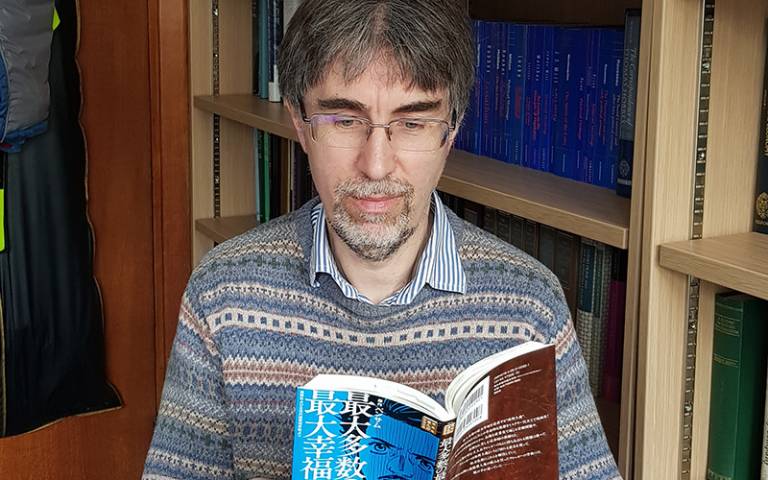

Spotlight on Professor Philip Schofield

10 April 2019

Professor Schofield is Director of the Bentham Project and General Editor of the new edition of The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham, as well as Professor of the History of Legal and Political Thought in the Faculty of Laws.

What is your role and what does it involve?

I am Director of the Bentham Project and General Editor of the new edition of The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham as well as Professor of the History of Legal and Political Thought in the Faculty of Laws. The Bentham Project was established in 1959 in order to produce a new edition of Bentham’s works that would form an authoritative basis for scholarship. I am the fourth General Editor, and given that we are not yet half way through, there will probably be several more. Volume 34 out of a projected 80 volumes in the edition was published a few days ago. The bulk of Bentham’s manuscripts, around 85,000 pages (there are another 15,000 in the British Library) were given to UCL by John Bowring, Bentham’s literary executor, in the 1840s. Most of the material has either never been published or only published in an unsatisfactory and misleading form. Hence my main job is to manage the publication of the new edition. I’ve edited or co-edited eleven volumes in the series and overseen the publication of five or six more. Every volume brings different challenges both from the point of view of textual editing and subject-matter.

The Bentham Project is at the centre of an international web of scholarship and world-renowned for its production of the new edition. There is nothing comparable in size and importance except the Marx-Engels edition based in Berlin. Having said that, isn’t Bentham more important than Marx?

How long have you been at UCL and what was your previous role?

I first came to UCL in September 1980 as a PhD student, left in September 1983 in order to undertake a teacher training course at what was then called the Polytechnic of Manchester, but returned to UCL on Monday 1 October 1984 in order to take up a one-year post as a Research Assistant at the Bentham Project. (Easter Sunday fell on 22 April in 1984, and that won’t happen again until 2057). Thirty-four-and-a-half years later, and UCL still hasn’t managed to get rid of me. I suppose that means that my previous role, as long ago as the summer of 1977, was working as a temporary warehouseman in a temporary warehouse for a textile firm—in those days there was still a textile industry in Lancashire. I remember it well because my fellow worker (a friend of mine who the firm hired on my recommendation!) offered to make the tea but only on condition that I gave up sugar. I haven’t had sugar in my tea since. Summer jobs more or less disappeared at the end of the 1970s, and so I didn’t have any gainful employment until I started work at UCL.

What working achievement or initiative are you most proud of?

Maintaining the Bentham Project through managing to obtain a series of external grants. I’ve received funding from the AHRC, ESRC, Leverhulme Trust, Mellon Foundation, Wellcome Trust, and European Research Council, often more than once, over the years. The Bentham Project’s core mission is to produce volumes in the Collected Works, but I’ve been really pleased to oversee Transcribe Bentham, our prize-winning scholarly crowdsourcing initiative. Established in 2010, it’s probably one of the UK’s longest running Digital Humanities projects. Volunteers have transcribed and encoded well over 20,000 pages of Bentham’s manuscripts—there are about 100,000 altogether, and with transcripts produced over the years by Bentham Project staff, we have now transcribed nearly half of them. As part of Transcribe Bentham we have been involved in a major European project to develop Handwritten Text Recognition. By training computers to read historical handwriting, we have been involved in a project that could (and should) transform research in the arts and humanities.

