Irrational decisions driven by emotions

4 August 2006

New research by two PhD students at the UCL Institute of Neurology suggests that all human decisions are affected by emotion, contradicting the old belief that man is essentially a rational creature.

'Frames, biases and rational decision-making in the human brain', published in the journal 'Science', suggests that rational behaviour may stem from an ability to override automatic emotional responses, rather than an absence of emotion altogether.

Classical economic theory has always assumed that people act rationally when taking decisions. However, it is increasingly recognised that humans often act irrationally, as a consequence of biasing influences. For example, people are strongly and consistently affected by the way in which a question is presented. A surgical operation that has 40 per cent probability of success will seem much more appealing to people than one that has a 60 per cent chance of failure.

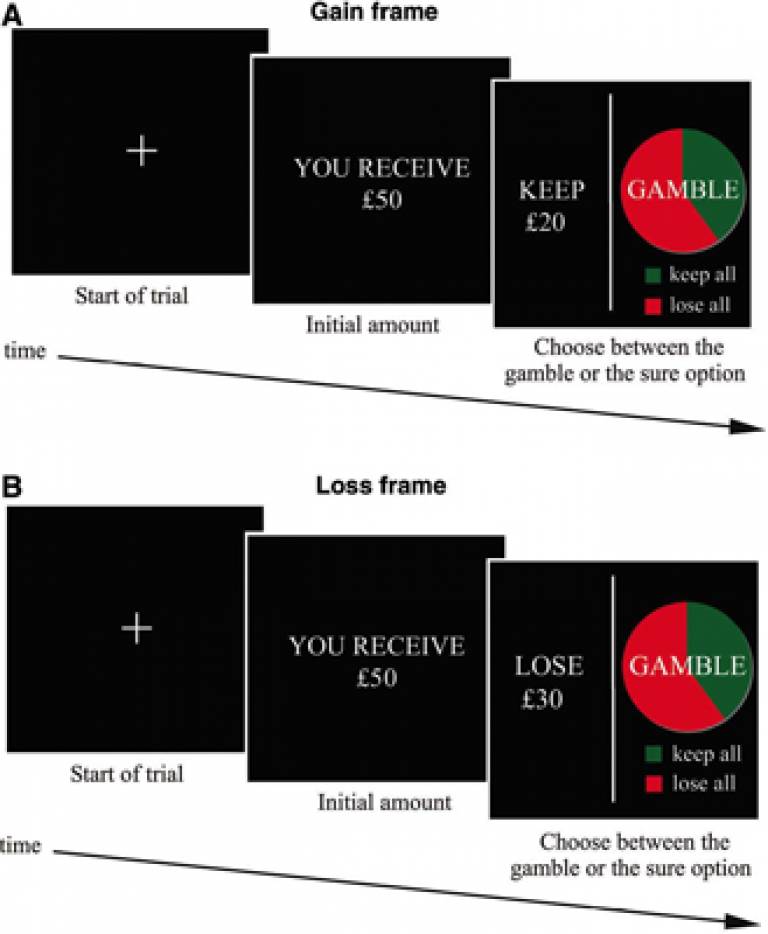

The researchers used a gambling experiment to establish the cognitive basis for rational decision-making. The goal of the task was to accumulate as much money as possible, with the incentive of being paid in real money in proportion to the money won during the experiment. Participants were given a starting amount of money (£50) at the beginning of each trial. They were then asked to choose between a sure option and a gamble option (where they would have a certain chance of winning the entire amount, but also of losing it all). Subjects were presented with these choices in two different scenarios. The sure option was worded either as the amount to be kept ('keep £20'), or the amount to be deducted ('lose £30') from the original £50. The two options, although worded differently, would result in exactly the same outcome - that the participant would be left with £20.

The study found that participants were more likely to gamble at the threat of losing £30 than the offer of keeping £20. On average, when presented with the 'keep' option, participants chose to gamble 43 per cent of the time compared with 62 per cent for the 'lose' option. Furthermore, there was a marked difference in behaviour between participants. Some people adopted a more rational approach and gambled more equally and consistently under both frames, while others showed a real aversion to risk in the 'keep' frame while at the same time displaying high risk-seeking behaviour in the 'lose' frame.

One of the researchers, Benedetto de Martino, UCL Institute of Neurology, said: "It is well known that human choices are affected by the way in which a question is phrased."

Brain imaging revealed that the amygdala, a region thought to control our emotions and mediate the 'fight or flight' reaction, underpinned this bias in the decision process.

Mr Martino added: "Our study provides neurobiological evidence that an amygdala-based emotional system underpins this biasing of human decisions. Interestingly, the amygdala was active across all participants, regardless of whether they behaved rationally or irrationally, suggesting that everyone experiences an emotional reaction when faced with such choices. However, we found that more rational individuals had greater activation in their orbitofrontal cortex (a region of prefrontal cortex) suggesting that rational individuals are able to better manage or perhaps override their emotional responses."

Image: Choices offered to participants in the gambling test

- Links:

- UCL Institute of Neurology

Close

Close