In 2020, Annie Cattrell was appointed as lead artist for the new facility on 256 Grays Inn Road. We caught up with Annie to find out what attracted to the project

Can you tell us about your background?

Annie Cattrell, public artist for Grays Inn Road

The museum was for medical teaching only, and there was a vast array of old preserved anatomical pathology specimens with detailed labelling telling the stories of various illnesses and diseases. The exhibits had been collected and donated to Glasgow University by the Scottish pioneering obstetrician and anatomist William Hunter (1718-1783). This opportunity profoundly affected my work and thinking and has stayed with me ever since.

Once I graduated from GSA, I undertook an MA in Fine Art at the University of Ulster in Belfast and ten years later, by then living in London, I became fascinated in the optical and conceptual possibilities and properties of glass. I was fortunate to be given scholarships to study a further MA in Glass at the Royal College of Art, where I have lectured part time since 2000. I have undertaken permanent academic positions such as Reader in Fine Art at De Montfort University, and Senior Lecturer in the Sculpture Department at the University of Gloucestershire.

Since leaving art school I have always had a studio where I draw and make mixed media three-dimensional artworks. These have been exhibited nationally and internationally in museums and art galleries, for example, recently for the Spellbound exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 2019. I have undertaken a number of large scale public art commissions for Cambridge, Bristol, Oxford Brookes, Anglia Ruskin and Oxford universities.

0 to 10,000,000 (2007. Comprising 156 coloured resin bird configurations. Oxford Biochemistry Department)

What attracted you to the public artist role at Grays Inn Road and how do you hope your work will contribute to the identity of the new building?

I was initially interested in this commission, in part, because of the location of the site above the subterranean River Fleet, and also the incredible history of the remaining buildings which originally comprised the Royal Free Hospital (RFH). The ethos and ethics of the RFH were to provide free health care for those who could not afford it, and this still seems increasingly pertinent, given the challenges facing the NHS right now with Covid-19.

My approach for the public art commission for the current design phase of the new facility at Grays Inn Road is to try to embody these principles, and to bring an awareness and understanding of what will happen within the new buildings to the fore. The development will house world leading researchers, nurses, academics, clinicians and surgeons who will use highly sophisticated technological equipment for the treatment of the patients. It is this finely tuned symbiotic relationship between the patients and staff that really fascinates me in this preliminary stage. There is a huge motivation to develop and improve health care and to more deeply understand the complexities and challenges that Alzheimer’s, Multiple Sclerosis, Huntington’s, Parkinson’s, Motor Neurone, Stroke and Epilepsy present to us all.

The new buildings will offer beautiful bespoke spaces that help to encourage collaboration and are inspirational to work in and inspirational for the patients and public to visit through time. I have begun online discussions with IoN, UK DRI and UCLH staff about their work and research, plus what they find inspirational and aspirational in terms of how paradigm shifts could potentially happen at Grays Inn Road. It is my aim to subtly embed this vision and intensity, through sculptural means, into the new bespoke spaces, therefore creating meaningful artworks that will enhance and amplify the identity of this emotionally charged environment for years to come.

What themes do you explore in your work?

As a multidisciplinary visual artist my focus is informed by acts of paying attention, noticing, contemplating and watching. At times, it seems almost forensic. I am drawn to symmetries, discrepancies and inaccuracies that allow me to see how structures, patterns or new understandings can emerge both conceptually and physically. Part of this process involves observing subtle topographical changes in, for example, the landscape, or atmospheric fluctuations and weather conditions, or more intimately inside the human body and brain.

This noticing is partly aimed at capturing the fleeting and what is not obviously visible, highlighting the almost imperceptible changes, flux and transformations that are ceaselessly occurring inside the human body and in the natural world. This sculptural arresting or pause is designed to allow for in-depth scrutiny and reflection to occur through time and in three dimensions. As part of this approach and process I often use visual sequences and comparative series to highlight the visible changes and behaviour of the materiality of what constitutes life.

