Black Victorians in Melbourne Gaol

Caroline Bressey

When its bluestone walls were erected between 1852 and 1864 Melbourne Gaol dominated the developing skyline. Designed to emulate the 'model prison' plans of the British engineer Joshua Jebb, particularly Pentonville Prison in London, the Gaol's narrow cells and walkways enjoy little natural light even on a bright summer day. A short walk from the formal Carlton Gardens the Gaol is now dwarfed by the tall blocks of modern Melbourne, its former Hospital Compound and Wardmen's Yard (1865 - 1925) an alumni courtyard for nearby RMIT University. Consistently overcrowded the Gaol was closed in 1929. As a popular tourist attraction the Old Melbourne Gaol now retells the sorry tales of hopeful migrants, the marginalised poor and displaced Aborigines.

Like Victorian prisons in Britain, both Melbourne Gaol and Pentridge Prison (1850-1997, Coburg, north Melbourne) took photographs of their male and female prisoners. These images have been collated into five albums dating from between 1878 and 1897. Now held in the Public Record Office Victoria, the albums provide a glimpse into some of the lives of black people who lived in Melbourne - men (so far I've not found any women) from Africa, Britain and the United States. The images usually include an individual's prison number and with this it is possible to trace them in the archived prison registers. These written records include physical descriptions of the men; tattoos, scars, the colour of their eyes; details of their crime; their profession; the ship on which they arrived in Australia.

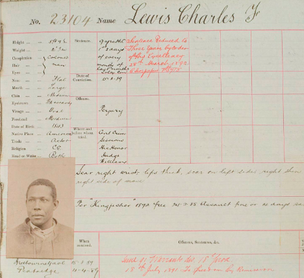

Charles Lewis Jr was an actor from the United States who arrived in Australia on the Kingfisher in 1872 - 17 years before entering the prison system for perjury. Born in 1843 Lewis stood over 5ft 9inches and could both read and write. Had he been born enslaved or free? Had he managed to survive as an actor for nearly two decades? A report of a packed out performance of 'The Octoroon' in the Melbourne Argus of September 1878 mentions a Mr Charles Lewis in the role of Captain Ratts - an early Australian review? Received at Melbourne Gaol on 15 March 1889, Lewis arrived at Pentridge Prison the following month. Although he served less than the 3 years of his original sentence the photo taken on his release gives a sense of how that time in prison aged him.

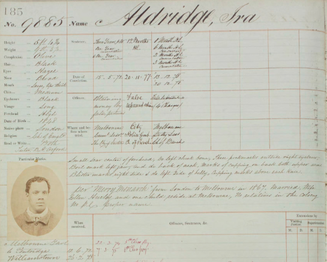

Born in London in 1848 Ira Aldridge was imprisoned three times for fraud. Although a fraudster his name is said to be his 'proper one' but it is intriguing for it is also the name of the pioneering African-American actor who made his name on the stages of Britain and Europe. The actor Ira Aldridge was born in New York in 1807. As a young man he joined the African Theatre amateur group set up by New York's free African-American community. Following the forced closure of the collective in 1823 Aldridge headed to Britain. In 1825 he made his first appearance on the London stage at the Royal Coburg Theatre now the Old Vic near London's Waterloo. Here he played the role of Oroonoko in the Revolt of Surinam or Slave's Revenge. In 1833 he played Othello at the Covent Garden Theatre but his performance faced racist reviews from the London critics. The extent of their racism resulted in future performances being cancelled.

Although Aldridge's performance of Othello gained respect from critics outside London, in 1852 Aldridge left England to tour mainland Europe where his celebrated performances were seen in many cities including Brussels, Cologne, Berlin, Dresden, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Munich and St Petersburg. Eventually acknowledged by the London critics Aldridge continued to tour in Europe, travelling to Odessa and Istanbul and he died while on tour in Europe in 1867 - the same year the Ira Aldridge in the Melbourne prison archive arrived in the Australian Colony of Victoria.

What was the relation between this prisoner and his namesake - was the name and the story of his former life in London all part of his 'con man' identity? The prison record states that Aldridge arrived in Australia on the Merri Monarch in 1867 and was married to Ellen Huxley with whom he had one child. There is an I D Aldridge on the passenger list for the Merri Monarch in 1867 and a marriage certificate which records than on 10 January 1868 Ira Daniel Aldridge married Ellen Huxley at the Registrar's office in Fitzroy, Melbourne. Ellen, a seamstress and the daughter of a carpenter, was also born in London and it is possible that the pair knew each other before they arrived. The marriage certificate also gives Ira's father's name as: Ira Frederick Aldridge, Profession: actor. His mother is listed as Margaret Gill, Ira Adridge's first wife. Daniel was the name of Ira's African-American grandfather, so it would seem to be confirmed that the eldest son of this pioneering actor entered the Melbourne prison system more than once.

Announcements in The Argus indicate that Aldridge intended to follow his father into a career on the stage when he first arrived in Melbourne, but by the time he married Ira worked as a tutor. The couple had their first child Mary in 1869, but she died after just one day. In 1870 their first son Ira Frederick was born, two years before his father's first conviction in May 1872. Between Ira's convictions he and Ellen continued family life. James Ira was born in 1873 (although he died at 10 months), followed by John Edward in 1875 and Arthur Henry born in 1878 who died after only 4 months. He seems to be their last child together. As neither of them have been traced in the death records of Victoria it is also possible that they moved on to another part of Australia in order to start a new life once again.

What of their two surviving children? John Edward is still to be traced. Ira Frederick died aged 24 on the way to the hospital on Gipps Street, East Melbourne (now the site of St Vincents & Mercy Private Hospital). His death certificate records that he was married but the name of his wife was unknown. He was buried in an unmarked plot in Melbourne General Cemetery on 24 May 1894. The grave covered with dry twigs and gravel lies along a narrow dusty path in the pauper's section of the cemetery. The grave is shared with two other Victorians, their intertwined resting place a quiet memorial to the complex historical geographies of the black British presence in colonial Australia.

Between December 2011 and February 2012 Caroline Bressey will research the histories of the Black British presence in Australia as a Visiting Scholar at Monash University, Melbourne.

References

Peter Fryer, Staying Power: the history of black people in Britain, Pluto Press 1984.

Herbert Marshall and Mildred Stock, Ira Aldridge: The Negro Tragedian, Howard University Press 1993.

Old Melbourne Gaol National Trust of Australia, Victoria.

Close

Close