Secrets of the alchemist's lab discovered

7 May 2004

Research by UCL's Institute of Archaeology suggests that the work of 16th-century alchemists may have been more practical than magical. The research, by PhD student Mr Marcos Martinón-Torres, is the first scientific analysis of an alchemist's laboratory and demonstrates that Renaissance alchemy was a hi-tech, highly skilled science.

The Renaissance saw a massive expansion in chemical experimentation as alchemists tried to do the impossible and find the philosopher's stone and turn base metals into gold. However, partly as a consequence of these futile endeavours, new metals were discovered and equipment and techniques for metallurgical analysis were developed that are still used today.

Under the supervision of Professor Thilo Rerhren and Dr Bill Sillar, Marcos

has analysed artefacts from Castle Oberstockstall in Austria, the most comprehensive

Renaissance laboratory ever recovered.

The results show that equipment such as crucibles and scorifiers were used according to scientific principles such as the constant combining proportions and the conservation of masses indicating that alchemy was an experimental science rather than the obscure art of popular imagination. Marcos says: "This was as good as science gets for the time. We need to stop looking at them as fools, we owe them a lot."

Alchemists extensively documented their experiments, but did so in code, which until now has been difficult to decipher. By analysing the actual apparatus used, this latest research is able to provide real data which can help decode the writings. From this new perspective, "Let the diadem of the kings be of pure gold, and let the queen that is united to him in wedlock be chaste and immaculate. If you would operate by means of our bodies, take a fierce grey wolf, which is found in the valleys and mountains of the world, where he roams about savage with hunger" becomes "Let the diadem of gold be of pure gold, and let the silver that is alloyed to it be refined. If you would operate by means of our elements, take stibnite, which is found in the valleys and mountains of the world and is very aggressive."

The actual process

which is being described is the parting of gold from silver in a crucible using

stibnite. The use of 21st-century technology, such as optical microscopy scanning electron

microscopy and X-ray fluorescence, has enabled the researchers to discover the

extent of 16th-century technology. Marcos explains: "We are getting to

see what these people were actually doing for the first time, rather than what

they were writing."

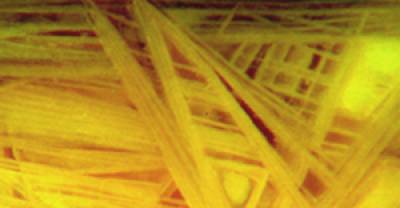

Images: Top - Two of the triangular crucibles used at the Oberstockstall laboratory. Middle - Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The Alchemist (1558). Bottom - Microstructure of the slag left in a scorifier after using it for refining gold or silver.

To find out more about the project, use the link below.

Close

Close