The benefits of painting analysis for conservation and our cultural heritage

12 December 2014

Using specialist techniques to examine paint materials, Libby Sheldon has made possible the accurate dating of Old Master and British paintings. Her analysis has contributed to professional and public understanding and enriched appreciation of technical art history.

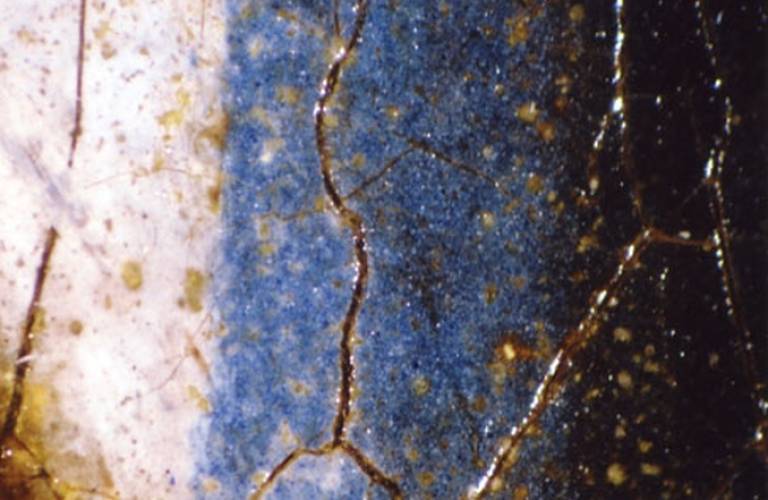

Sheldon (formerly UCL History of Art), is recognised as the leading paint analyst working in the UK and a pioneer of technical art history. In 2005 she made an important research breakthrough by establishing the authenticity of a painting by Vermeer in a private collection, previously thought to be a fake or a 19th-century pastiche. She used new imaging techniques to map the presence of mineral pigments and paint combinations known to be used by Vermeer.

Her research into pigments used in 16th-17th century British portraiture underpins the analysis of important works in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), including interpretations of specific works. For example, her analysis of a Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I by an unknown artist (c.1575) enabled original paint palettes to be determined, highlighting the vulnerability of certain pigments to colour change with age and opening possibilities for new interpretations of the works. The analysis of paint samples from Elizabeth I, Darnley portrait, where she identified discoloured blue and red pigments and showed that the orange raised patterning over the costume was originally purple, were used by the NPG to enable viewers to have a fuller sense of what the paintings would have looked like when painted: in this case of a richer, more colourful image of the Virgin Queen than we see today.

Sheldon's research contributed to/ played a key role in the authentication and dating of painted works of art, and facilitated a deeper understanding of artistic production methods and the trade of mineral pigments, as well as robust identification of fakes and forgeries. Her exploration of the history and technology of pigments has led her to raise questions about artists' intentions and viewers' perceptual skills. For example, using microscopic techniques and comparing a large sample of Old Master paintings from the Making Art in Tudor Britain project at the NPG, she investigated whether subtle 16th and 17th century combing and texturing techniques were aesthetic effects or deliberately practical strategies to manage the oil medium. Through an associated exhibition, website and public lectures by Sheldon, new developments within technical art history were brought to public attention, contributing a unique picture of the material life of paintings.

Working at the interface between art history and heritage science, Sheldon's investigations and microscopic analyses of the Victorian painter Sir John Gilbert shed new light on this once famous artist. Her analysis of his extraordinary uses of gouache and watercolour mediums on ten paintings at the Guildhall Art Gallery in 2009-10 demonstrated not only an adventurous use of new pigments but also, of aqueous media in unprecedented large-scale formats. This discovery for what had previously thought to be oil paintings, had important implications for their care and conservation, and contributed to a renewed appreciation of this painter.

Sheldon contributed to another dramatic re-evaluation when she showed that the Portrait of Olivia Boteler Porter found in the storeroom of the Bowes Museum, Country Durham, was by Van Dyck, and elevated it to become one of the treasures of this national collection.

Sheldon's art historical 'detective work' has attracted widespread public interest. An appearance on the BBC's Culture Show was viewed by 1.5 million people, and brought coverage in the national press. She has also appeared on popular programmes such as Fake or Fortune?, discussing her analysis on of the painting to an audience of 4.8 million viewers.

Image

- A microphotograph shows the ultramarine blue of a chair in the Vermeer painting Young Woman Seated at a Virginal. The attribution to Vermeer was largely a result of the finding of ultramarine in the painting by the Painting Analysis unit. Research into the use of ultramarine by other 17th century artists showed that Vermeer was distinctive in both the manner of handling it, and the very good quality of the ultramarine pigment used. Image courtesy Libby Sheldon.

Close

Close