Hip replacements: Changes to health policy and regulation

16 December 2014

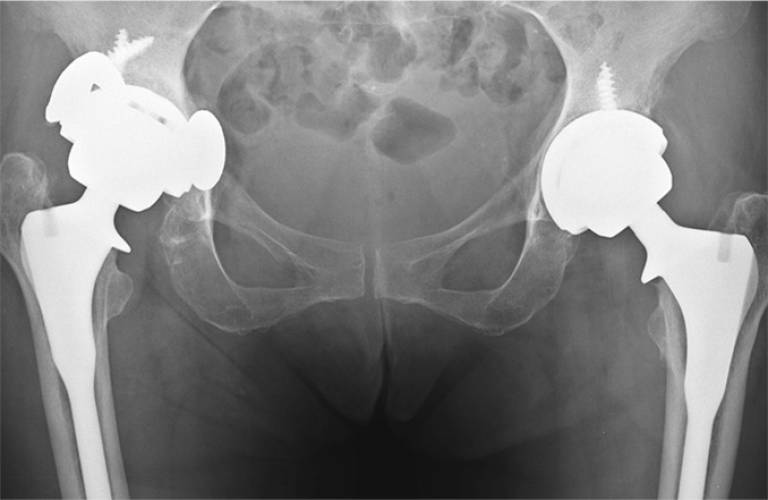

Patients around the world with metal-on-metal (MOM) hip replacements have benefited from UCL research that identified major problems with the implants. Health regulators have made changes to the use and regulation of the devices, while replacement surgery has improved patients' quality of life.

MOM hips were found to release small amount of metal into patients' bloodstream, which could cause tissue damage. Techniques developed through the research have revolutionised the management of patients with metal-producing hips. For instance, the researchers identified the cut-off level for metal ions in patients' blood between poor and well-functioning hips. They also developed an award-winning MRI protocol - MARS MRI - that more easily detects soft tissue inflammation and muscle damage adjacent to metal implants. Both these tests were unavailable in all NHS hospitals in 2006 and are now routine.

The blood metal ion cut-off level (of 7 parts per billion) has informed clinical guidance disseminated around the world. It was first adopted by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in 2010, at which point there were around 90,000 patients with MOM hips in the UK. NICE (the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) updated its recommendations for hip replacement surgery in February 2014, issuing stricter guidelines that rule out the use of most types of MOM implant in the UK. International health regulatory agencies and professional bodies, including the US Food and Drugs Administration, Australian Therapeutic Goods Association and American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons have used the research to create their own recommendations affecting many of the 1.5 million patients worldwide that have MOM hips.

A failed implant is like a black box of an aircraft. It holds vital information that can help understand why it failed. - Professor Alister Hart

A global programme to retrieve MOM implants and replace them with better-performing devices has been instituted. Surgeons from 22 countries have removed 6,000 components from 3,000 patients since 2008 and sent them to UCL for analysis. Evidence from the research has been used to support patient claims against the manufacturers of these faulty implants and a number of manufacturers have recalled hips.

The research has also influenced a change in the regulation of all metal-on-metal hip devices in the United States and United Kingdom, with greater scrutiny of all orthopaedic implants before devices are approved for use: never again should there be a medical implant disaster of the scale seen as a result of MOM hips.

Another crucial result has been to improve the quality of life of patients suffering from painful hip replacements. Patients who experience an adverse reaction to a MOM hip now have them replaced with a ceramic-based implant, after which levels of metal ions in the patient's blood rapidly fall. By identifying some of the factors that can predict if a patient will have problems with a MOM hip, such as hip size, and the patient's age and sex, the research has led to a reduction in the number of patients receiving these hips and thus being at risk of complications.

The research was conducted in collaboration between UCL, Imperial College London and the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital, Stanmore.

Close

Close