Frequently asked questions about university finances

11 June 2015

Why does UCL need to make a surplus? What happens to the surplus each year? Don't we have a strong balance sheet? What do we mean by 'financial sustainability'? What do we mean when we talk about the 'full economic cost' of an academic activity? How have we arrived at a capital plan of £1.

25bn

over the next ten years?

25bn

over the next ten years?

1) Why does UCL need to make a surplus?

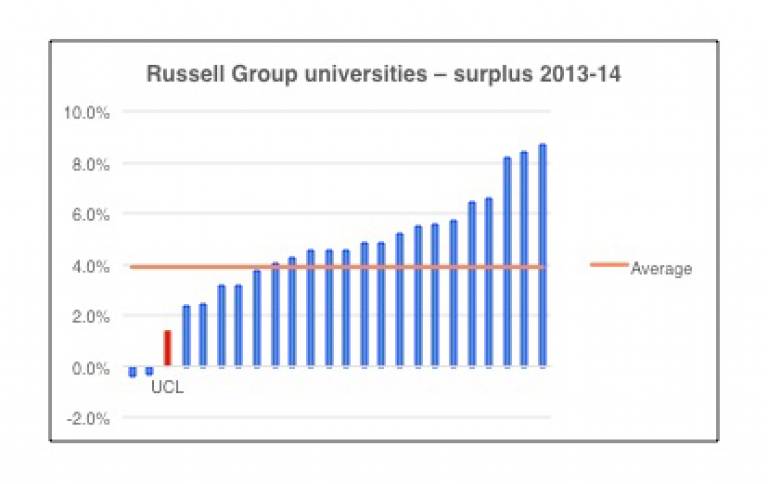

UCL is a charity and therefore only needs to make a surplus in order to generate funds for re-investment in the organisation, and for meeting unforeseen adverse circumstances, such as large one-off unexpected costs. Investment is planned to support delivery of UCL 2034, including new academic developments, improving the quality of buildings and facilities, and enhancing our information technology. Without surpluses we will not have the funds to make that investment. Our performance in generating an annual surplus has been at the lower end compared to other research-intensive universities (see Table 1: Russell Group universities - surplus 2013-2014).

2) What happens to the surplus each year?

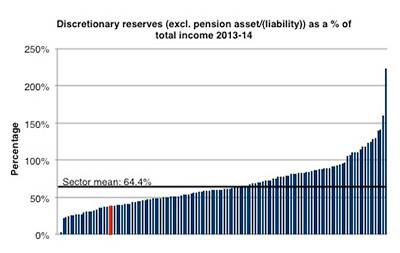

At the end of each year, the surplus is added to our reserves. The reserves are then used to fund investment that cannot be met from our normal recurrent sources of revenue. Our weaker performance in generating surpluses has left us with a below average level of reserves (see Table 2: Discretionary reserves as a % of total income 2013-2014).

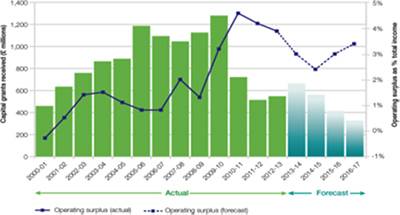

In the past, we could rely on government capital grants to support expenditure on buildings and facilities. These grants have reduced dramatically in recent years and often require matched funding from UCL (see Table 3: Capital grants received).

3) Don't we have a strong balance sheet?

We do, and that strength will help make us a highly attractive proposition for those lending us money and supporting us via philanthropy. Because accounting convention uses historic costs, the value of the property we own and occupy is many times greater than its value as recorded on our balance sheet. We offer a high-calibre, long-term secure option for investors and we will take full advantage of that.

4) What do we mean by 'financial sustainability'?

A standard definition is "being able to continue to generate surpluses and to invest over the long term to deliver the mission of the institution". For UCL, this translates into a position whereby we not only cover our operating costs, but also generate resources for investment, so that over time, buildings and infrastructure are renewed and we have funds for investment in new initiatives, so that our intellectual assets are renewed as well.

5) What do we mean when we talk about the 'full economic cost' of an academic activity?

Academic activity incurs direct costs - the pay costs of staff involved, and the materials and equipment utilised. Activity also gives rise to indirect costs - the utilisation of facilities shared across many activities, including shared research facilities, use of libraries, information technology, support functions such as Student and Registry Services and the estate that we occupy. The utilisation of these facilities and services incurs a cost both in their delivery and in providing for their replacement. The full economic cost of an activity is the sum of all those direct and indirect costs.

6) How have we arrived at a capital plan of £1.25bn over the next ten years?

Each faculty was asked to identify their priorities for the development of the estate. To this were added other priorities that relate to the development of shared UCL-wide facilities and which recognise the need for substantial upgrade of some existing buildings. These projects were assessed against a set of criteria, which included the delivery of UCL 2034, in order to determine an overall programme for the next 10 years that can be delivered within an envelope of £1.25bn. This sum was arrived at by determining the maximum sum we could afford, allowing for new borrowing, and ensuring we have sufficient cash for our day-to-day needs. It also represents the limit of our capacity to disrupt the estate with building works during this period.

7) Within the capital plan, how are projects prioritised and how are decisions made?

Each project can only proceed once a business case has been developed and authorised at the appropriate level. For the larger projects, this will be the UCL Council. The business case requires the articulation of a strong academic rationale and fit with UCL 2034. It also requires a detailed consideration of options, a financial evaluation and assessments of risk, environmental impact and proposed project governance.

