Solar Orbiter’s first images reveal ‘campfires’ on the Sun

16 July 2020

The first images from Solar Orbiter, a Sun-observing mission by ESA and NASA carrying instruments proposed, designed and built at UCL, reveal omnipresent miniature solar flares near the surface of our closest star.

One unique aspect of the Solar Orbiter mission is that no other spacecraft has been able to take images of the Sun’s surface from a closer distance.

The miniature flares seen in the new images were not observable in detail before, hinting at the enormous potential of Solar Orbiter in helping scientists piece together how the Sun’s atmospheric layers interact and drive the solar wind. This knowledge is vital for understanding how the Sun drives space weather events, which can disrupt and damage satellites and infrastructure on Earth.

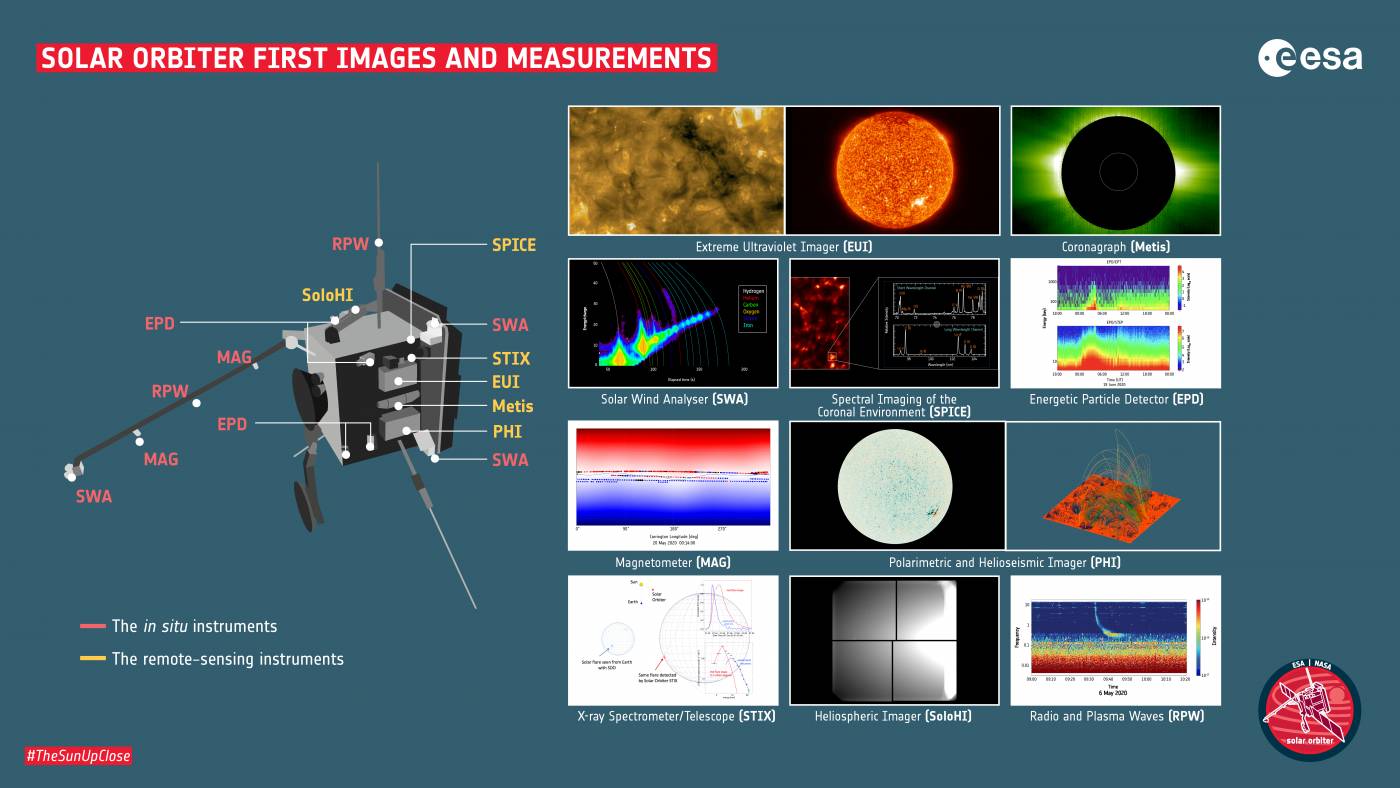

Launched in February 2020, Solar Orbiter carries six remote sensing instruments, or telescopes, that image the Sun and its surroundings, and four in-situ instruments that measure properties of the environment around the spacecraft. By comparing the data from both sets of instruments, scientists will gain insights into the generation of the solar wind, the stream of charged particles from the Sun that influences the entire Solar System.

