Virtual reality can spot navigation problems in early Alzheimer’s disease

24 May 2019

Virtual reality (VR) can identify early Alzheimer’s disease more accurately than ‘gold standard’ cognitive tests currently in use, suggests new research from UCL and the University of Cambridge.

The study, published in Brain, highlights the potential of new technologies to help diagnose and monitor conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, which affects more than 525,000 people in the UK.

“Recent studies have shown that Alzheimer’s disease begins to develop long before any symptoms become noticeable, but it’s very difficult to detect such changes,” said co-first author Andrea Castegnaro, PhD student in UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and UCL Electronic & Electrical Engineering.

“Virtual reality tests could be a valuable way to identify Alzheimer’s early on, and provides a powerful tool for investigating cognition,” said Professor Neil Burgess, Director of the UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience.

In 2014, Professor John O’Keefe (UCL Cell & Developmental Biology, Director of the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre) was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for ‘discoveries of cells that constitute a positioning system in the brain’. Essentially, this means that the brain contains a mental ‘satnav’ of where we are, where we have been, and how to find our way around.

A key component of this internal satnav is a region of the brain known as the entorhinal cortex. This is one of the first regions to be damaged in Alzheimer’s disease, which may explain why ‘getting lost’ is one of the first symptoms of the disease. However, the pen-and-paper cognitive tests used in clinic to diagnose the condition are unable to test for navigation difficulties.

A team of researchers at UCL and Cambridge have now developed and trialled a VR navigation test in patients at risk of developing dementia.

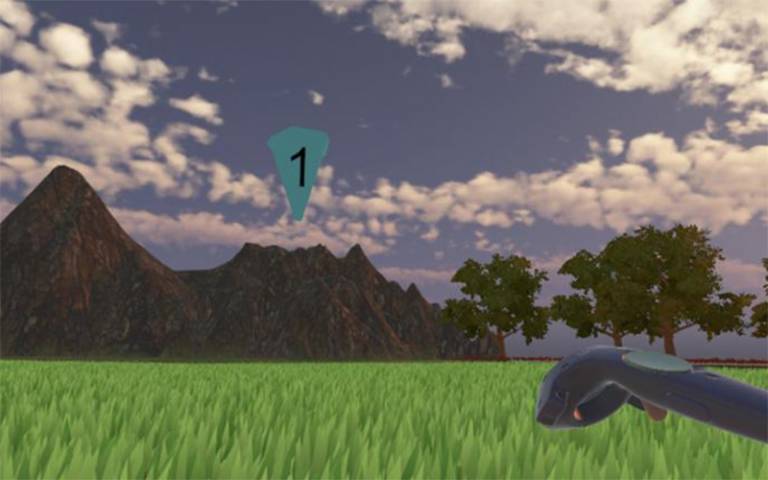

In the test, a patient dons a VR headset and undertakes a test of navigation while walking within a simulated environment. Successful completion of the task requires intact functioning of the entorhinal cortex, so the team hypothesised that patients with early Alzheimer’s disease would be disproportionately affected on the test.

The team recruited 45 patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) from the Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust Mild Cognitive Impairment and Memory Clinics. Patients with MCI typically exhibit memory impairment, but while MCI can indicate early Alzheimer’s, it can also be caused by other conditions such as anxiety and even normal aging. As such, establishing the cause of MCI is crucial for determining whether affected individuals are at risk of developing dementia in the future.

The researchers took samples of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to look for biomarkers of underlying Alzheimer’s disease in their MCI patients, with 12 testing positive. The researchers also recruited 41 age-matched healthy controls for comparison.

All of the patients with MCI performed worse on the navigation task than the healthy controls. However, the study yielded two crucial additional observations. First, MCI patients with positive CSF markers – indicating the presence of Alzheimer’s disease, thus placing them at risk of developing dementia – performed worse than those with negative CSF markers at low risk of future dementia.

Secondly, the VR navigation task was better at differentiating between these low and high risk MCI patients than a battery of currently-used tests considered to be gold standard for the diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s.

“These results suggest a VR test of navigation may be better at identifying early Alzheimer’s disease than tests we use at present in clinic and in research studies,” said the study’s lead author Dr Dennis Chan (University of Cambridge), who previously completely a PhD in Professor O’Keefe’s lab.

VR could also help clinical trials of future drugs aimed at slowing down, or even halting, progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Lack of comparability of memory tests between animal models and human participants represents a major problem for current clinical trials.

“The brain cells underpinning navigation are similar in rodents and humans, so testing navigation may allow us to overcome this roadblock in Alzheimer’s drug trials and help translate basic science discoveries into clinical use,” said Dr Chan.

The VR research was funded by the Medical Research Council and the Cambridge NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. The app-based research is funded by the Wellcome, the European Research Council and the Alan Turing Institute.

The study also involved researchers in UCL Psychology & Language Sciences and the UCL Institute of Communications and Connected Systems

Links

- Research paper in Brain

- UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience

- UCL Electronic & Electrical Engineering

Image

Example environment from the virtual reality display. Credit: University of Cambridge

Source

Media contact

Chris Lane

tel: +44 20 7679 9222

E: chris.lane [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close