Unlocking the blood-nerve barrier to facilitate drug delivery

8 June 2023

A UCL-led research team has opened and closed the blood-nerve barrier for the first time and used it to deliver drugs to target tissues.

The Medical Research Council and Cancer Research UK-funded research, published in Developmental Cell, has the potential to both deliver tumour-killing drugs to the nervous system, and also prevent side effects from chemotherapy that result from damage to the peripheral nervous system.

The blood-nerve barrier is less well understood than the related blood-brain barrier, which stop substances in the blood getting to the sensitive environments of the brain and peripheral nerves. They also pose a barrier for medications, so the latest study has been seeking to identify new ways to deliver drugs to the nervous system, without causing damage.

Lead author Professor Alison Lloyd, director of the UCL Laboratory for Molecular Cell Biology, explained: “We’ve defined the structure and control of the blood-nerve barrier – the cell types that are involved, how they interact, how it can be regulated and why it’s a barrier. It took more than 10 years of development, but we now have a powerful model that enables us to control and understand the opening and closing of the barrier.

“Our discovery that the barrier can be opened in a reversible manner is important in the drive to deliver drugs to the nervous system, as permanently breaking down these barriers would be toxic. We’ve shown you that can help drugs cross the barrier for a limited time, which makes side effects less likely.”

For the study, Professor Lloyd and her colleagues established the structure and function of the blood-nerve barrier, finding that it is ‘leakier’ than the blood-brain barrier, but reinforced by macrophages (a type of white blood cell) that specifically engulf leaked materials.

Using these insights, the researchers devised a way to set off a signal to open the barrier in a mouse model for enough time to deliver drugs called antisense oligonucleotides, to the peripheral nervous system.

Although at its early stages, the researchers say their paper is important for neuroscience as getting past the blood-nerve barrier could make it easier to treat a wide variety of conditions. For example, chemotherapy treatment in cancer can have an unpleasant side-effect called peripheral neuropathy, where people feel burning, tingling or numbness in their hands and feet because of damage to the peripheral nerves. This research may contribute to the development of drugs that could be added into chemotherapy treatment to minimise such side-effects.

This research also has much wider application beyond cancer. Diabetes can also cause peripheral neuropathy so the knowledge from this research could make it much easier to manage diabetes in the future. The drugs used in this study, antisense oligonucleotides, are currently in trials for diseases like Huntington’s and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, so there is potential for better care for multiple difficult-to-treat diseases.

Links

- Research paper in Developmental Cell

- Cancer Research UK feature article

- Professor Alison Lloyd’s academic profile

- UCL Laboratory for Molecular Cell Biology

Image

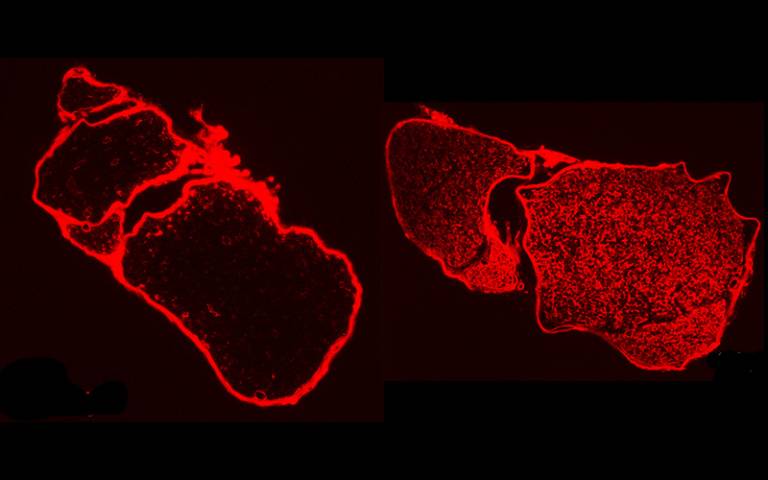

- Drugs (red spots) don’t get into peripheral nerves when the barrier is closed (left-side image) - only when the barrier is opened (right-side image). Image courtesy Prof Lloyd.

Media contact

Chris Lane

Tel: +44 (0)207 679 9222

Email: chris.lane [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close