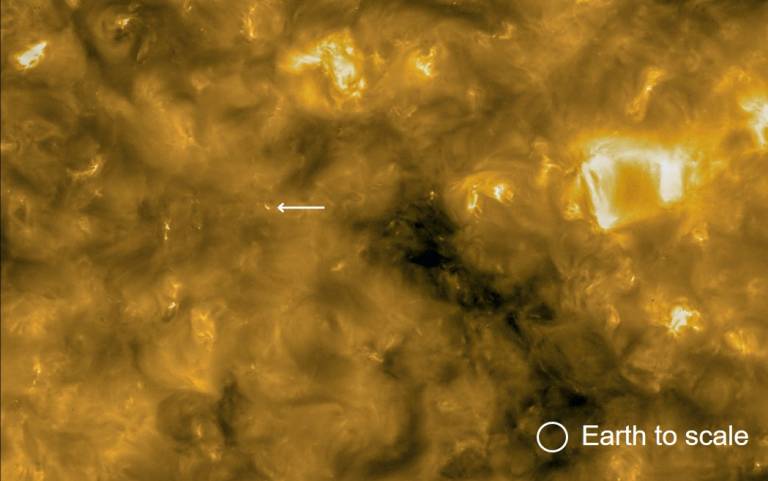

The ‘campfires’ shown in the first image set were captured by the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) around Solar Orbiter’s first perihelion, the point in its elliptical orbit closest to the Sun, in mid-June. At that time, the spacecraft was only 77 million kilometres away from the Sun, about half the distance between Earth and the star.

UCL is a Co-Principal Investigator for EUI – a suite of telescopes that provide images of the hot and cold layers of the Sun’s atmosphere and corona, showing the dynamics in fine detail and providing the link between the Sun’s surface and outer corona.

Dr David Long (UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory), Co-Principal Investigator on the ESA Solar Orbiter Mission EUI Investigation, said: "No images have been taken of the Sun at such a close distance before and the level of detail they provide is impressive.

“They show miniature flares across the surface of the Sun, which look like campfires that are millions of times smaller than the solar flares that we see from Earth. Dotted across the surface, these small flares might play an important role in a mysterious phenomenon called coronal heating, whereby the Sun's outer layer, or corona, is more than 200 - 500 times hotter than the layers below.

“We are looking forward to investigating this further as Solar Orbiter gets closer to the Sun and our home star becomes more active."

The solar corona is the outermost layer of the Sun’s atmosphere that extends millions of kilometres into outer space. Its temperature is more than a million degrees Celsius, which is orders of magnitude hotter than the surface of the Sun, a ‘cool’ 5500 °C. After many decades of studies, the physical mechanisms that heat the corona are still not fully understood, but identifying them is considered the ‘holy grail’ of solar physics.

“It’s obviously way too early to tell but we hope that by connecting these observations with measurements from our other instruments that “feel” the solar wind as it passes the spacecraft, we will eventually be able to answer some of these mysteries,” said Dr Yannis Zouganelis, Solar Orbiter Deputy Project Scientist at ESA.

Today’s release highlights Solar Orbiter’s imagers, but its four in-situ instruments also revealed initial results. This includes the UCL-led Solar Orbiter's Solar Wind Analyser, or SWA instrument, which shared the first dedicated measurements of heavy ions (carbon, oxygen, silicon, iron, and others) in the solar wind from the inner heliosphere.

Prof Christopher Owen (UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory), Principal Investigator of SWA, said: “Heavy ion populations change little during the transport of the solar wind from the Sun to the spacecraft, making them an excellent diagnostic of the nature of those ions in the corona.

“We can estimate where on the Sun that particular part of the solar wind was emitted, confirm that using our measurements and then use the full instrument set of the mission to reveal and understand the physical processes operating in the different regions on the Sun which lead to solar wind formation.”

The spacecraft, now in its cruise phase with the in-situ instruments in routine operation, is gradually adjusting its orbit around the Sun. Once in its nominal science phase, which will commence in late 2021, the spacecraft will get as close as 42 million kilometres from the Sun’s surface, closer than the planet Mercury. At this point the remote sensing instruments will start regular period of observation. Moreover, the spacecraft’s operators will gradually tilt Solar Orbiter’s orbit to enable the probe to get the first proper view of the Sun’s poles.

Science Minister Amanda Solloway said: “The Solar Orbiter was eight years in the making, and represents an incredible feat for UK engineering. A UK-built craft is now in space, withstanding the harshest environment and solar radiation 13 times more powerful than in the Earth’s orbit.

“This mission is our most important UK space science venture for a generation and as we grow our status as a space power in the years to come, the achievements and discoveries from the Solar Orbiter mission shows the world what we are capable of.”

