What protects killer immune cells from harming themselves?

27 November 2019

White blood cells, which release a toxic potion of proteins to kill cancerous and virus-infected cells, are protected from any harm by the physical properties of their cell envelopes, find scientists from UCL and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne.

Until now, it has been a mystery to scientists how these white blood cells – called cytotoxic lymphocytes – avoid being killed by their own actions and the discovery could help explain why some tumours are more resistant than others to recently developed cancer immunotherapies.

The research, published in Nature Communications, highlights the role of the physical properties of the white blood cell envelope, namely the molecular order and electric charge, in providing such protection.

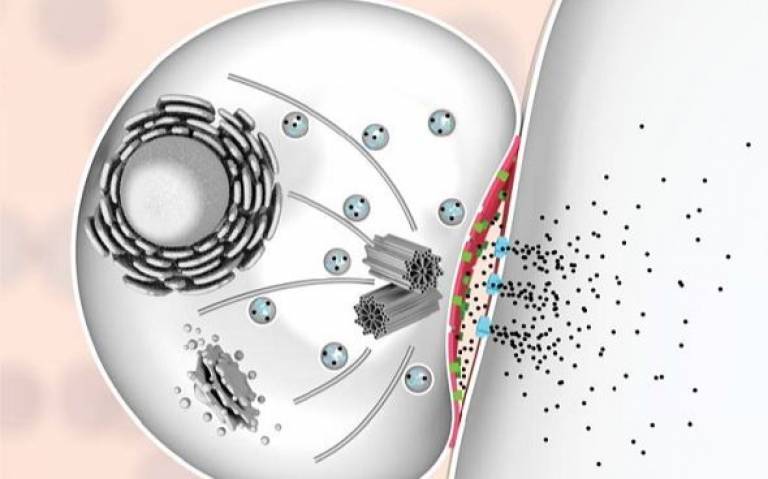

According to Professor Bart Hoogenboom (London Centre for Nanotechnology, UCL Physics & Astronomy and UCL Structural & Molecular Biology), co-author of the study: “Cytotoxic lymphocytes, or white blood cells, rid the body of disease by punching holes in rogue cells and by injecting poisonous enzymes inside. Remarkably, they can do this many times in a row, without harming themselves. We now know what effectively prevents these white blood cells from committing suicide every time they kill one of their targets.”

The scientists made the discovery by studying perforin, which is the protein responsible for the hole-punching. They found that perforin’s attachment to the cell surface strongly depends on the order and packing of the molecules – so-called lipids – in the membrane that surrounds and protects the white blood cells.

More order and tighter packing of the lipid molecules led to less perforin binding, and when they artificially disrupted the order of this lipid in the white blood cells, the cells became more sensitive to perforin.

However, they also found that when the white blood cells were exposed to so much perforin that some of it stuck to their surface, the bound perforin still failed to kill the white blood cells, indicating that there must be another layer of protection. This turned out to be the negative charge of some lipid molecules sent to the cell surface, which bound the remaining perforin and blocked it from damaging the cell.

Joint first author, Dr Adrian Hodel, who screened and studied many membrane systems for this work, said: “We have long known that local lipid order can change how cells communicate which each other, but it was rather surprising that the precise physical membrane properties can also provide such an important layer of protection against molecular hole-punchers.”

In Melbourne, joint first author Jesse Rudd-Schmidt, who focused on the characterisation of the white blood cells in Associate-Professor Ilia Voskoboinik’s laboratory, said: “What we have found helps to explain how our immune system can be so effective in killing rogue cells. We are now also keen to investigate if cancer cells may use similar protection to avoid being killed by immune cells, which would then explain some of the large variability in patient response to cancer immunotherapies.”

The work was kindly funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, and by the Sackler Foundation.

Links

- Full paper in Nature Communications

- Professor Bart Hoogenboom’s academic profile

- London Centre for Nanotechnology

- UCL Physics & Astronomy

- UCL Mathematical & Physical Sciences

- UCL Structural & Molecular Biology

- UCL Life Sciences

- UCL Institute for the Physics of Living Systems

Image

Schematic of a white blood cell attached to the surface of a cancer cell, punching holes (light blue) in the cancer cell surface to facilitate entrance of poisonous enzymes (black dots). The white blood cell itself is protected against the hole punchers by the order and charge of its membrane (red), which allows it to survive the encounter unharmed.

Close

Close