A new type of leg implant for young cancer patients

14 December 2014

Biomedical engineers have developed an implant to lengthen limbs in young patients with bone cancers. It reduces the number of invasive surgeries patients require, cutting the risk of complications. Not only has patients' health and quality of life improved, but the implants have also been a commercial success for Stanmore Implants.

Each year in the United Kingdom, approximately 50 children with bone cancers require surgery to save their affected limb, with the bone replaced by an implant able to be lengthened periodically to keep pace with growth in the healthy limb. Invasive extendible implants were first developed in the 1970s, but these required repeated surgical procedures as the child grew and had a high risk of complications, including joint stiffness and nerve injury.

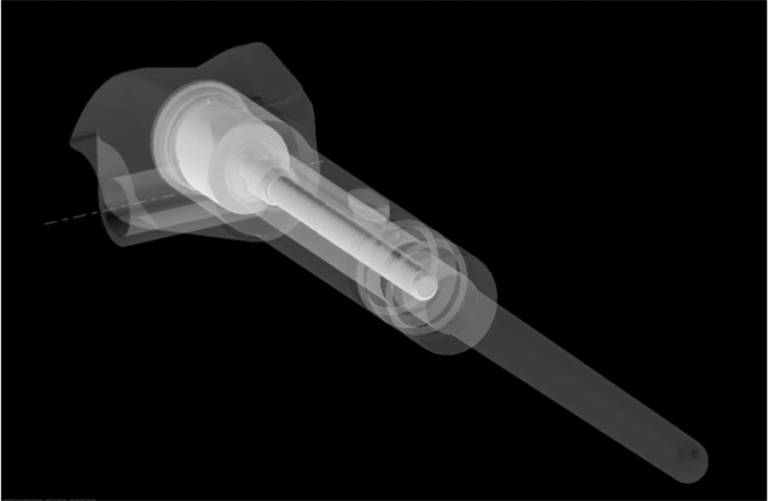

To overcome these challenges, UCL's Professor Gordon Blunn produced a prosthesis that could be lengthened within the body without the need for extensive surgery. His team of researchers developed an implant, based on an electric motor along with a super magnet and a gearbox, all contained within the implant.

The prosthesis can be lengthened in a quick and pain-free procedure conducted at an outpatient clinic - cutting the number of expensive and invasive surgeries the children require. As a result, it reduces the risk of infection and subsequent treatment, as well as reducing the costs of bone reconstruction and growing by around £19,000 per patient. After being inserted, the prostheses can be extended more gradually than more invasive alternatives, reducing nerve palsies, stiffness and pain for patients.

Compared to other similar prostheses on the market, the Stanmore implant scores higher on a range of categories - including pain, walking quality and patient satisfaction. It also has a much lower failure rate than rival devices: in one clinical trial of an alternative device, seven of 15 implants had mechanical failure. In comparison, of 55 children who underwent reconstruction with the UCL prosthesis, 10 of the 11 patients who were skeletally mature at the end of the study had equal leg lengths and nine had a full range of movement of the hip and knee. Such is the superiority of the UCL design, in fact, that a number have been used to replace failed competitor implants.

Since 2008, the Stanmore implant has been the standard UK treatment for children with these bone cancers, although some minimally invasive devices are still used. After the initial implant surgery, no anaesthesia is required for the lengthening process. The device also has wider applications than for paediatric patients: 1-2% of the implants have been used to treat skeletally mature patients with shortening after failed joint replacement surgery.

The implant has not only been an improvement for the young patients requiring surgery. Since a full UK and US patent was granted in 2001, more than 400 devices have been sold and used in 15 countries around the world, generating over £6 million income for UCL spinout company Stanmore Implants Ltd. In 2011, the device received FDA approval for use in the USA.

Close

Close