Phantom limb pain origins identified in brain stimulation therapy advance

14 December 2018

Scientists studying phantom limb pain believe they may have found the part of the brain that can enable pain relief in people who have lost a limb, according to a new UCL, Oxford University and ETH Zürich study.

The study, published in Annals of Neurology, identified brain areas that predicted pain relief after brain stimulation treatment, suggesting that those areas have a driving role in phantom limb pain and may be new areas to target in clinical trials.

“People who experience phantom limb pain have been waiting a long time for reliably effective treatment options. We believe that incomplete success of phantom pain treatment is due to our partial understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying this curious phenomenon,” said Dr Tamar Makin (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience), the study’s senior author.

“We’re hopeful that the early success of the treatment we used and the new insights we’ve gained could help lead to much-needed pain relief for many people.”

Phantom limb pain is commonly experienced by people after an amputation, as a recurring feeling of pain coming from the missing limb.

For the study, 15 amputees who experienced frequent phantom limb pain were given non-invasive brain stimulation therapy – delivering a mild current through the brain via electrodes – while performing simple phantom hand movements (focusing on moving the hand that has been amputated).

The current was directed towards the ‘missing hand cortex’ of the sensorimotor area of the brain, which has previously been associated with phantom limb pain. The current affected a larger area of the brain than just the target region.

The participants were given the therapy while in an MRI scanner, so the researchers were able to track brain activity throughout the treatment.

A single 20-minute session of brain stimulation therapy reduced phantom limb pain to a clinically relevant degree, with effects lasting at least a week.

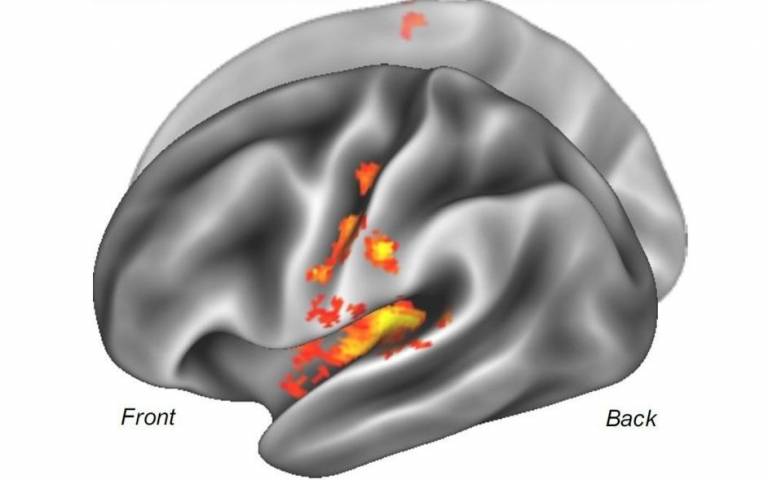

The researchers found that the degree of pain relief was associated with reduced activity in the missing hand cortex after the treatment, as expected. Importantly, this was preceded by increased activity in pain-related brain areas, such as the insula and secondary somatosensory cortex, during the treatment itself.

The researchers speculate that doing the phantom hand movement task during the treatment may have driven current to those areas, which are involved in pain, touch and movement, and may explain the success of the treatment, but they say that further research is needed.

The researchers say their findings suggest the missing hand cortex is not the driving cause of the pain; rather, the heightened activity found in that area may be a consequence rather than a cause of the pain.

“It’s still unclear why people experience phantom limb pain, but one of the possible reasons is that the nerves sending signals from the hand to the brain remain partly active, sending signals to the brain that are problematic and interpreted as painful. Our findings support that theory by suggesting the importance of doing phantom limb movements in conjunction with brain stimulation therapy,” said the study’s lead author, Dr Sanne Kikkert, who began the study at the University of Oxford before moving to ETH Zürich.

“I know a lot of people have very bad phantom limb pains: for some it feels like their arm is going through a grinder. I used to feel a very sharp stabbing phantom limb pain, as if somebody was stabbing a needle into my arm. This pain reduced dramatically quite quickly after I did the treatment. I didn’t wake up anymore due to intense pains in the night and I noticed the pain went from a 30 to a one or two,” said Chris, one of the participants in the study.

“We’re hopeful that the pain relief experienced by the participants in this study will be replicated in larger studies, but caution that more research is needed to understand the disease mechanism and for clinical trials to see how well this treatment could work. Phantom limb pain is notoriously difficult to treat. Interestingly, in this group of 15 patients, our brain stimulation treatment stood out well compared to other treatments options,” said Dr David Henderson-Slater (Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust), the lead clinician for the research.

The study was funded by Wellcome, the Royal Society and the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.

Links

- Research paper in Annals of Neurology

- Dr Tamar Makin's academic profile

- UCL Insitute of Cognitive Neuroscience

Image

- Brain areas with heightened activity during treatment that correlated with pain relief (Credit: Dr Sanne Kikkert)

Media contact

Chris Lane

Tel: +44 (0)20 7679 9222

Email: chris.lane [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close