Conditions (2007. 12 optical subsurface etched glass blocks that reflect average cloud formations in and around London from January to December. Each block 400mm x 150mm x 150mm. Commissioned for the Out of the Ordinary exhibition at the V&A in London)

What medium and materials do you work with?

I draw, take photographs and film as a way of recording, ‘thinking aloud’ and making ‘visual notes’. Additionally, I gather relevant written information, collect materials and research that form a compendium to record ideas and develop connections. In my studio I cast, assemble, fuse, weld and etch using techniques in bronze, glass, wood and many other appropriate materials. This creative process connects the ideas into a form and/or a structure. New digital approaches have also led me to explore and use state-of-the-art technologies, for example forming topographical Lydar laser data into rapid prototype SLA models. This 3D virtual modelling has also proved invaluable when developing ideas with architects such as Hawkins Brown for public art projects.

How do you view the relationship between art and neuroscience?

For me, the relationship that connects art and neuroscience lies in the commonalities of approach in terms of creativity and experimentation. Discursive, imaginative and lateral thinking seems to be vital to both specialisms. My practice has been informed by working with specialists in neuroscience, psychiatry and the history of science. I have always been particularly interested in the parallels and connections that can be drawn within and between the disciplines of art and science.

However, I do think the intentions and resolutions are very different indeed. Scientists are trying to prove or discount their theory or hypothesis. Whereas artists, generally, do not want to be bounded by convention and the rational.

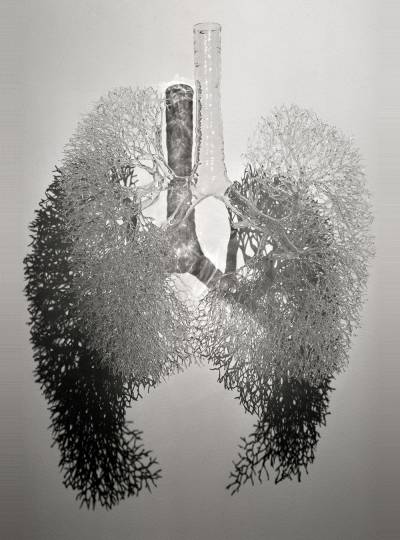

Capacity (2001. Glass and acrylic. 600mm x 450mm x 300mm, edition of 3)

To what extent do you think art can help people understand or relate to neuroscience research?

It is difficult to determine if and how art can help people relate to neuroscientific research. I am reminded of an art/research project that might help begin to convey how I have previously worked with neuroscientists and neurosurgeons and how this was disseminated through a public exhibition.

In 2011, I was commissioned to make a new body of work for a group exhibition called Coming of Age for the Hancock Museum (Great North Eastern Museums) in Newcastle. I worked at the Institute of Ageing, part of Newcastle University, and became interested in the three dimensional anatomy of the Hippocampus and Amygdala (as seen in autopsies and in MRI/CT scanning techniques). Both form part of the Limbic system - a set of structures that support the functions of emotion and memory (Latin translation of Limbic = border or edge). In discussion with neuroscientists there, I found out that the Hippocampus can be damaged as a result of the onset of Alzheimer’s and therefore this small section of the brain is crucial to the overall wellbeing of the effected person. Some of the symptoms of the damage can be loss of memory and disorientation in the patient’s behaviour.

I used three-dimensional anatomical data from within the brain and outer scans of the surface of the brain/skull to reveal the shape, orientation and volumes of these crucial physiological brain areas. The sculptural works were called Memory (I and II) and referenced the deep physical location of where memories are stored within the brain and also how our identity can be altered through the onset of Alzheimer’s.

