Asteroid impact, not volcanic eruptions, killed the dinosaurs

16 January 2020

Volcanic activity did not play a direct role in the mass extinction event that killed the dinosaurs and about 75 per cent of Earth’s species 66 million years ago, according to a team involving UCL and University of Southampton researchers.

Two planetary-scale disturbances occurred within less than a million years of one another, leading scientists to question the role each played in driving the mass extinction event: An asteroid more than 10 km in diameter collided with the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico creating the 200 km wide Chicxulub impact crater and around the same time about 500,000 km3 of lava flooded across much of India and into the deep sea forming the Deccan Traps, one of the largest volcanic features on Earth.

In a Yale-led study, published today in Science, analysis of marine fossils and climate models shows that the major release of volcanic gasses, thought by some to contribute to the extinction, happened about 200,000 years before the asteroid impact, making the asteroid the sole driver of the extinction event.

“Most scientists acknowledge that the last, and best-known, mass extinction event occurred after a large asteroid slammed into Earth 66 million years ago, but some researchers suggested volcanic activity might have played a big role too and we’ve shown that is not the case,” explained co-author, Professor Paul Bown (UCL Earth Sciences).

The researchers searched for evidence for a correlation in timings between volcanic eruptions and the mass extinction event, known as K-Pg, and found none.

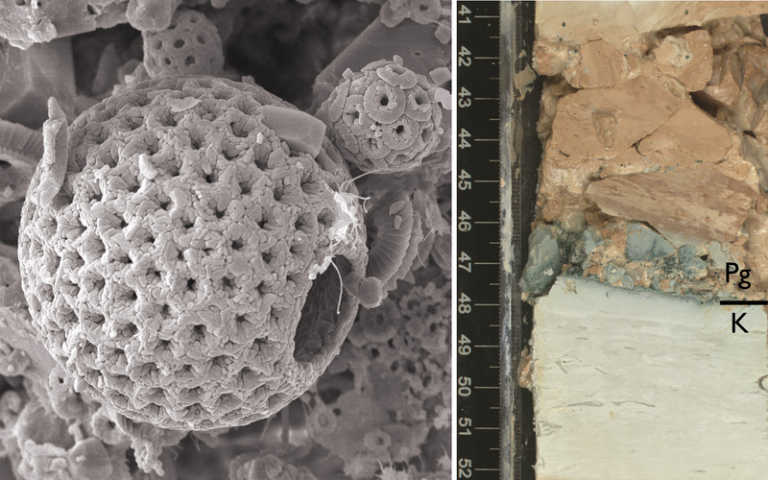

They did this by studying the environmental impacts from massive volcanic eruptions in India, which formed the Deccan Traps plateau. They looked at ocean temperature and carbon cycle changes around the time of the extinction event using microscopic marine fossils, and compared these records to models of the climatic effect of carbon dioxide release. This pinpointed the timing of the volcanic gas emissions to 200,000 years before the extinction event.

Dr Pincelli Hull (Yale), lead author of the study, said: “Volcanoes can drive mass extinctions because they release lots of gases, like sulphur dioxide and carbon dioxide, that can alter the climate and acidify the world, but recent work has focused on the timing of lava eruption rather than gas release.”

Professor Paul Wilson (University of Southampton), who led the International Ocean Discovery Program expedition, said: “By focusing on the effects of the gases that were released, rather than dating the rocks left behind by the Deccan eruptions, we found that volcanism began and ended distinctly prior to the mass extinction while the impact event coincides with the extinction. This means volcanoes are not a driver in the mass extinction event.”

They found that volcanic activity in the Late Cretaceous caused only a gradual global warming of about two degrees, but from analysing deep-sea sediment sections drilled from the North Atlantic, Pacific and South Atlantic Oceans, this warming had no significant effect on marine ecosystems, and cooler conditions had returned prior to the extinction.

“A lot of people have speculated that volcanoes mattered to the K-Pg event, and we’re saying, ‘No, they didn’t,’” added Dr Hull.

Recent work on the Deccan Traps has also pointed to massive eruptions in the immediate aftermath of the K-Pg mass extinction. These results have puzzled scientists because there is no warming event to match. The new study suggests an answer to this puzzle, as well.

“The K-Pg extinction was a mass extinction and this profoundly altered the global carbon cycle,” said co-author postdoctoral associate Donald Penman (Yale). “Our results show that these changes would allow the ocean to absorb an enormous amount of CO2 on long time scales — perhaps hiding the warming effects of volcanism in the aftermath of the event.”

Researchers from UCL, the University of Southampton, University of Edinburgh and the Open University form part of a multinational team of scientists that drilled and studied a new K/Pg boundary section in the North Atlantic through the NERC-funded Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 342.

The wider team includes researchers from institutions in Germany, France, Spain, Japan, Denmark and the USA. The International Ocean Discovery Program, the National Science Foundation, and Yale University helped fund the research.

Links

- Research paper in Science

- Professor Paul Bown's academic profile

- UCL Earth Sciences

- UCL Mathematical & Physical Sciences

Image

- Nannoplankton fossils next to a deep-sea sediment section drilled from the North Atlantic (credit: Professor Paul Bown)

Media contact

Bex Caygill

Tel: +44 (0)20 3108 3846

Email: r.caygill [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close