People's motivations bias how they gather information

28 June 2019

People are prone to jumping to conclusions when the evidence seems to support what they want to believe, finds a new UCL study.

By fitting people's behaviour to a mathematical model, the researchers identified why people stop looking for new information more quickly when the early evidence fits their desired answer, reported in their new PLOS Computational Biology paper.

"Our research suggests that people start with an assumption that their favoured conclusion is more likely true and weight each piece of evidence supporting it more than evidence opposing it,” said the study’s lead author, PhD candidate Filip Gesiarz (UCL Psychology & Language Sciences).

“Because of that, people will find no need to gather additional information that could have revealed their conclusion to be false. They will stop the investigation as soon as the jury tilts in their favour."

Previous studies had already provided some clues that people gather less information before reaching desirable beliefs. For example, people are more likely to seek a second medical opinion when the first diagnosis is grave. However, certain design limitations of those studies prevented a definitive conclusion and the reasons behind this bias was previously unknown.

In this new study, 84 volunteers played an online categorisation game in which they could gather as much evidence as they wanted to help them make judgements and were paid according to how accurate they were. In addition, if the evidence pointed to a certain category they would get bonus points and if it pointed to another category they would lose points.

While there was reason to wish the evidence pointed to a specific judgement, the only way for volunteers to maximize rewards was to provide accurate responses. Despite this, they found that the volunteers stopped gathering data earlier when it supported the conclusion they wished was true than when it supported the undesirable conclusion.

"Today, a limitless amount of information is available at the click of a mouse," said senior author Professor Tali Sharot (UCL Psychology & Language Sciences).

"However, because people are likely to conduct less through searches when the first few hits provide desirable information, this wealth of data will not necessarily translate to more accurate beliefs."

Next, the authors hope to determine what factors make certain individuals more likely to have a bias in how they gather information than others. For instance, they are curious whether children might show the same bias revealed in this study, or whether people with depression, which is associated with motivation problems, have different data-gathering patterns.

The study was funded by Wellcome.

Links

- Research paper in PLOS Computational Biology

- Professor Tali Sharot's academic profile

- Affective Brain Lab

- UCL Psychology & Language Sciences

Source

- PLOS Computational Biology

Image

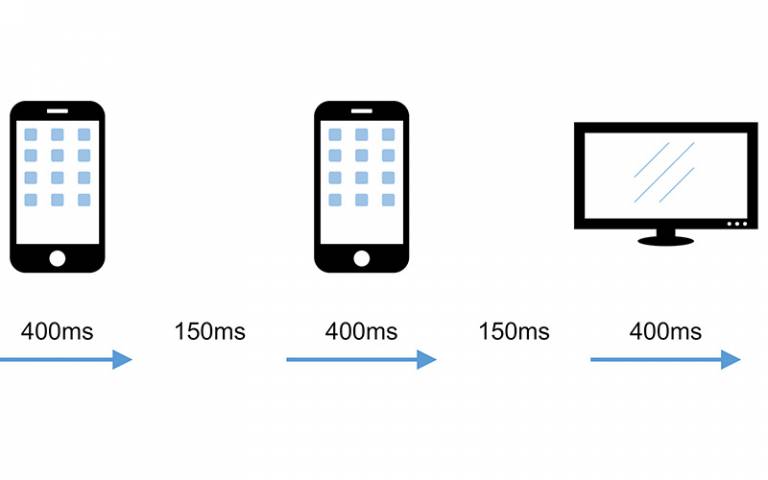

- Graphic of task from the study. On each trial participants saw TVs and phones moving along the screen and had to guess if they were in a TV factory (that sometimes produces telephones) or a phone factory (that sometimes produces TVs).

Media contact

Chris Lane

tel: +44 20 7679 9222

E: chris.lane [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close