Links

- ESA Solar Orbiter

- ESA announcement

- UK Space Agency announcement

- Dr David Long's academic profile

- Professor Chris Owen's academic profile

- UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory

- UCL Space & Climate Physics

- UCL Mathematical & Physical Sciences

Images

Solar Orbiter spots ‘campfires’ on the Sun: A high-resolution image from the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) on ESA’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft, taken with the HRIEUV telescope on 30 May 2020. The circle in the lower right corner indicates the size of Earth for scale. The arrow points to one of the ubiquitous features of the solar surface, called ‘campfires’ and revealed for the first time by these images. On 30 May, Solar Orbiter was roughly halfway between the Earth and the Sun, meaning that it was closer to the Sun than any other solar telescope has ever been before. Credit: Solar Orbiter/EUI Team (ESA & NASA); CSL, IAS, MPS, PMOD/WRC, ROB, UCL MSSL

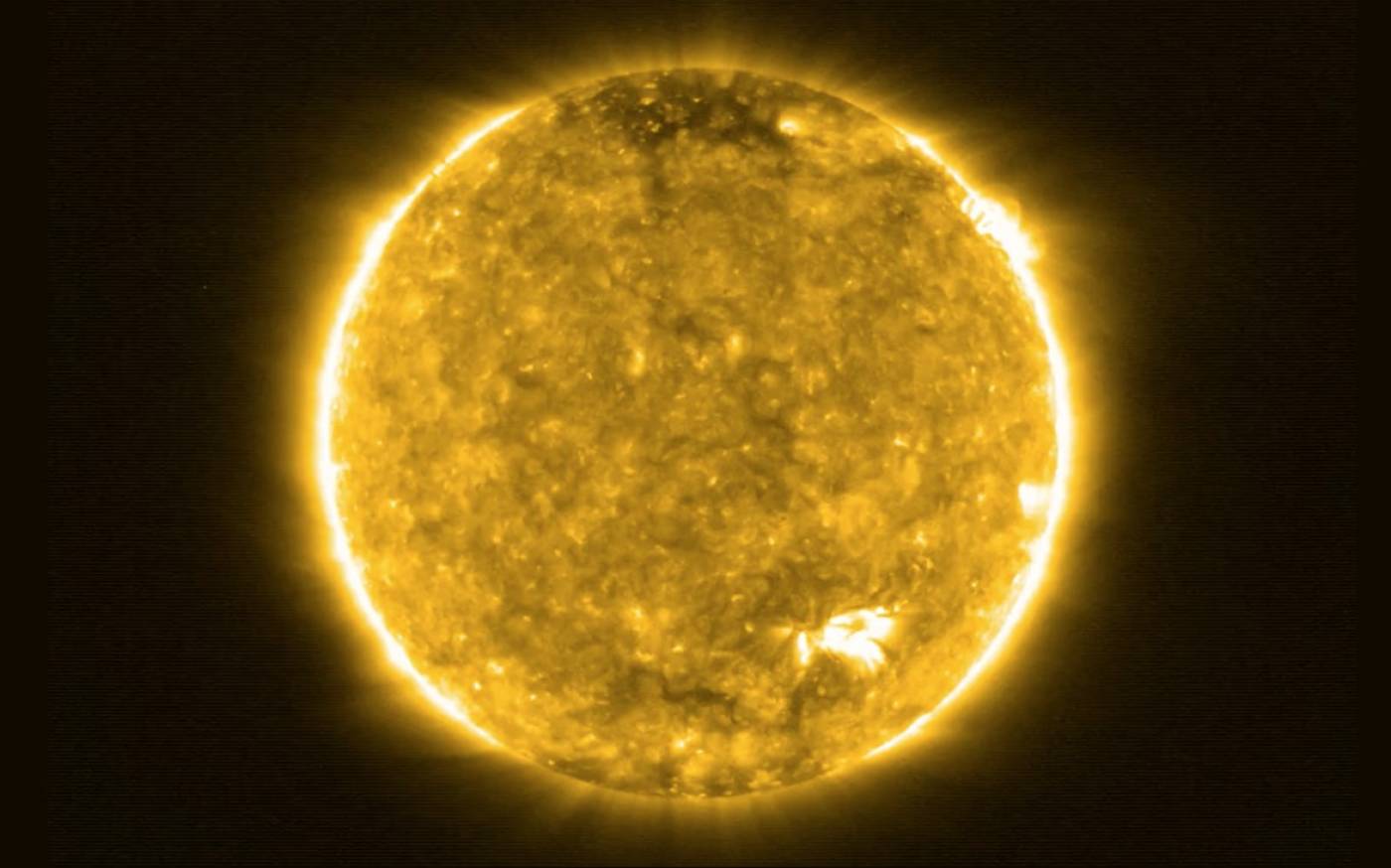

Solar Orbiter’s first view of the Sun: The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) on ESA’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft took these images on 30 May 2020. They show the Sun’s appearance at a wavelength of 17 nanometers, which is in the extreme ultraviolet region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Images at this wavelength reveal the upper atmosphere of the Sun, the corona, with a temperature of around 1 million degrees. EUI takes full disk images using the Full Sun Imager (FSI) telescope. The colour on this image has been artificially added because the original wavelength detected by the instrument is invisible to the human eye. Credit: Solar Orbiter/EUI Team (ESA & NASA); CSL, IAS, MPS, PMOD/WRC, ROB, UCL MSSL

Media contact

Bex Caygill

Tel: +44 (0)20 3108 3846

Email: r.caygill [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close