Vaccine for transplant infection shows promise

8 April 2011

A major infectious problem after organ transplantation, cytomegalovirus (CMV), could potentially be targeted with a vaccine, according to scientists from UCL and doctors at the Royal Free Hospital.

The results of this Phase II proof-of-concept study, published in The Lancet today, show that a vaccine preparation moderated the severity of CMV infection in patients waiting for kidney and liver transplants and, in some cases, may have interrupted transmission of the virus from donor to recipient.

CMV is part of the herpes family of viruses and is one of the most common viral infections. It is estimated that around 6 of every 10 adults in the UK have been infected by CMV, usually through contact with young children. It is typically unnoticed in healthy people because their lymphocytes keep the virus under control. However, the virus can be serious when it develops or reoccurs in certain vulnerable groups, particularly those with weakened immune systems such as organ transplant recipients, people with HIV and unborn babies.

CMV is sometimes referred to as the 'Toll of Transplantation' because of the high level of serious disease it can cause in this patient group - including pneumonia, lung complications and liver infection. Congenital CMV, when a woman becomes infected during pregnancy and passes the infection on to her unborn baby, can also have serious consequences. About 7 babies in every 1000 will be born with congenital CMV. More than 10 per cent of babies born with the virus will have symptoms at birth, such as learning difficulties and hearing loss. These same problems will develop in at least another 10 per cent of babies, even though they appeared to be normal at birth.

The study's lead author Professor Paul Griffiths, UCL Centre for Virology and Honorary Consultant at The Royal Free, said: "Many scientists thought that it would be impossible to make a vaccine against CMV because the virus works by evading the immune system, so they reasoned it would also evade a vaccine. However, this study shows that at least one vaccine preparation can moderate the severity of CMV infection, even in patients given immunosuppressive drugs and exposed to CMV in a transplanted organ. Although this trial just examines the vaccine in transplant patients, we expect that a vaccine could help other groups vulnerable to CMV such as pregnant women."

140 Royal Free patients awaiting transplantation of a kidney or of a liver were recruited to the trial. Half of these patients had had natural infection in the past, whereas half had never seen CMV before. After informed consent, they were randomised to receive the vaccine or a placebo. 78 of them proceeded to transplant and so had their CMV biomarkers measured following the operation.

All 67 patients given the vaccine responded by making antibodies against the CMV protein (glycoprotein B; gB) contained in the vaccine. The average quantity of antibodies made by the vaccine group was very significantly increased compared to the recipients of placebo. The level of these antibodies declined a little with time, but the vaccine recipients still had antibody levels which were significantly greater than the placebo recipients when they were called to transplant.

After transplant, the biomarkers of CMV were all reduced in those who had received the vaccine compared to recipients of placebo. The study was not designed to provide significant differences between these biomarkers in each of the four different subgroups of patients. However, the reduction in biomarkers was statistically significant in the patients in the highest risk category (recipients who had never seen CMV in the past who received organs from patients infected with CMV). In five such high risk cases, the study results show that the vaccine may have interrupted transmission of virus from donor to recipient, because their biomarkers remained undetectable at all times after transplant.

Professor Griffiths continued: "Based on these results, we conclude that it could be possible to make a vaccine against CMV that is able to protect against this important pathogen for transplant patients, as well as women of childbearing age whose unborn babies can be damaged by CMV. We hope these results will encourage multiple pharmaceutical companies to accelerate development of their CMV vaccine candidates for both groups of patients."

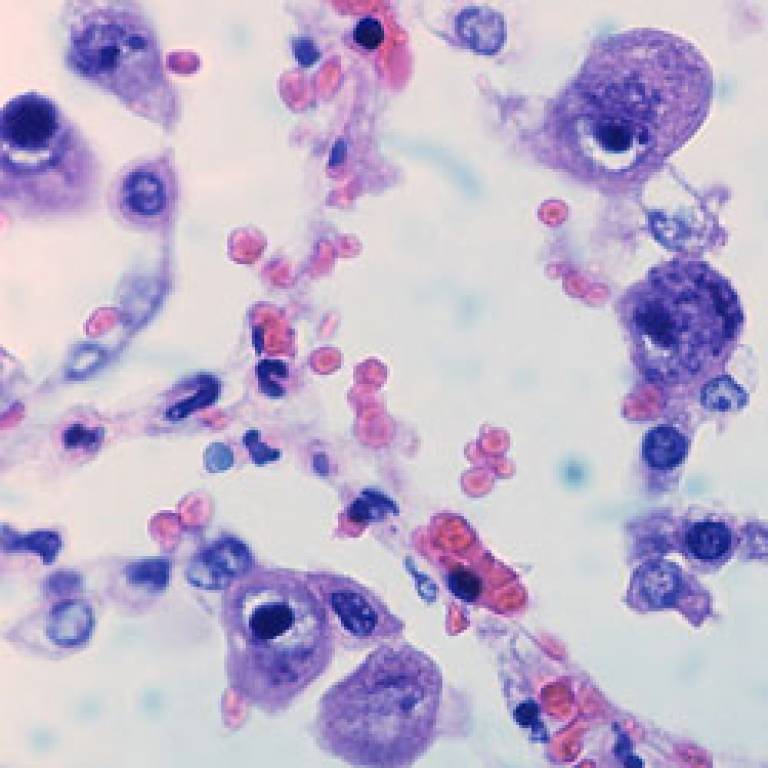

Image: Cytomegalovirus infection.

UCL context

UCL, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, the Royal Free Hampstead NHS Trust and UCL Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH) together make up UCL Partners, designated one of the UK's first academic health science centres by the Department of Health in March 2009.

UCL Partners brings together the combined skill and expertise of its clinicians and researchers to focus on child health, eyes and vision, immunology and transplantation, infectious diseases, neurological disorders, women's health, cardiovascular research and cancer.

Close

Close