Four ways to live a happier life: lessons from computational neuroscience

18 July 2017

If you've ever searched your local WHSmith for a comprehensive guide on how to be a happy bunny, then you've just clicked on the right article.

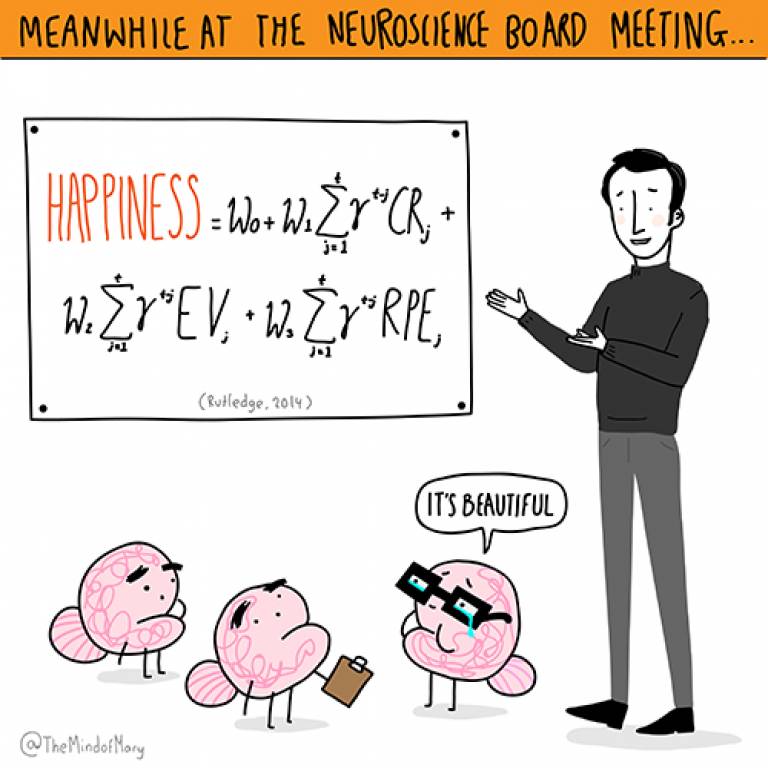

In 2014, Dr Robb Rutledge, a cognitive

and computational neuroscientist based at the Max Planck UCL Centre for

Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research (*and breathe*), published a Happiness

Equation. Yes, really. (You can read about it here for free).

In 2014, Dr Robb Rutledge, a cognitive

and computational neuroscientist based at the Max Planck UCL Centre for

Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research (*and breathe*), published a Happiness

Equation. Yes, really. (You can read about it here for free).

But for those of us

who aren't terribly mathematically fluent, what does it actually mean? How can

we, as mere mortals, ever achieve true happiness?

Well, look no further: here are four lessons that might help us all to live a happier life, based on scientific findings kindly shared with us by the one and only Dr Rutledge himself.

1. Make errors faster

Making mistakes can be

a scary thing to do; what's more, making them on purpose can seem a little

contradictory. However, Dr Rutledge explains that our failures can tell you

just as much about a situation as our successes can. Nonetheless, be sure to

not spend all your time blindly making errors, pick your mistakes wisely.

Some mistakes will be more useful to make than others will. Identify situations where you can learn useful things that help you to get towards your goals. After all, time is precious in academia (and in life, young grasshopper).

2. Know that happiness indicates meaningfulness

A lot of us (myself

once included) believe that, in order to be happy, you must live a life that is

saturated by an unrealistically large number of consecutively occurring happy

events. However, this isn't quite the case.

According to Dr Rutledge, happiness is simply an indicator of whether recent events bring us the things we care about in life. For example, doing a degree, marrying the person you love, or even spending quality time with your cat, Mr. Fluffles, might bring you happiness. The things that consistently increase your happiness are those that give your life meaning.

3. Be mindful of sadness too

Loads of things make us sad on a daily basis. Having arguments with people you care about, being ill or overworked on your PhD project, or rewatching the end of La La Land for the 25th time this week whilst crying over an empty ice cream bucket, to name just a few. But here's the thing: being sad isn't quite as terrible as you might think it is.

According to Dr Rutledge, the feeling of being unhappy can tell you that your environment is getting worse. That's a useful thing to be aware of that might guide you to change your next move. For example, if being alone in the lab/library whilst working on your research project makes you feel like crying an ocean of tears at the end of each day, this could be an indicator of unnecessary isolation. To fix this, you might change your work environment, or join a society, attend a gym class, or even go out with friends for lunch more often.

4. Always have realistic expectations

In his Happiness

Equation, Dr Rutledge finds that happiness depends not on how well we are

doing, but whether we are doing better than expected. Happiness also increases

when we have positive expectations about a future event.

Dr Rutledge suggests

that in general having realistic expectations is best, because we rely on those

expectations to make good decisions. Before something didn't turn out the way

you wanted it to, what exactly did you anticipate happening?

To make it easier to accept the 0.00005% success rate* that life more-than-often tends to offer, you'd want your expectations to be as accurate as possible. To do this, you could ask around: what has been the experience of others who've done what you're attempting to do? Do you have the fully developed skill set that is needed to do it or would you need to work on it some more? Have you given yourself enough time or number of attempts to do the thing?

Eventually, you'll find that life is rarely ever quite as straightforward as you may want it to be - and that is okay too. Just remember to stick to reasonable expectations and never give up on the things that are important to you or bring meaning to your life. Happiness is a tangible state of mind; especially when things turn out better than expected.

*author's own very unscientific estimate.

To find out more about the brilliant research and findings of Robb Rutledge and his talented group, you can visit his lab's website at www.RutledgeLab.org or follow him on Twitter at @RobbRutledge

Maryam Clark, myUCL Student Journalist

Maryam Clark is a Biosciences PhD student at the UCL School of Life and Medical Sciences and is a student journalist for myUCL.

Close

Close