UCL study: genes influence economic decision-making

5 May 2009

Links:

icn.ucl.ac.uk/Staff-Lists/MemberDetails.php?Title=Dr&FirstName=Jonathan&LastName=Roiser" target="_self">Dr Jonathan Roiser

icn.ucl.ac.uk/Staff-Lists/MemberDetails.php?Title=Dr&FirstName=Jonathan&LastName=Roiser" target="_self">Dr Jonathan RoiserUCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience

A team led by Dr Jonathan Roiser (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience) has today published research which shows that our genes affect the decisions we make, and that these decisions are influenced by the positive or negative framing of the options on offer.

This phenomenon is known as the 'framing effect'. For example, how would patients respond if they were told they had an 80% chance of surviving an operation? How many would consent if told that they had a 20% chance of dying?

Research published in the current issue of the Journal of Neuroscience shows that the extent to which individuals are influenced by framing may partly depend on their genetic make-up, as is the response of the amygdala, an area of the brain involved in processing emotions, which becomes active during decisions influenced by the framing effect.

Dr Roiser commented: "We know that people from across a variety of cultures are susceptible to biases when making decisions, and that even with training these biases are hard to overcome. This implies that hard-wired genetic influences might play an important role in determining how susceptible different individuals are to the framing effect."

In the study, Dr Roiser and colleagues showed that decision-making is affected by variation in the serotonin transporter gene, which several previous studies have noted also influences the response of the amygdala. The gene codes for a protein involved in the recycling of serotonin, a neurotransmitter essential for communication between nerve cells.

The researchers investigated two common variants of this gene, known as the 'short' and 'long' versions. The researchers selected thirty healthy volunteers carrying either a pair of short variants or a pair of long variants.

Participants in the study performed a task involving deciding whether or not to gamble with £50. They had to make the same decision twice; first through the 'gain frame' and then the 'loss frame'.

In the 'gain frame', option A was to keep £20 for sure and option B was to gamble, with a 40% chance of keeping the full £50 and a 60% chance of losing everything.

In the 'loss frame', option A was to lose £30 for sure and option B was the same gamble as above.

Despite the identical nature of the decision in the gain and loss frames - which all of the volunteers realised - the study showed that both groups of participants were more likely to gamble if the first option (option A) was phrased in terms of losing rather than keeping money.

Critically, those participants with two copies of the short variant were considerably more susceptible to the framing effect. "This doesn't mean that people with the short variants are risk takers," Dr Roiser explained. "In fact, they were risk averse in the 'gain frame' whilst risk seeking in the 'loss frame', which implies inconsistency in their decision-making."

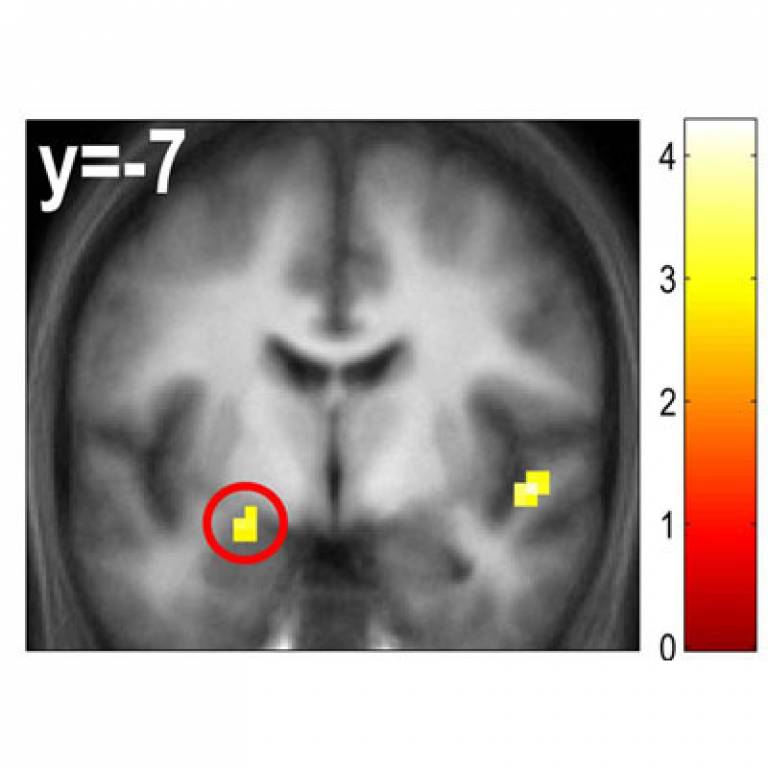

Brain images were taken while participants made their decisions, revealing a mechanism underlying this difference in decision-making behaviour. Participants with two copies of the short genetic variant had greater amygdala responses than their counterparts when making decisions influenced by the frame effect.

The researchers also measured the degree of interaction, or connectivity, between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, the brain region most implicated in human intelligence, personality and decision-making. When resisting the frame effect, the participants with two copies of the long variant had stronger connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, while those with a pair of short variants did not.

Dr Roiser added: "This difference in connectivity is really interesting. It suggests that the volunteers carrying the long variant might regulate automatic emotional responses, which are driven by the amygdala, more efficiently, lessening their vulnerability to the framing effect.

"This one gene cannot tell the whole story, however, as it only explains about ten per cent of the variability in susceptibility to the framing effect. What determines the other 90% of variability is unclear. It is probably a mixture of people's life experience and other genetic influences.

"An interesting question would be whether the gene might affect real-life decision-making. For example, traders in banks need to make quick and accurate estimations of risk and consistent decisions, no matter how the information is presented to them. So you might hypothesise that traders with the long genetic variant would make more consistent decisions, though this needs to be tested in future research."

For more information on the story, follow the links at the top of the page.

Image: The red circles show the location of the effect in the amygdala

UCL Context

The UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience is an interdisciplinary research institute, bringing together different disciplines (such as psychology, neurology, anatomy) with common interests in the human mind and brain, in both health and disease. The institute has over 120 staff, including postdoctoral and postgraduate researchers and clinical fellows. It runs regular seminars, receives many grants for its research, and produces numerous scientific publications.

Related stories

Schizophrenia patients see through illusions: watch now

UCL study: brain activity predicts our choices

UCL research: are we as decisive as we think?

Close

Close