The Isles of Scilly

Graveyard of West-Indiamen

a guest blog by Nigel Pocock

Scilly, a group of tiny islands off the tip of Cornwall, is en route from the Caribbean to London. Here is was that at least fifty, and probably many more, West-Indiamen, Guineamen, slave ships - call them what you will - were wrecked, foundered, lost, declared derelict, 'a-shored' by the locals for every conceivable item that could used in their homes as consumables or furniture, or sold on. These vessels had been trading in slave-produced products, indigo, cotton, rice, tobacco, sugar, cocoa, and rum, and enslaved Africans.

Tryumph, 1736

After a stormy crossing of the Atlantic from Jamaica with sugar, rum, and indigo, known slaver William Crosse and his drunken crew, hit the Steval Rock, Isles of Scilly. Carrying the modern equivalent of millions in cash, this was not an area known for wrecks. What had Crosse and his crew been trading in that was so lucrative? Slaves? Given his track record, this must be almost certain. Unfortunately none lived to tell the tale.

We know that William Crosse was on the slaver Cardigan in 1724, and that his colleague, Ignatius White, was on the slaver John Galley (or Johns Galley) in 1710. In the case of William Crosse's voyage on the Cardigan, he was planning to embark 600 slaves from Ouidah (Whydah, Benin) in his 310-ton vessel, for the South Sea Company, to Jamaica. This was not slaving on a small scale.

[insert image View of the Steval Rock, off the Garrison, St Marys]

Scipio, 1758

Sailing from Jamaica, this 250 ton ship carried eight carriage guns and eight swivel guns (for quelling insurrections), the captain and first mate were John Cappes and John Watson, with a crew of about forty. They also carried a Letter of Marque (due to the Seven Years War, 1756-63), unusual amongst slaving ships. Two years earlier this vessel went to the Cape Coast and Gold Coast, embarking 386 enslaved Africans, of which 334 arrived in Kingston, Jamaica. Wrecked at an unknown site in Scilly, only part of the rum was saved, all the crew perished.

One of the owners of this venture was the well-known slaver, Vincent Briscoe, related through his wife to the Duke of Somerset. Briscoe was in league with important Bristol slavers James Laroche and Richard Farr, in connection with Thomas Elsworthy (or Elworthy), captain of the slaver Jamaica Pacquet.

[insert image View of the Steval Rock, off the Garrison, St Marys]

William, 1800

While research shows that the William (master, William Ellison or Elliston) was not actually wrecked (in the sense that she was declared 'derelict'), she was almost definitely a slaver. Sailing from 'Martinico' (Martinique) to Scilly, she was said to be 'on shore' and 'feared will be lost'. Evidently she was not 'lost', as she was still in existence in 1801. Of the captain, William Ellison, there is no doubt of his slaving credentials. On this voyage he had been taking around 350 enslaved Africans from Cape Coast Castle, Gold Coast and Cape Coast, to either St. Vincent or Martinique (or both), of which 303 slaves arrived. The vessel was either registered in Spain, or was a prize from the Spanish. She was 'wrecked' on Scilly on 17th January, 1800. The owners were the well-known slavers, Calvert & Co, of London.

Governor Milne, 1806

The most bizarre story I have found to date must be that of the Governor Milne, an undoubted slaver, a tale of grossly incompetent opportunism and deviousness. In 1806 the Governor Milne was an elderly, 24 year old Quebec-built (1792) vessel of 178 tons. She was copper sheathed for tropical waters, a prime requirement of slave ships, with long waits, and therefore exposure to the dreaded attacks of the toredo worm. Several slave captains had been in charge of her, including Captains David Neale (1799) and Thomas Boland (1799), and (possibly) Caleb Greene (1803). David Neale was intending to embark 206 slaves, but his voyage (1799) was scuppered before it had even begun. Stranded on the sands off Whitstable after only 9 days out, she was deserted by the crew, until towed off. Neale had made a previous slaving voyage on the Camelion (1798) and was to make another on the Roebuck (1800).