Also relevant to this commission was a previous experience of being given permission to watch neurosurgeon Mr Henry Marsh undertake an ‘awake craniotomy’ procedure at the Atkinson Morley Wing at St George’s Hospital in London. This was in 2002, and was a pioneering surgical technique to remove tumours close to or involving the speech regions of the brain. During the operation the patient is woken up and the anaesthetist speaks with them continuously while they are awake, allowing the team to test regions of the exposed brain throughout the procedure to check the patient’s speech function in relationship to the removal of diseased brain tissue. Mr Marsh encouraged me to look down the microscope he used to view into the patients brain. As I did this he said: “thought is physical”.

0 to 10,000,000 (2007. Comprising 156 coloured resin bird configurations. Oxford Biochemistry Department)

What role do you think art can play in society more broadly?

Art can stimulate debate, make connections, challenge existing ideas and inspire those who experience it. It can also act as a focus and axis from which to more fully understand the cultural and political history of a particular place. More specifically, sculpture can also afford three-dimensional possibilities to ‘activate’ a given space through its conceptualisation, composition, physicality and material properties.

“Art can stimulate debate, make connections, challenge existing ideas and inspire those who experience it

Can you tell us a bit about your creative process and what inspires your work?

I have always engaged in immersive experiences that cannot be ‘switched off’, which are in essence 360 degrees, such as climbing mountains or watching brain surgery. It is the phenomenological observations I can make while in these situations of the place, space, sounds, textures, smells etc that influence decision making later in the studio. Often in the countryside or in specific environments I find this can amplify my awareness and expand and transform sensation into ideas, thoughts into artworks.

One example of this way of working and approach was when I was on Orkney in 2010, undertaking a Royal Scottish Academy residency hosted by the Pier Art Centre. Daily, I was able to observe, film and draw the tidal and wave energy of the surrounding sea, particularly the Pentland Firth that separates the north of mainland Scotland and Orkney. So I was observing deep time, as visible in the coastal geology at the precipitous Jesnaby cliffs, and then discussing renewal energy developments and challenges with research scientists at Herriot Watt University at their campus in Stromness. This process of the conjoining of a theoretical understanding of the surrounds and site visits to observe time made for thought provoking combinations, then and now.

SEER (2018. Situated on the banks of the River Ness in Inverness. Casts taken directly from the distinct geologies at the Great Glen Fault, where two tectonic plates meet, either side of Loch Ness. Resin with a metal armature)

In other completed artworks such as Echo (2007), Fault (2018) and SEER (2018) I embed geological time, by casting directly from specific geological locations in England and Scotland. With Echo this was from a quarry of Pennant sandstone, in the Forest of Dean, which was formed during the Carboniferous period about 350,000,000 years ago when it was part of the Supercontinent of Pangaea situated near the equator. This deep geological time is physically evident in the cast, in the layered rigid structures of the rock and impermanence of the trees, pine needles and earth.

Fault and SEER were also cast, this time directly from either side of Loch Ness. On each side of the loch are distinct land regions called the North West Highlands and Grampian Mountains that were formed from two tectonic plates converging and forming Loch Ness. James Hutton (1726–1797), the “father of modern geology,” wrote the Theory of the Earth (published in 1788) that proposed the idea of a rock cycle in which weathered rocks form new sediments and that granites were of volcanic origin. At Glen Tilt in the Cairngorm Mountains, near to Loch Ness, he found granite penetrating metamorphic schists - this proved that granite was formed from the cooling of molten rock. As a result of this observation regarding geological time scales Hutton famously remarked: “that we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.”

ECHO (2007, Park of the Forest of Dean Sculpture Park, Resin with a metal armature)

What are your plans over the coming months for the Grays Inn Road public art programme?

Since mid-April I have begun to have online dialogues with the UCL Culture Team and engage with UCLH staff and future stakeholders of Grays Inn Road. Through this design stage period, I have started to develop my ideas and approaches and I also hope to meet people face to face and go on site as soon as possible. My plans are, in part, being determined by the current lockdown situation and I look forward to making progress and plans of this project visible as soon as possible!

Close

Close