Feature: The ‘historic’ Alzheimer’s breakthrough that is 30 years in the making

2 December 2022

UCL’s Professor Sir John Hardy was the first to identify the role of amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease - now, three decades later, that finding has resulted in a drug that may help patients.

In newly published trial results, a drug has for the first time been shown to slow the rate of cognitive decline in people with Alzheimer’s disease. The drug, lecanemab, was found to have a modest effect in treating the disease, but its implications have been hailed as momentous – marking a turning point in Alzheimer’s research and giving hope to millions across the globe.

The news is particularly poignant for Professor Sir John Hardy (UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology), as it represents a lifetime of work, by supporting a hypothesis that he first developed 30 years ago.

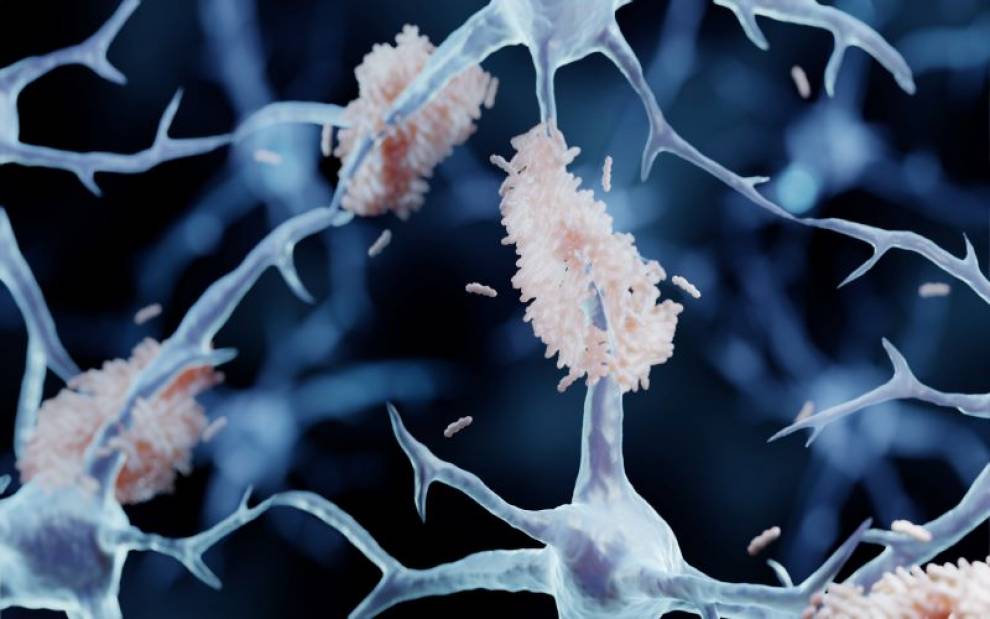

Lecanemab works by targeting beta amyloid – a plaque that builds up in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

This was an idea pioneered by Professor Hardy when he began working with Carol Jennings and her family.

Carol reached out to Professor Hardy in the mid-1980s, after her father, his sister and brother all developed symptoms and were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in their 50s.

Professor Hardy said: “Throughout her family were people who developed Alzheimer’s and did so in their 50s, and she wanted answers. She’s a very determined woman, a remarkable woman.”

Genetic Alzheimer’s is rare and only accounts for around 1% of Alzheimer’s cases. However, Professor Hardy believed that Carol’s family could unlock clues as to the cause of the condition in the wider population.

Intrigued, he and his team took blood samples from members of the Jennings family to identify if there were any genetic differences between those who had Alzheimer’s and those who didn’t.

After five years of research, the team discovered a mutation to the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, which creates the amyloid plaques that form in the brain during Alzheimer’s disease.

Amyloid affects brain cells by causing them to become overactive and signalling for ongoing inflammation, which can disrupt normal processes in the brain.

Blood flow can also be affected and other proteins in the brain can become involved. For example, when too much amyloid is deposited, it can react with another toxic protein called tau, which causes neuronal death.

