Q&A: Is Messina a city without memory?

14 February 2008

Last week the British Museum screened 'Messina: city without memory?' a documentary by

ucl.ac.uk/italian/staff/academicandadmin/johndickie" target="_self">Dr John Dickie (UCL Italian) about the legacy of the 1908 earthquake and tsunami that killed around one-third of the Sicilian city's 150,000 inhabitants. The film was part of a project sponsored by the Arts & Humanities Research Council to investigate the relationship between memory and place in 20th-century Italian cities. It will be shown in Messina later this year at an event to mark the centenary of the disaster.

ucl.ac.uk/italian/staff/academicandadmin/johndickie" target="_self">Dr John Dickie (UCL Italian) about the legacy of the 1908 earthquake and tsunami that killed around one-third of the Sicilian city's 150,000 inhabitants. The film was part of a project sponsored by the Arts & Humanities Research Council to investigate the relationship between memory and place in 20th-century Italian cities. It will be shown in Messina later this year at an event to mark the centenary of the disaster. A man in the film says that Messina was flourishing before the earthquake. How did the earthquake affect its development?

The idea that Messina was flourishing before the earthquake is a little bit of a myth. Its export-driven citrus fruit industry had been in difficulties for some time already because of Italy's turn to protectionism. But certainly the earthquake wiped out a great deal of entrepreneurial expertise and created an economy largely dependent on reconstruction and the state.

Did the earthquake leave an impression on the messinesi character?

That's very difficult to trace. As one of the interviewees in the film pointed out, most of the inhabitants of post-earthquake Messina were immigrants brought in from the province and from across the Straits in Calabria. And I think people in Messina have always had an awareness of the dangers of where they live. Catastrophic earthquakes punctuate the history of that part of the world, and Messina has also suffered from bombardment, plague, and other disasters throughout its long history. It is a good candidate for Italy's unluckiest city!

Given how intrinsic architectural heritage is to Italian urban centres, is the absence of visible history particularly difficult for Italians?

I think that is at the centre of what people mean when they say that Messina is a city without memory. The urban architectural heritage in so many Italian cities creates a huge burden of expectations for cities like Messina that don't fit the archetype.

Did you find that the messinesi lack a sense of local identity as a result?

I think they have a strong sense of local identity. But it is often expressed, as in some of the interviews in our film, in an elegiac key.

A young man in the film says: "Catania has more initiative because it has more historical memory". Did your experience reinforce this idea that people need to have pride in their past to fuel ambition for the future?

That's an interesting logical short-cut by the man in the first interview in our film - one I didn't have time to investigate. I'm not sure it is true that a lack of memory is in some way connected to a lack of economic initiative in Messina. It's certainly not something you'd hear from the 'history is bunk' school of capitalism! It seems truer to say that Messina's sense of its own lack of memory and identity does, at the very least, make it hard for the city to market itself.

How did you select the voices you used?

The people in the interviews were just people we happened to come across in the street or in bars. So it was just a coincidence that one of the women was studying conservation - although it would obviously have made her keener to talk to us. Many people are nervous about appearing in front of a camera. The selection was as random as we could make it in the circumstances. We also featured extended interviews with academics who have investigated various aspects of the city's history in depth, such as the cemetery. We thought their stories showed important dimensions of the broad memory issue in the city.

How did this form of research and publication differ from the more usual paper/conference format?

It takes a great deal more work! I hope the Arts & Humanities Research Council realise that, because I could have written half a book in the time it took me to produce that film! But I think it was worth it, for a number of reasons. Much of what people say is actually 'performed' through gesture and expression, etc. More of these other forms of expression make it past the editing process in the medium of film than is the case in conventional oral history. Then when you come to show the film, the audience response is much less predictable and much more enthusiastic than it is to conventional papers (many people in Messina have already seen it). It also enables you to speak to the people you are studying, and get their feedback.

You finish with "Perhaps it's time for Messina to differentiate between memory and history" . What do you mean by that?

I think 'memory' often carries with it a solemn, static and pious view of what the history of a given place is supposed to look like. Or with an unrealisable ideal of a unanimously shared common narrative. Take away those expectations from your sense of what Messina's story is about, and you get something contradictory, complex, and open to different interpretations. A history, in other words. Messina may have suffered the most lethal earthquake ever in the western world, but that does not make it uniquely cursed or anomalous, a place cut off from the broader movements of history.

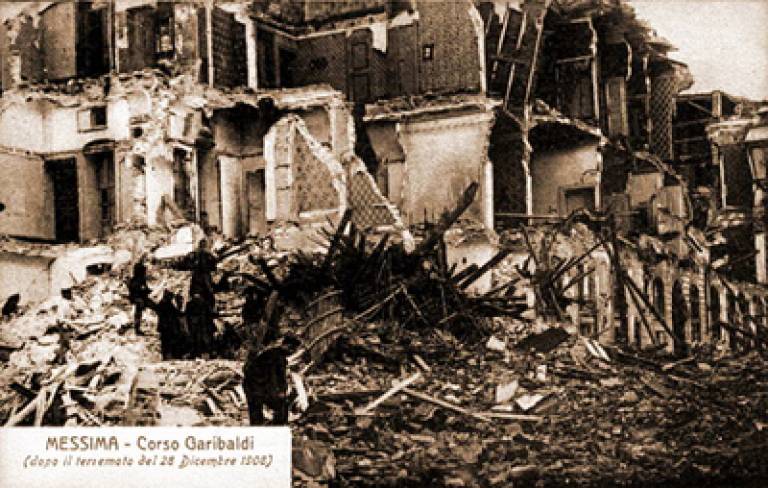

Image 1: The 1908 earthquake destroyed 90 per cent of Messina, which predated Rome. As a result, shanty towns grew up on the outskirts of the city, which are still inhabited today

Image 2: The Gran Camposanto, Messina's cemetery conceived along the lines of Rome's Pantheon, was never finished. The ruins and numerous graves of those lost in the earthquake bear witness to the disaster's indelible impact

Image 3: The Fountain of Neptune, originally housed indoors, was moved after the earthquake and tsunami to the waterfront, from where it now guards the city from the waves

Interview by Lara Carim, UCL Communications

Close

Close