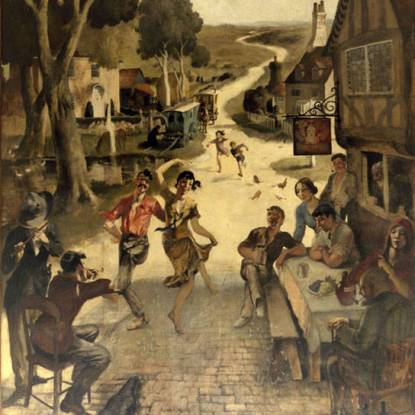

The Four Founders of UCL

Henry Tonks, The Four Founders of University College London, 1922, oil on canvas LDUCS-5723

Location: UCL Flaxman Gallery

Mural by a Slade professor to celebrate UCL's centenary. Depicting a fictional meeting between Jeremy Bentham, Lord Brougham, Thomas Campbell, Henry Crabb Robinson and the architect to discuss Wilkins Building plans.

Painted in commemoration of the centenary of the London University this group portrait of the Four Founders of University College with the architect William Wilkins – who is also famous for designing the National Gallery – was completed in 1923.

It was designed to be placed in the drum of the dome of the main College building and shows the principal figures associated with the founding of the University of London (later University College London). Kneeling at the right is the architect William Wilkins who presents his plans of the building to Jeremy Bentham , standing in the centre of the composition, and the poet Thomas Campbell who first conceived the idea of a London University. At the left stand Lord Brougham, lawyer, politician and Benthamite, and behind him the diarist, former Times correspondent and retired barrister Henry Crabb Robinson who was instrumental in establishing the Flaxman Gallery.

In choosing to place Jeremy Bentham at the centre of this work, Tonks perpetuated the myth of Bentham as one of the founding fathers of UCL. It is true that Campbell, Brougham, Crabb Robinson and others were strongly influenced by Bentham and his belief that education should be open to anyone regardless of their religion. When it was founded, UCL was referred to as the ‘Godless College of Gower Street’. Bentham was 80 by the time teaching began at the University, and, while he gave the venture his backing, he contributed little else to the actual founding of UCL.

The Artist at work

Tonks used an expensive canvas, and a medium of oil colours mixed with white wax and turpentine. He sometimes worked on the painting for 8 to 9 hours a day.

He shows the classical building rising in the background, still ensconced in scaffolding. As for the portrait of Jeremy Bentham, Tonks had no need to study any contemporary portraits of Bentham, as the original was available for reference in the University itself (see The AutoIcon).

In a letter to A.M. Daniel dated July 1922, Tonks wrote:

“Sometimes I think I have done a fair performance, at other times I flush all over thinking I have made an absolute ass of myself, certainly I did when I saw it suspended in the air on its way up the scaffolding to its final resting-place, merely however, put there for the moment to test it, it being then taken down to go on with. I found out what it wanted. A decoration must be anyhow of this nature, very complete, no vague passages, as monumental, almost as statuesque, as possible. At the same time, as one’s natural study all one’s life has been to produce a unity of lighting, that has to be well kept up. I shall be very interested to show it to you, being certain, not that you will like it, but that you will take pains to find out its qualities, and I have taken enormous pains, however silly it is. I want it to be in its place when the walls are finished being painted, because I do (notwithstanding your prayer) want to do the whole dome, and I should like to get authorities interested. I want to encourage decoration and the only way is, to do it. It is no good talking about it. It will be splendid practice for the students. Of course, faces are not so easy. I have been studying Rubens in connection with them.

The perspective is designed specifically for this location where it is to be viewed from below. “My assistant,” wrote Tonks, “was admirable doing all the bits I hate doing such as working out the perspective of the architecture. I mixed the tones, and we hit off at one shot just the right ones for the architecture.”

The picture seems to have retained a place in his affections until the end; after his retirement from the Slade he frequently corresponded with his successor, Professor Schwabe, about its condition. The work was damaged in a bomb blast during WWII and after its restoration it was hung at the north end of the North Cloisters of the Wilkins building. It was returned here to its original location in 1986.

Henry Tonks (1862 – 1937)

Son of a Solihull foundry owner, Henry Tonks (1862 – 1937) began his medical studies at the Royal Sussex County Hospital in Brighton, transferring to the London Hospital to complete his studies in 1881. Tonks had always been interested in drawing, and had briefly attended a local art school while a student in Brighton. During his time at the London Hospital, a demonstrator of anatomy fell ill and Tonks was asked to replace him. This post allowed him to use and develop his skills as a draughtsman, making demonstration drawings and diagrams for his students. Tonks qualified as a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in January 1886 and two months later became House Surgeon at the London Hospital, later moving to the Royal Free Hospital. He became a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in June 1888.

In the same year as he achieved this medical distinction he began to attend classes at the Westminster School of Art under Frederick Brown, and spent much of his free time drawing there. Tonks began exhibiting his work at the New English Art Club in 1891. In 1892 Brown was appointed Slade Professor and offered Tonks the post of assistant which he accepted, leaving medicine behind him for good.

Tonks was celebrated on his death as ‘the greatest leader of that great revival of the art of drawing.’ Although the Slade had placed life drawing at the centre of the curriculum from its foundation in 1871, and two previous Slade Professors – Edward Poynter and Alphonse Legros – had instituted the Slade tradition of linear constructive drawing on which Tonks built, Tonks was the teacher who became most closely associated with Slade drawing.

Close

Close