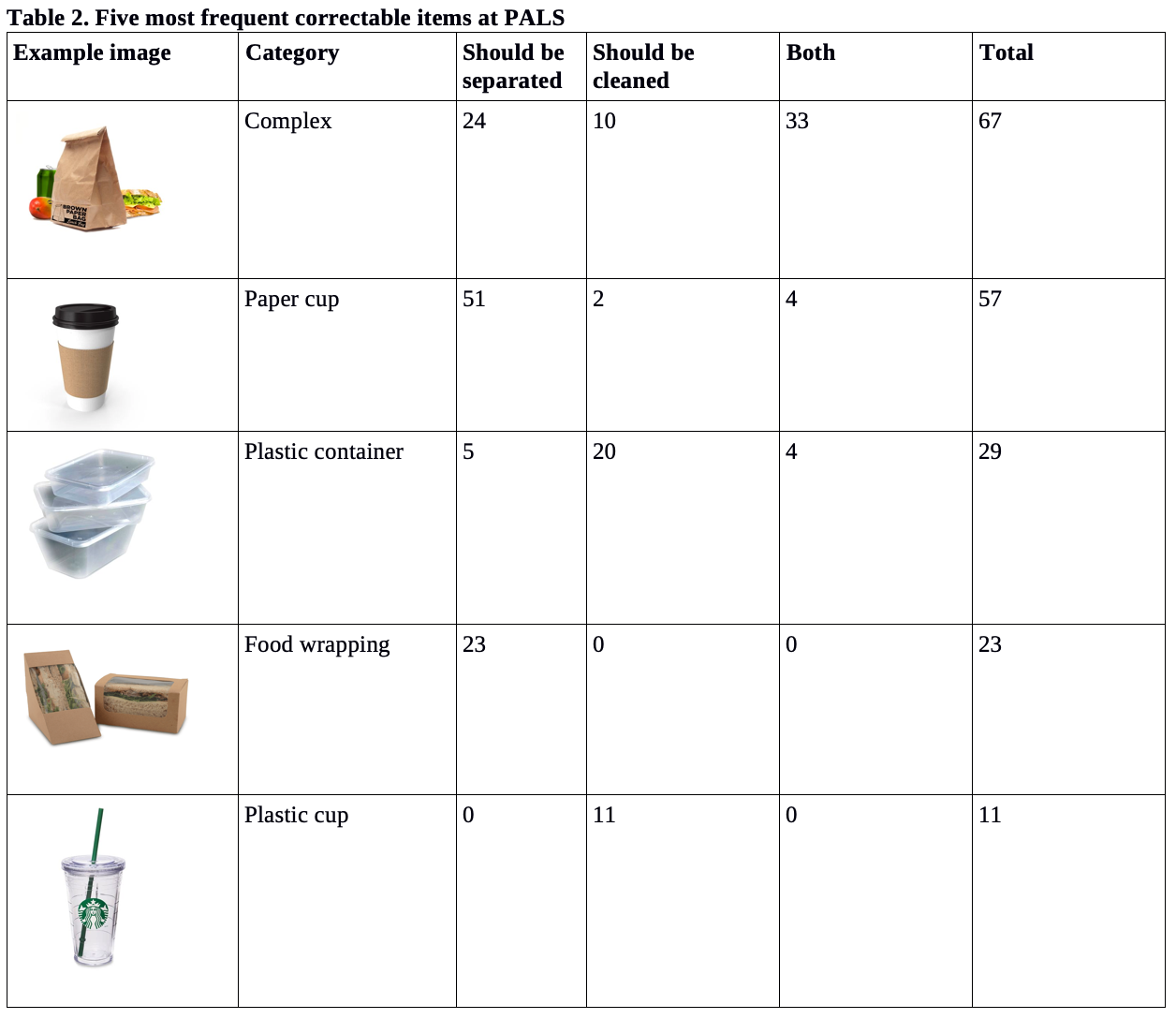

To better understand what’s going on in, we need to look at the other measures we used: Contamination and Need for Separation. Table 1 below shows the ten most frequent items at PALS, again split by which bin we found them in. Correctable means that these items could go in the recycling bin, if they had been cleaned or separated from non-recyclable materials. Lost means items that would have been recyclable but are contaminated to a degree where cleaning is no longer possible. Together, these make the second most frequent category (or 28% of items) in the mixed recycling bin. They are less frequent in the non-recyclable bin but still a substantial amount (10%).

Clean & separate!

The most common items at PALS that could be corrected are food related items. For example, most plastic containers could be recycled if they had been cleaned. This does not need to be perfect – often it’s enough to separate left-over foods (which should go in the food waste bin) from the container.

What goes where? Tips regarding the most commonly misplaced items at PALS

This should go in the non-recyclable bin:

- Snack wrappers, crisp packets and anything else that looks like a bag that has been lined with foil should go in the non-recyclable bin. What looks like foil is a type of plastic that cannot be recycled.

- Plastic film (e.g. cling film) and carrier bags (and other thin/soft plastic) should also go in the non-recyclable bin.

- ‘Compostable’ items (e.g., containers and cutlery) should go in the non-recyclable bin. As tempting (and logical) as it may seem to put them in the food waste, commercial composting is too slow a process to deal with these allegedly ‘compostable’ items (this includes wooden items!).

- Paper cups should also go in the non-recyclable bin because they are lined with a thin layer of plastic to keep the liquids in which makes them non-recyclable. When there are separate dedicated cup bins available (currently in selected cafes only), please dispose of your cup there. Or even better: Get a reusable one!

This should go in the mixed recycling bin:

- Paper items (such as paper bags), the grandmothers of recyclable items, are more than welcome in the mixed recycling bin.

- Paper towels/napkins/tissues (thin/soft paper products) can be recycled, but only if they aren’t excessively wet or contaminated (try the squeeze test – does liquid come out of it? Then it can’t be recycled).

Close

Close

Check out the Green Impact Team's

Check out the Green Impact Team's