The problem is that we run into periodic funding crises, which mean that staff always face uncertain futures. UK academia does not address the problem of how to maintain long-term research projects in the arts and humanities. My priority now is to get funding both to keep Transcribe Bentham up and running and maintain progress on the edition.

Tell us about a project you are working on now which is top of your to-do list

My colleague Tim Causer and I are completing Bentham’s writings on Australia, and a substantial volume will go to the press by the end of the year. Bentham thought that convicted criminals shuld be housed in his proposed panopticon prison, which would reform them and deter future potential criminals, rather than send them on a hazardous voyage to New South Wales, which would not achieve any of the legitimate ends of punishment. On 11 and 12 April we will be hosting a conference here at UCL, with leading historians of Australia and of the British Empire more generally, who will discuss Bentham’s ideas and historical influence on the course of Australian history.

What is your favourite album, film and novel?

The album I probably listen to most often at the moment is ‘Transformer’ by Lou Reed. It was recorded in London in 1972, contains witty lyrics, some great songs (including ‘Perfect Day’ and ‘Walk on the Wild Side’), Mick Ronson on guitar, and David Bowie on backing vocals. I suppose I was always attracted to ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ because walking on the wild side is something I would never have been likely to do! If not ‘Transformer’, then I would say the unfairly maligned ‘Tales from Topographic Oceans’ by Yes. This double album contains four songs each of about twenty minutes’ duration. The musicianship is superb and the tunes catchy—just don’t worry too much about the lyrics.

My favourite novel is ‘Lord of the Rings’—I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve read it. My favourite film should, therefore, be Peter Jackson’s ‘Lord of the Rings’, but I reckon that, given he managed to drag out ‘The Hobbit’ into three films, he might have made ‘Lord of the Rings’ into nine, especially in the light of the success of the almost interminable ‘Game of Thrones’. The issues I have with Jackson’s ‘Lord of the Rings are that (1) he completely misses out Tom Bombadil and (2) the scouring of the Shire, (3) confuses the chronology, which is so carefully worked out by Tolkien, (4) ignores the Numenoreans, (5) brings the Army of the Dead to the Pelennor Fields, (6) swaps Elrond’s sons for Arwen, etc. etc. etc. They are still great films, but why not be as faithful of possible to the book? Surely a fictitious film should be as close a representation of a fictitious book as possible?

What is your favourite joke (pre-watershed)?

The philosopher Descartes was on an aeroplane going from Amsterdam to Stockholm. The flight attendant asked him whether he would care for a glass of red wine. He responded ‘I think not’ and promptly disappeared.

If you don’t think that is funny, then you might like this: Q. What did the policeman say to the criminal’s belly button? A. You’re under a vest.

Who would be your dream dinner guests?

I would invite Jeremy Bentham if he were alive, but he probably wouldn’t come. He refused to dine away from home for about the last 20 years of his life. I suppose I could have his auto-icon, but that might put off any one else from coming. Having said that, being invited to dinner would not be a novelty for the auto-icon. The auto-icon was created by Bentham’s surgeon Thomas Southwood Smith, who kept it at his home as an ‘attraction’, where it sat at his dinner table. When in 1850 Smith moved to a smaller house and decided he no longer had room for his non-paying guest, the auto-icon took up residence at UCL.

What advice would you give your younger self?

Go round the second-hand record shops and buy up as many LPs on the Vertigo Swirl label as possible. There were about 90 records issued on this label in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and original copies of most of them are now sold for several hundreds of pounds each. I wouldn’t sell them – I would just like to have them in my vinyl collection.

What would it surprise people to know about you?

I have a compulsion to go into charity shops and look for jigsaws, of at least 500 and preferably of 1,000 pieces, which have trains for their subject-matter. Having assembled these jigsaws (usually during Bank Holiday weekends), I put them into the recycling bin if they have any pieces missing, but if they are complete, I give them back to the charity shop. I am, therefore, doing my bit towards purging the world of incomplete train jigsaws. Is there anything surprising about that?

What is your favourite place?

The Bentham Project, of course. If that answer is not regarded as credible, then my own back garden on a Bank Holiday (doing a train jigsaw, of course); and if that answer is not regarded as credible, then Ambleside in the Lake District. Studying Bentham has taken me to all sorts of interesting and wonderful places around the world, but I haven’t been anywhere I like to go so much as the Lakes. This may just be due to the fact that we had family holidays there until I was about ten years old, always going to Mrs Booth’s farm in Burneside near Kendal. Having said that, I do have a painful memory of Mrs Booth’s farm. There was no television for the guests, and so I missed seeing the 1966 World Cup Final. Now that is a sad note on which to end.

Close

Close