8) What is the profile of spend on the capital plan for Bloomsbury vs UCL East?

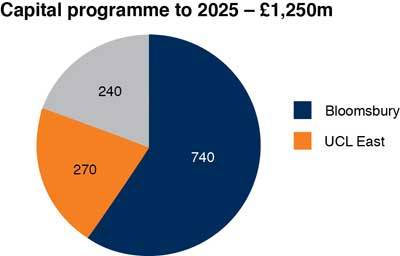

A proportion of the planned spend is neither Bloomsbury nor UCL East, since it also includes facilities co-located with hospital partners and other UCL premises beyond Bloomsbury. The analysis of spend in these categories is, broadly, £740m (59%) in and around Bloomsbury, £270m (22%) UCL East and £240m (19%) in other locations. It will deliver new and improved facilities for all faculties and departments (see Table 4: Capital programme to 2025 - £1,250m).

9) Why is UCL East so important to our future?

UCL East on Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park (QEOP) presents a unique opportunity to offer a new kind of university environment, focused on the facilitation of collaboration, connection and open innovation with local and global communities. UCL East will:

· be a home for new UCL activities, not simply an extension of our Bloomsbury functions

· serve as a model for the university campus of the future - open, dynamic and overcoming the conventional barriers between research, education, innovation, public engagement and collaboration

· provide an outstanding environment for learning and scholarship for students, staff, collaborators and the public

· liberate space and enable new opportunities in the Bloomsbury estate

· as a founder member of 'Olympicopolis', play a central role in the sustainable development of the QEOP and east London's innovative quarter more generally

· facilitate delivery of UCL 2034, the university's 20-year strategy.

10) What happens to the university's finances if we deliver the capital plan over 12 or 15 years, instead of the current 10-year plan?

Relaxing the timescale for delivery of the capital plan allows us to reduce the amount we need to borrow, eases the pressure a little on the need to increase our operating surplus and may alleviate the impact of disruption to parts of our campus that will be refurbished or redeveloped. The impact in terms of reducing our surplus requirement would not however be significant; between £4.6m and £8m by 2017-18. Such a delay would, however, defer the delivery of the benefits associated with this investment - enhanced student experience, additional capacity for academic innovation, improving the quality of research and teaching facilities, the ability to attract top academics from around the world, and so on. This would put in jeopardy delivery of UCL 2034 and require us to recalibrate our level of ambition.

11) Why can't we slow down the rate at which we are currently planning to increase our annual surplus?

The rate at which we need to increase our annual surplus and scale/pace of the capital plan are directly linked. The cash to pay for the capital programme is a combination of funds we generate from our operations (our surpluses, past and future), some additional borrowing and contributions from philanthropy and other third parties. The surplus to which we aspire, 5.5% of total income, is modest. It is already being achieved by a third of Russell Group universities and they are all, like us, aiming to increase their surplus to fund their plans for capital investment.

12) Why don't we just grow our income through growth of the institution to solve this financial problem?

Growth of activity is only viable if we can generate the income to recover the full economic cost of that activity, and therefore ensure we can re-invest in the facilities and services which that activity requires. It is also constrained by the level of demand and by our physical capacity to accommodate more activity. These are very real constraints and, while we can and will pursue viable opportunities for growth, we cannot rely on this as the means by which to improve our operating surplus. We will need to look at other approaches, including increasing the margin on existing activity by setting a price that more adequately reflects the full economic cost, and by examining opportunities for greater efficiency in our operations.

13) Why are our competitors doing better than us financially, and what can we learn from them?

Some are doing better because they have an inherently more financially viable operating model - less research intensive, lower proportion of charity-funded research, different profile of academic disciplines, non-London cost base, and so on. Others are doing better due, broadly, to two factors. Firstly, they begun some time ago the programme of capital investment that we are now embarking upon and are therefore already enjoying the benefits. Secondly, they have already attended to the need for greater financial discipline by, for example, eliminating duplication and inefficiency. We might argue that they have done so and not achieved the academic success that we have enjoyed. The trick is to do both!

14) How do our tuition fee prices compare to our competitors?

In the unregulated markets - postgraduate and overseas students - our fees are towards the upper end of the range, but below those of some of our competitors. The picture, inevitably, varies by discipline, but there are opportunities to increase our prices a little further without impacting upon demand or diluting our performance in access terms. The need to support tuition fees for more of our home/EU and international students through scholarships and bursaries is a key component of our philanthropic fundraising campaign.

15) Do we spend more on professional services than our competitors; either centrally or throughout the organisation?

The benchmarking we have undertaken indicates that we do not. That is, however, no basis for being complacent and we can all point to examples where we could be more efficient and improve the value we derive from these services. We have committed to a detailed benchmarking exercise to be undertaken this year with nine other Russell Group universities that will identify the comparative cost, activity by activity, and give us a more complete insight into where we can do better.

16) Why do my department and faculty contributions keep rising, but you always want more each year?

If we are to increase our surplus then contributions from all departments

and faculties must increase, in part to cover the full economic cost of the

expansion that has already occurred in our staff and student numbers pre-REF. The

contributions help generate the surplus but also pay for the services organised

at faculty, school and university level to support those activities. An

increase from 2.5% to 5.5% surplus in three years is equivalent to an extra £47m. Once

we achieve that level of performance (in 2017-18), and provided we can maintain

it, then the requirement for annual increases decreases markedly.

Read the full Provost's View: Unveiling the mysteries of university finance.

Close

Close