Provost's View: Unveiling the mysteries of university finance

11 June 2015

Over the last few weeks, we have been working on UCL's budget for next year.

It will go to Council for approval in July, in time for

the start of the 2015/16 financial year on 1 August.

It will go to Council for approval in July, in time for

the start of the 2015/16 financial year on 1 August.

With that in mind, I thought it might be helpful to devote my column this week to explaining why keeping the institution in good financial shape is both essential and challenging, and how we are all going to need to engage with this agenda to ensure that we have the funds necessary to invest in ensuring UCL's continued success.

Sector context - static funding and starved infrastructure

First, let's look at the context. It would take a very brave person to argue that managing university finances is going to get easier in the next few years. Research funding is likely to be static nationally in cash terms, with inflation eating away at its real value. We may continue to increase our share of that funding, as we have been doing with considerable success in recent years, but this process will most likely slow down at some point.

Research funders are, in general, reluctant to pay the full cost of the activity they fund, so research tends to be 'money in and money out' with little or nothing left over for investment in infrastructure or new activity. The REF had a very positive effect on our global research reputation and it also brought in some welcome additional income, at £6.7m a year. However, given the investment we made pre-REF in new posts, it would be fair to say that we were hoping for a better overall financial outcome.

Outstanding research is central to the mission of UCL and is one of the key reasons that we have a global reputation and attract the best students and staff, but it does not pay the bills on its own.

With regard to teaching, the shift from government grants to fees has had a dramatic impact on university finances. The home undergraduate maximum fee of £9k is reduced in effect by the requirement to spend about £2k per head on bursaries for students and widening participation - something we all support, but nonetheless an important factor in UCL's finances. What is more, the £9k fee has been capped since its introduction in 2012, and over that time its real value has already declined significantly. It remains to be seen whether the new government has a change to indexation of the £9k fee on its list of priorities. Fees for postgraduate taught and international students are unregulated, and over recent years UCL has tried to take a more realistic view, when setting fees, of the cost of delivering an excellent student experience in London.

UCL context - academic excellence with infrastructure needs

Historically, UCL's academic performance has been outstanding, but our financial performance has not kept pace. If we go back before 2009/10, UCL simply aimed to cover its costs each year, so annual expenditure matched annual income. The effect of this is clear for all of us to see, in terms of insufficient funds for investment and thus creaking infrastructure and relatively poor-quality facilities. Long-term maintenance has suffered, equipment has not always been updated, and we have not kept our infrastructure developments sufficiently aligned with our significant growth in student and staff numbers, nor with the growing expectations of our students and staff. As a result, many of our buildings have deteriorated and some have become unfit for purpose.

You might think that in a tight funding environment, it would be impossible to generate funds for future investment without compromising academic excellence, but the evidence suggests otherwise.

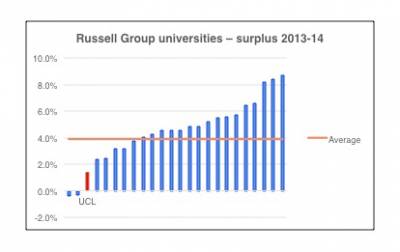

As this chart shows, our research intensive peers have achieved a better financial performance than UCL, which demonstrates that excellent academic performance can be delivered alongside budgetary prudence.

Moreover, sector-wide data show that UCL is in the lower quartile for financial performance and this is something that we need to address now to avoid problems in the future.

Shaping up for a strong financial future

So, how do we ensure that we have the resources to deliver sustainable academic excellence? The first task has been to define our financial objectives. As a not-for-profit charity, UCL's overriding objective must be not only to cover its operating costs, but also to generate resources for investment, so that over time buildings and infrastructure are renewed and we have funds for investment in new initiatives, so that our intellectual assets are renewed as well. That's how we define financial sustainability alongside academic excellence. Looking at our financial performance and that of our peers, we have concluded that a surplus of 5.5% of income is achievable, and will generate - just - enough funds for the investments we need to make.

The biggest call for investment is the estate, as nobody will be surprised to hear, and over the next ten years we plan to spend £1.25bn, or an average of £125m a year, the vast majority of which will be spent in and around Bloomsbury. Given the relatively poor condition of our estate and the need for space, a difficult process of prioritisation of spend has been necessary, and we have had to defer several projects that would have been desirable.

It is often said that capital spend is about shiny new buildings. In UCL's case, it is in fact mostly about refurbishing existing space, and while I am sure the results will be of good quality, we are certainly not being extravagant in our approach. I believe that such a level of investment in our estate and other infrastructure is essential if we are to provide our staff and students with the modern facilities that they need and deliver our UCL 2034 strategy.

There will be two major new builds during this period, the New Student Centre and UCL East. The New Student Centre will meet our desperate need for new space for students to study on campus, and provide a range of other services. UCL East will cost us up to £287m, but less than that if we succeed in attracting philanthropic income and funding from collaborators. At most, it represents less than 25% of the total capital programme and it is our only opportunity to provide significant space for new activity, and at a dramatically lower cost than in Bloomsbury.

The financial strategy is designed to get us from the 2% surplus we have been achieving since 2009, to 5.5% by staged annual increases. This degree of improvement will be challenging but achievable without major disruption. In order for the surplus to increase, we have to increase our income and/or reduce costs. Based on the success of UCL, one of the very natural responses has been to seek growth in order to generate additional income, for example through new teaching programmes. This is an important part of the strategy and in some areas of UCL there were good academic reasons for seeking growth.

Post-REF, however, we need to look very hard at cases for further growth in staff and student numbers. There are other obvious constraints too, in that new degree programmes tend to drive new demands for space and other facilities, and unless we plan carefully we run the risk that additional costs erode the benefit of additional income, or that the demand for new facilities outstrips our ability to deliver them.

For 2015/16, the surplus target increases to 3.5%. Given the limitations on growth, we have been working on plans to make sure that we can achieve the target. We have modelled the effect of measures we can take and, on a realistic assessment, they will, between them, deliver enough to achieve the surplus.

How UCL can achieve the necessary surplus?

The 'big ticket' items are: postgraduate taught and international fees, the balance between international and home student numbers, and a somewhat greater degree of care over academic and support costs, particularly in considering the establishment of new posts. I believe that the goals we have set are both essential to the continued success of UCL and achievable. If we are going to succeed we will need your support and engagement, and I trust I can count on that. My office is setting up meetings with faculties so that I can discuss the issues directly with deans and their heads of department, vice-deans and key professional services staff.

Finally, I recognise that there are some challenging financial messages here, but it is essential that we all understand the importance of improving our financial performance. My motivation for getting this right is really quite simple; UCL is one of the world's leading research-intensive universities and I intend to ensure during my time as President & Provost that it not only stays in that elite group, but also gains even greater prominence, as outlined in UCL 2034. We will only achieve that if we are financially secure.

I will provide an update on this important issue in the autumn. In the interim, I would also suggest that you take a look at some newly prepared frequently asked questions (FAQs) about UCL's finances.

Professor Michael Arthur, UCL President & Provost

Links:

Close

Close