Thomas Boland was a slave captain between 1800-6, but only his first slaving voyage in the 11-year old New Providence-built Charlotte (1800) appears to have been successful. After this he was clearly a very expensive liability, perhaps also sailing rather dodgy vessels. The Charlotte was abandoned during a second voyage (1801) or condemned as unseaworthy. Boland then set forth on the slaver Dart (1804) out of Liverpool, which was shipwrecked or destroyed. He had earlier tried the slaver Diligence (1803), owned by Anthony Calvert, which was then captured by the French. His last recorded voyage, by which time even Boland himself might have realised that he was not up to the job, was on the slaver President Ince (1806), which was shipwrecked or destroyed. It is interesting that a Hugh Boland also made a slaving voyage around the same time (Britannia, 1803). He, too, was shipwrecked or destroyed.

When the rudderless Governor Milne was wrecked in Scilly in 1806 she was under the command of a Captain Moffatt, about whom nothing is known. She was en route from Grenada to London with sugar. This was unloaded. The vessel was then condemned as unseaworthy, but not before she had drifted from St. Mary's to Tresco. However, in 1807 the Governor Milne was plying between St. Domingo and London. Was she 'repaired' after the insurance money had been pocketed?

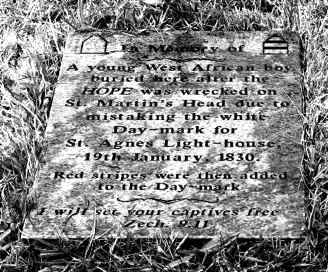

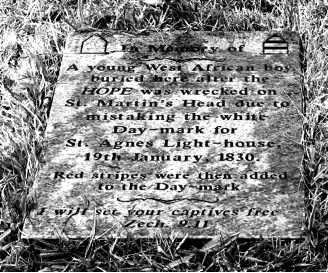

Hope, 1830

The brig Hope is notable because we know there was a 'black boy' aboard. He was buried in St. Martin's Churchyard, where there is a memorial to him. The story of the Hope follows the claim that the ships' captain, Alfred or Champion Noble (accounts differ), mistook the day-mark on St. Martin's for the light-house on St. Agnes, on completely the opposite side of the islands. Both are of similar height, shape, and (at this time) both were painted white. The Hope then ran onto St. Martin's Head in the ensuing gale. As a result the young black boy, together with a Dutch officer from Elmina Fort and his wife, were all drowned when the main mast fell on them as they were attempting an escape.

In addition to the stories of enslaved Africans connected to the Atlantic waters there are several recorded cases of Black people in Scilly. For example in 1712, 'a Negro' was lost from the Gallaway, master Smith, from St. Kitt's to London, wrecked on Seven Stones Reef. Was this a sailor, or a 'privilege Negro' given to a slaver as a bonus in addition to his slave trading, that he could sell on his return to London? Around 1773, a 'Negro female' was saved from the Felicity, from St. Domingo that ran around on St. Mary's. What had this African girl, likely to be between 6-15 years old, been through on board? The Nancy Packet (1784), records the presence of an African nanny, and the sinking of the Susan, master Miner, that struck Seven Stones in 1827, reveals the story of a black man who could not swim, and so refused to leave the boat, and drowned, in spite of a rescuing Tresco pilot boat in the area.

Further reading

Marcus Rediker, 2007, The Slave Ship: A Human History, London, John Murray

Sources for the work in Scilly are very varied, but central are the Trans-Atlantic Slave Database, CUP (CD-Rom or on-line); the National Archives, Newspapers, Lloyd's Registers & Lloyd's Lists (at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich). On Scilly, I am especially indebted to maritime historians Richard & Bridget Larn for their pioneering data collection on wrecks.

Nigel Pocock is Director of Vision Training & Research and an On-line Parish Clerk for Wiltshire. He had been visiting Scilly for many years when he noticed the huge number of vessels carrying slave-produced cargoes in the records which had clearly never been examined. He is currently working on the stories of Leonora Casey Carr, an Antiguan slave who was manumitted, and attended the Moravian School in East Tytherton, Wiltshire, together with the sisters, Ann, Sarah, Eliza, and Alicia Briggs, the first three also slaves from Antigua.

Close

Close