In those with genetic Alzheimer’s this happens early because the patient makes too much APP. However, it also happens in those with non-genetic Alzheimer’s but at a slower rate.

As a result of these findings, in 1992, Professor Hardy and his colleague Professor David Allsop published the amyloid cascade hypothesis, which they hoped would “facilitate rational design of drugs to intervene in this process.”

The theory helped to explain the three key features seen in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease, including the brain appearing smaller due to the death of brain cells, the build-up of amyloid protein and tangles with tau.

From that point, there was a drive to understand more about Alzheimer’s and other dementias, with Professor Hardy winning the $3million Breakthrough prize in life sciences in 2015.

Professor Hardy was also knighted in the 2022 New Year Honours for services to “human health in improving our understanding of dementia and neurodegenerative diseases”.

And the clinical team at the Dementia Research Centre (DRC) at UCL, which was previously led by Dr Martin Rossor, and is now led by Dr Cath Mummery and Professor Nick Fox (all Queen Square Institute of Neurology), have been at the forefront of research into the condition and its causes.

Over the years, the amyloid cascade hypothesis was built upon, modified, and challenged by researchers. However, the development of anti-amyloid drugs continually proved to be difficult.

For example, in 2021, the drug aducanumab was approved by the US drug regulatory body, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), for use to combat early Alzheimer’s.

However, it was later refused by the European Medicines Agency on the basis that results from the main clinical studies were conflicting and did not show overall that aducanumab was effective at treating adults with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease.

Some studies also questioned the safety of the drug, as images from brain scans of some patients showed abnormalities suggestive of swelling or bleeding.

However, the latest large-scale trial of lecanemab – which was tested on 1,795 volunteers with early stage Alzheimer’s - has given a new glimmer of hope.

The results, which were presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference in San Francisco and published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that, when given every fortnight, lecanemab slowed cognitive decline by around a quarter (27%) over the course of the 18 months of treatment.

This is an outcome that Professor Hardy describes as being both “modest” and “historic”.

Professor Hardy said: “This trial is an important first step, and I truly believe it represents the beginning of the end. The amyloid theory has been around for 30 years so this has been a long time coming.

“It’s fantastic to receive this confirmation that we’ve been on the right track all along, as these results convincingly demonstrate, for the first time, the link between removing amyloid and slowing the progress of Alzheimer’s disease.

“The first step is the hardest, and we now know exactly what we need to do to develop effective drugs. It’s exciting to think that future work will build on this, and we will soon have life-changing treatments to tackle this disease.

“The trial results have shown us that there is a risk of side effects, including brain bleeds in a small number of cases. This doesn’t mean the drug can’t be administered, but that will be important to have rigorous safety monitoring in place for people receiving lecanemab, and further trials to fully understand and mitigate this risk.”

The data is now being assessed by regulators in the US, who will soon decide whether lecanemab can be approved for wider use. And the developers – Eisai and Biogen – hope to begin the approval process in other countries next year.

Looking back over the past 30 years of research and the progress that has been made, Professor Hardy added: “Today marks a truly exciting day for dementia research. I’m incredibly proud of how far we’ve come since our Alzheimer’s Society funded research in 1989, which showed for the first time that a toxic protein called amyloid played a role in the cascade of brain changes leading to Alzheimer’s disease.

“This discovery would not have been possible without the selfless dedication of families affected by dementia who took part in this research.

“A drug like lecanemab becoming available on the NHS would be a massive triumph, but challenges remain around getting drugs to the right people at the right time – we need changes in our health systems infrastructure to make sure we’re ready.”

Links

- Professor Sir John Hardy's academic profile

- Professor Nick Fox's academic profile

- Professor Martin Rossor's academic profile

- Dr Cath Mummery's academic profile

- UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology

- UCL Brain Sciences

- Dementia Research Centre at UCL

- Lecanemab research in The New England Journal of Medicine

- The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis

Image

- Amyloid plaques are misfolded protein aggregates between neurons - Alzheimer's disease illustration. Credit: Artur Plawgo on iStock

Media contact

Poppy Danby

E: p.danby [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close